Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

CodeOCR: حول فعالية نماذج الرؤية واللغة في فهم التعليمات البرمجية

CodeOCR: حول فعالية نماذج الرؤية واللغة في فهم التعليمات البرمجية

Yuling Shi Chaoxiang Xie Zhensu Sun Yeheng Chen Chenxu Zhang Longfei Yun Chengcheng Wan Hongyu Zhang David Lo Xiaodong Gu

الملخص

حققت النماذج اللغوية الكبيرة (LLMs) نجاحًا ملحوظًا في فهم الشفرة المصدرية، ومع ذلك، مع تزايد حجم الأنظمة البرمجية، أصبحت الكفاءة الحسابية عقبة حرجة. تعتمد هذه النماذج حاليًا على منهجية قائمة على النص، حيث تُعامل الشفرة المصدرية كسلسلة خطية من الرموز (tokens)، ما يؤدي إلى زيادة خطية في طول السياق والتكاليف الحسابية المرتبطة به. ويُتيح التقدم السريع في النماذج اللغوية متعددة الوسائط (MLLMs) فرصة لتحسين الكفاءة من خلال تمثيل الشفرة المصدرية كصور معروضة بصريًا. على عكس النص، الذي يصعب ضغطه دون فقدان المعنى الدلالي، فإن الوسيط البصري مناسب بشكل طبيعي للضغط. من خلال تعديل الدقة، يمكن تقليل حجم الصور إلى جزء ضئيل من تكلفة الرموز الأصلية مع الحفاظ على قابليتها للتعرف من قبل النماذج القادرة على الرؤية. ولدراسة جدوى هذا النهج، أجرينا أول دراسة منهجية حول فعالية MLLMs في فهم الشفرة المصدرية. تُظهر تجاربنا أن: (1) يمكن لـ MLLMs فهم الشفرة بشكل فعّال مع تقليل كبير في عدد الرموز، ما يُمكن من ضغط يصل إلى 8 أضعاف؛ (2) يمكن لـ MLLMs الاستفادة الفعالة من المؤشرات البصرية مثل تظليل بناء الجملة، مما يُحسّن أداء إكمال الشفرة تحت ضغط 4 أضعاف؛ و(3) تُظهر مهام فهم الشفرة مثل الكشف عن التكرار (clone detection) مقاومة استثنائية للضغط البصري، حيث تُظهر بعض نسب الضغط أداءً أفضل قليلاً من المدخلات النصية الأصلية. تُبرز نتائجنا كلًا من الإمكانات والقيود الحالية لـ MLLMs في فهم الشفرة، مما يشير إلى تحوّل نحو تمثيل الشفرة باستخدام الوسيط البصري كممر نحو استدلال أكثر كفاءة.

One-sentence Summary

Researchers from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Singapore Management University, and others propose using Multimodal LLMs to process source code as compressed images, achieving up to 8× token reduction while preserving performance, leveraging visual cues like syntax highlighting for efficient code understanding and clone detection.

Key Contributions

- LLMs face efficiency bottlenecks with growing codebases due to linear token growth; this work pioneers using rendered code images as a compressible alternative, enabling up to 8× token reduction while preserving semantic understanding.

- Multimodal LLMs effectively exploit visual features like syntax highlighting, boosting code completion accuracy under 4× compression, demonstrating that visual cues enhance performance beyond raw text inputs.

- Code clone detection tasks show strong resilience to image compression, with some ratios outperforming raw text inputs, validating image-based representation as a viable, efficient pathway for scalable code understanding.

Introduction

The authors leverage multimodal large language models (MLLMs) to explore representing source code as images rather than text, aiming to reduce computational costs as codebases grow. Traditional LLMs treat code as linear token sequences, making compression lossy and inefficient; prior work lacks systematic evaluation of code images despite MLLMs’ visual capabilities. Their main contribution is a comprehensive empirical study showing that MLLMs can understand code images effectively—even at up to 8x compression—with some tasks like clone detection outperforming text baselines. They also introduce CODEOCR, a tool for rendering code into compressible, visually enhanced images, and identify model-specific resilience patterns and optimal rendering strategies.

