Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

اكتشاف رياضيات شبه تلقائي باستخدام جيميني: دراسة حالة حول مسائل إردوش

اكتشاف رياضيات شبه تلقائي باستخدام جيميني: دراسة حالة حول مسائل إردوش

الملخص

نقدم دراسة حالة في اكتشاف رياضي شبه ذاتي، باستخدام نموذج جيميني (Gemini) لتقييم منهجي لـ 700 افتراض تم وضع علامة "مفتوح" عليها في قاعدة بيانات مشاكل إردوش لبloom. نستخدم منهجية هجينة: التحقق من خلال اللغة الطبيعية المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي لتضييق نطاق البحث، تليها تقييم من قبل خبراء بشريين لتحديد صحة الافتراضات وحداثتها. وقد تم التعامل مع 13 مشكلة كانت مُعلّمة بـ "مفتوح" في القاعدة: خمسة منها عبر حلول تلقائية تبدو مبتكرة، وثمانية أخرى عبر تحديد وجود حلول سابقة في الأدبيات المتوفرة. تشير نتائجنا إلى أن حالة "المفتوح" لهذه المسائل ناتجة عن التضليل أو التغيب عن الأنظار، وليس عن صعوبتها الفعلية. كما نحدد ونناقش التحديات الناشئة عن تطبيق الذكاء الاصطناعي على الافتراضات الرياضية على نطاق واسع، مع التأكيد على صعوبة التعرف على الأدبيات السابقة، وخطر ما يمكن تسميته "الاقتباس غير الواعي" (subconscious plagiarism) من قِبل الذكاء الاصطناعي. ونُلخّص الاستنتاجات المستخلصة من الجهود المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي في سياق مشاكل إردوش.

One-sentence Summary

Researchers from Google and collaborators propose using Gemini to evaluate 700 open math conjectures, resolving 13 via novel AI solutions or rediscovered literature, revealing that “open” status often reflects obscurity, not difficulty, while cautioning against AI’s risk of subconscious plagiarism in large-scale mathematical discovery.

Key Contributions

- We applied Gemini to evaluate 700 'Open' conjectures from Bloom’s Erdős Problems database using a hybrid AI-human workflow, narrowing the search via natural language verification before expert validation, and resolved 13 problems—5 with novel autonomous solutions and 8 by rediscovering prior literature.

- Our results indicate that the 'Open' status of these problems often stems from obscurity rather than intrinsic difficulty, as AI efficiently surfaced overlooked or trivially resolved conjectures, challenging assumptions about problem hardness in the database.

- We document key challenges in scaling AI for mathematical discovery, including the difficulty of comprehensive literature retrieval and the risk of AI inadvertently reproducing known results without attribution, which we term “subconscious plagiarism.”

Introduction

The authors leverage Gemini to evaluate 700 “Open” conjectures from Bloom’s Erdős Problems database, using AI-driven natural language verification to filter candidates before human expert review. This approach matters because it scales AI-assisted discovery in math, where expert evaluation is bottlenecked by time and scarcity. Prior work faced challenges in reliably verifying correctness at scale and identifying whether solutions already existed in the literature — often leading to redundant or misleading claims. The authors’ main contribution is resolving 13 problems: 5 with seemingly novel autonomous solutions and 8 by uncovering prior literature, revealing that many “open” problems were simply obscure, not hard. They also highlight systemic issues like AI’s risk of subconscious plagiarism and the difficulty of literature retrieval — problems formal verification cannot solve.

Method

The authors leverage a geometric incidence framework to establish a lower bound on the growth rate of αk, defined as the minimal number of distinct distances determined by any point in a set of n points in the plane. The core of the method involves constructing a family of circles derived from a carefully selected subset of k points and then applying a known incidence bound to derive a contradiction unless αk grows at least as fast as k1/4.

The construction begins by selecting a set Pn={x1,…,xn}⊂R2 ordered such that R(xi), the number of distinct distances from xi to other points in Pn, is non-decreasing. The first k points, S={x1,…,xk}, are used to define a family of circles C=⋃i=1k{Γ(xi,r):r∈Di}, where Di is the set of distinct distances from xi to the rest of Pn