Dataset

The authors use a curated set of four benchmark tasks to evaluate visual code understanding, each targeting different comprehension levels and processed with specific metrics and context handling:

-

Code Completion:

Uses 200 Python and 200 Java samples from LongCodeCompletion (Guo et al., 2023), drawn from a challenging subset (Shi et al., 2025a). Applies RAG to inject relevant code context (avg. 6,139 tokens for Python, 5,654 for Java). Evaluated via Exact Match and Edit Similarity. -

Code Summarization:

Leverages LongModule-Summarization (Bogomolov et al., 2024), with 109 samples averaging 6,184 tokens. Uses CompScore — an LLM-as-judge metric via DeepSeek-V3.2 — with bidirectional averaging for fairness (scores 0–100). -

Code Clone Detection:

Draws from GPT-CloneBench (Alam et al., 2023), focusing on Type-4 semantic clones. Samples 200 balanced pairs (100 positive, 100 negative) per language (Python avg. 125 tokens, Java avg. 216 tokens). Evaluated via Accuracy and F1. -

Code Question Answering:

Constructs a new 200-sample dataset to avoid leakage in LongCodeQA (Rando et al., 2025). Crawls 35 post-August-2025 GitHub repos, generates 1,000 candidate QA pairs via DeepSeek-V3.2, then filters via 3 PhD validators ensuring question validity, context necessity, and unambiguous correctness. Final set shuffled to remove positional bias. Evaluated via Accuracy.

All token lengths are computed using Qwen-3-VL’s tokenizer. The datasets are used to probe code understanding across languages, with Python as primary and Java for extended analysis.

Method

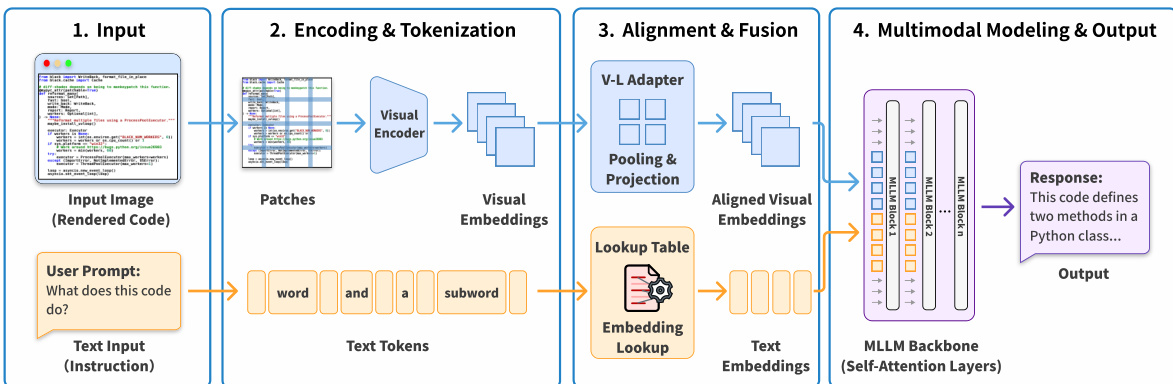

The authors leverage a multimodal pipeline to enable large language models to process source code as visual input, bypassing traditional text tokenization. The framework begins with rendering source code into high-resolution images—2240×2240 pixels by default—to ensure compatibility with common patch-based visual encoders. This resolution allows for clean division into fixed-size patches (e.g., 14×14 pixels) without partial tiles, preserving visual fidelity during tokenization. The rendered image, which may include syntax highlighting or bold styling for enhanced visual cues, is then processed alongside a text-based instruction prompt.

Refer to the framework diagram, which illustrates the four-stage processing pipeline. In Stage 1, the input consists of a rendered code image I∈RH×W×3 and a natural language instruction. Stage 2 involves encoding: the image is split into patches, and a Vision Transformer encoder generates a sequence of visual embeddings V=Encoder(I)={v1,v2,…,vN}, where each vi represents a patch’s visual features. Simultaneously, the text prompt is tokenized into subword units and mapped to text embeddings via a lookup table.

In Stage 3, alignment and fusion occur. A V-L Adapter applies pooling operations—such as 2×2 patch merging—to compress adjacent visual embeddings into denser representations. For example, a pooling operation combines four patches via concatenation and an MLP projection:

Tv=MLP(Concat(vi,i,vi+1,i,vi,i+1,vi+1,i+1))This reduces the visual token count while preserving semantic structure. The aligned visual embeddings are then concatenated with the text embeddings to form a unified input sequence:

Input=[Tv;Ttext]Stage 4 involves the MLLM backbone, typically composed of self-attention layers, which processes the fused sequence to generate a response. Unlike text-only models that rely on discrete syntax, MLLMs interpret continuous visual patterns—such as indentation, bracket alignment, and color coding—directly from pixel data, enabling spatial reasoning over code structure.

To optimize cost and efficiency, the authors introduce dynamic resolution compression. Starting from the high-resolution base image, they apply bilinear downsampling to achieve target compression ratios (1×, 2×, 4×, 8×), where the visual token count is reduced to 1/k of the original text token count. This allows users to trade visual fidelity for token savings while maintaining performance on downstream tasks.

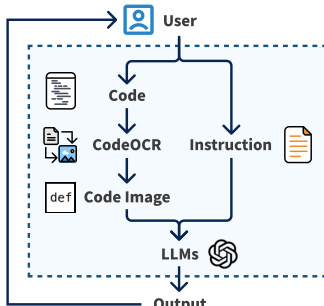

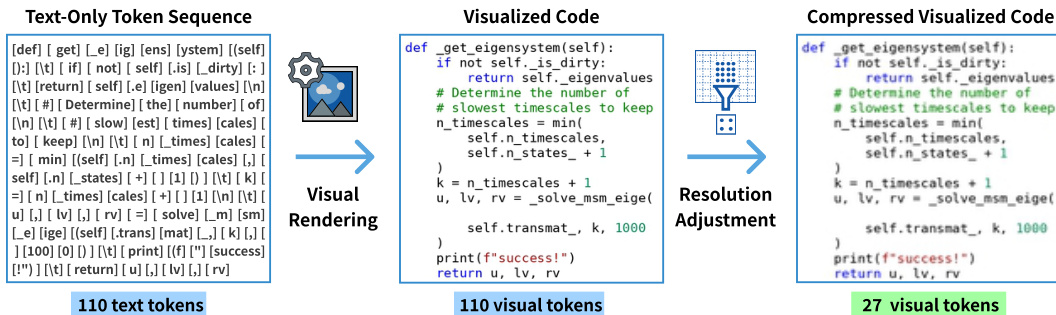

The CODEOCR middleware operationalizes this pipeline. As shown in the workflow diagram, users supply code and instructions; CODEOCR renders the code into a syntax-highlighted image and dynamically compresses it to meet specified token budgets. The resulting image is passed to the MLLM alongside the text instruction, and the model’s output is returned to the user. Internally, CODEOCR uses Pygments for syntax analysis and Pillow for rendering, supporting six core languages with extensibility to 500+ via Pygments’ lexer ecosystem.

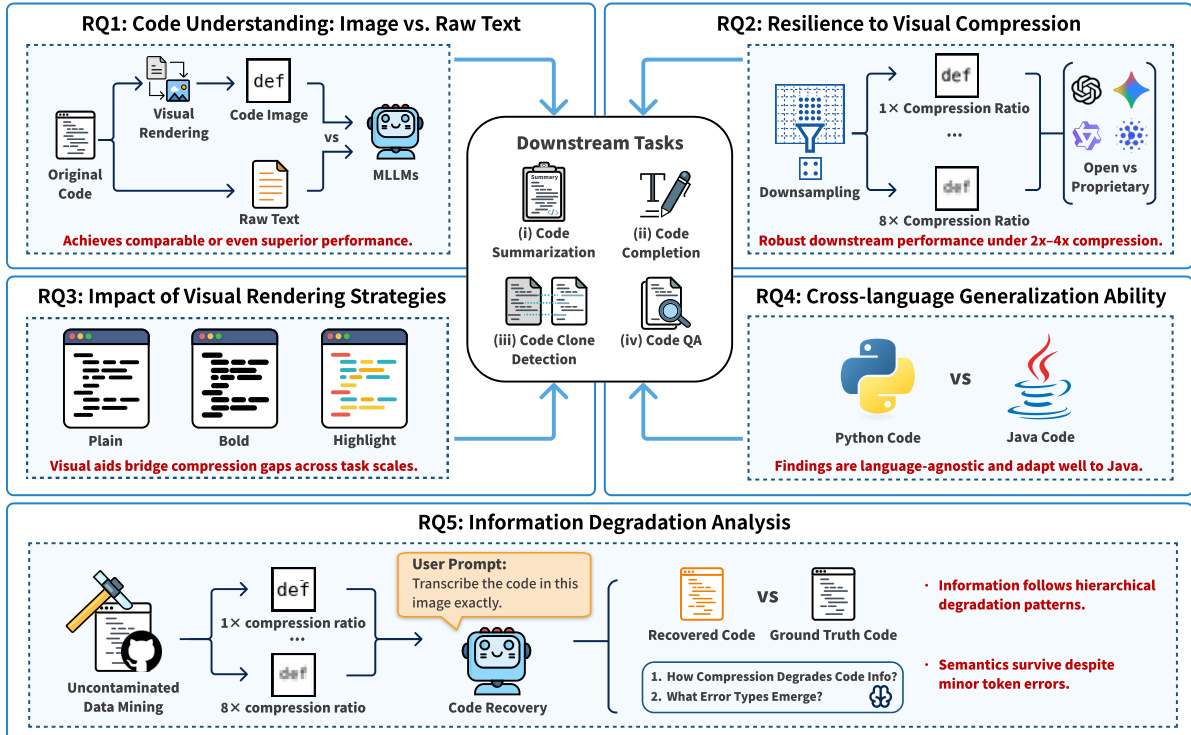

The empirical design, depicted in the study overview, evaluates five research questions across four downstream tasks: code summarization, completion, clone detection, and question answering. The authors compare visual code input against raw text baselines, assess resilience to compression, evaluate rendering strategies (plain, bold, highlighted), test cross-language generalization, and analyze information degradation under compression. This systematic evaluation confirms that visual code representation not only matches but often exceeds text-based performance, particularly under compression, and adapts robustly across programming languages.

The visual rendering and compression process is further illustrated in the transformation diagram, which shows how 110 text tokens are converted into 110 visual tokens via rendering, then compressed to 27 visual tokens through resolution adjustment—enabling significant token savings without sacrificing task performance.

This architecture enables MLLMs to treat code as a visual artifact, unlocking new modalities for structured content representation while maintaining compatibility with existing text-based instruction paradigms.

Experiment

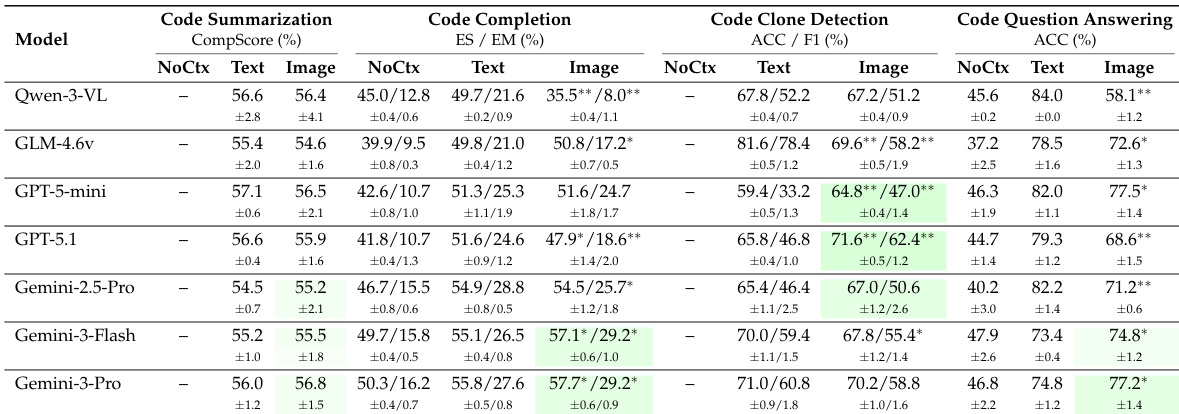

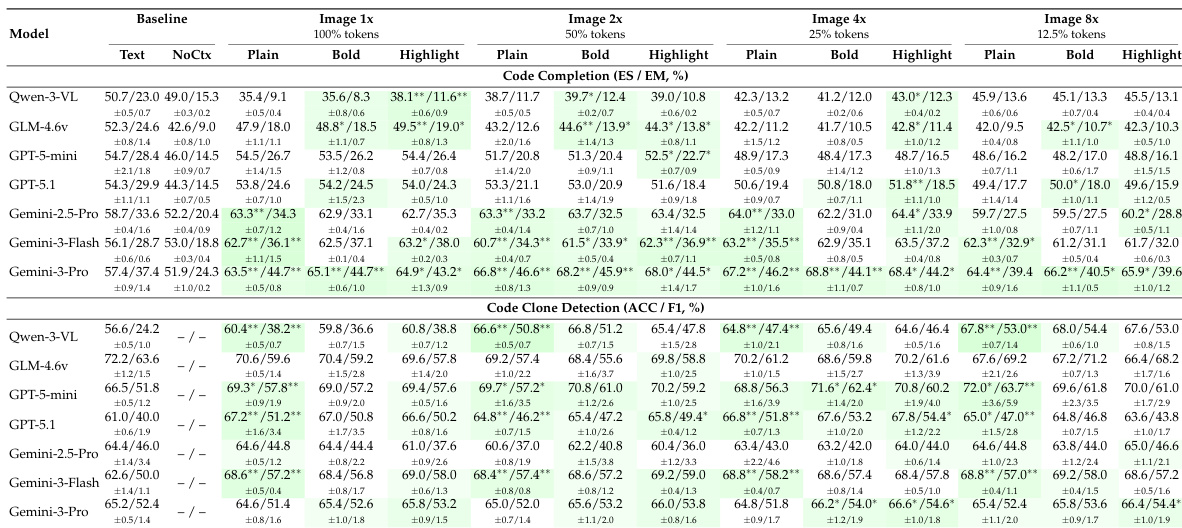

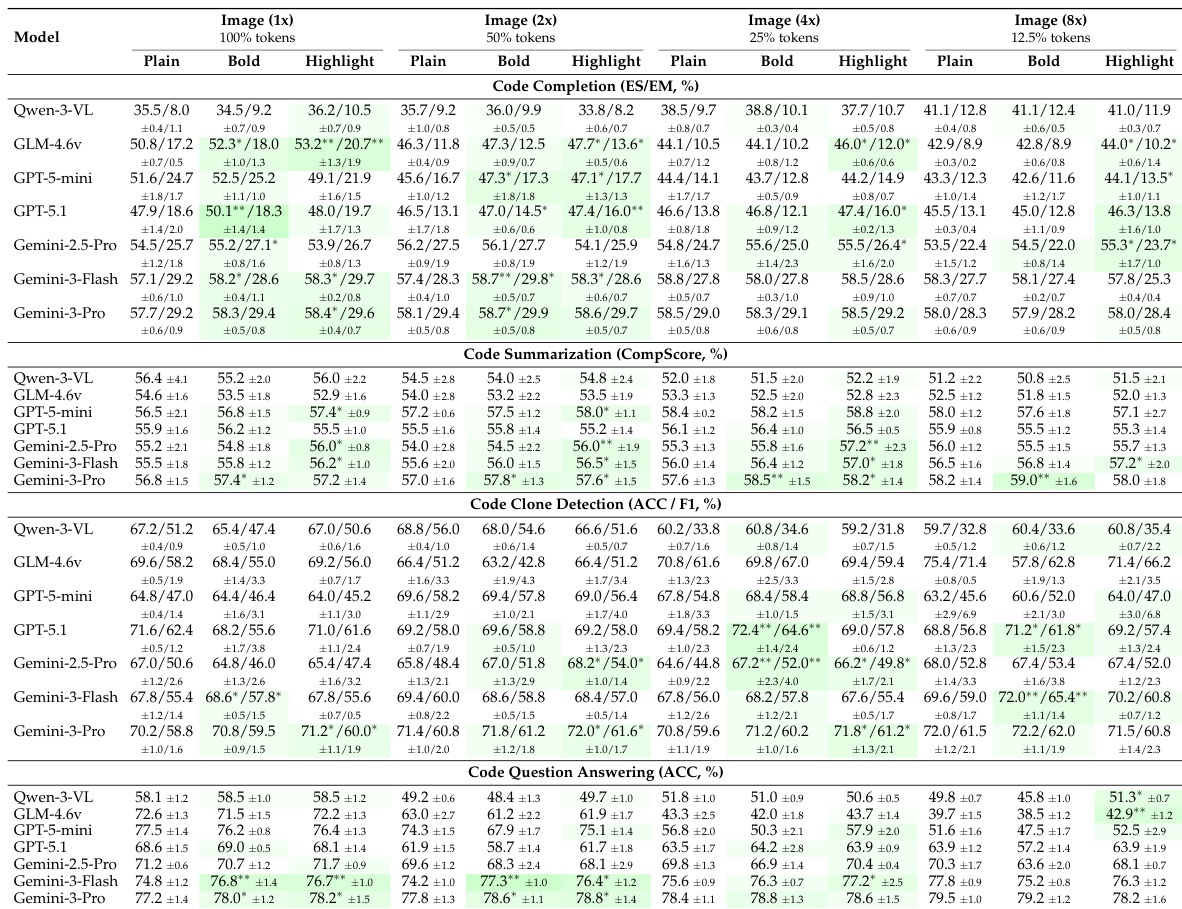

- LLMs can effectively understand code images, matching or surpassing text-based performance in key tasks like clone detection and code completion, especially with models like Gemini-3-Pro and GPT-5.1.

- Visual compression (up to 8x) is tolerated well in summarization and clone detection, but code completion and QA degrade beyond 2x–4x for most models, except top-tier ones like Gemini-3-Pro which improve under compression.

- Syntax highlighting and bold rendering enhance code image understanding significantly at low-to-moderate compression (1x–4x), particularly for advanced models, but offer diminishing returns at high compression.

- Findings generalize across programming languages—core patterns in performance, compression resilience, and enhancement benefits hold for Java as well as Python.

- Compression degrades code information hierarchically: token errors appear first, line errors emerge at moderate compression, and block errors dominate at high compression; Gemini-3 models maintain low block error rates, explaining their consistent downstream performance.

- Visual code processing introduces negligible latency overhead compared to text, enabling practical deployment with potential speedups via compression.

Results show that large language models can effectively understand code presented as images, with some models achieving comparable or better performance than text-based input across multiple programming tasks. Performance varies significantly by model and task, with state-of-the-art models like Gemini-3-Pro demonstrating strong resilience to visual compression and benefiting from syntax highlighting or bold rendering, while weaker models often degrade under compression. The findings generalize across programming languages, and visual code processing introduces minimal latency overhead, supporting practical deployment.

The authors evaluate seven multimodal LLMs on code understanding tasks using visual inputs at varying compression levels and rendering styles. Results show that visual code representations can match or exceed text-based performance, especially for tasks like clone detection and summarization, with stronger models like Gemini-3-Pro maintaining robustness even at high compression. Visual enhancements such as syntax highlighting and bold rendering improve performance at moderate compression but offer diminishing returns at extreme levels.

Results show that large language models can effectively understand code presented as images, with some models achieving comparable or superior performance to text-based input across multiple programming tasks. Performance varies significantly by model and task, with Gemini-3-Pro demonstrating consistent strength in both raw and compressed visual inputs, while open-weight models like Qwen-3-VL and GLM-4.6v show notable degradation under visual or compressed conditions. Visual enhancements such as syntax highlighting and bold rendering improve performance at moderate compression levels, but their benefits diminish at higher compression ratios where image clarity is reduced.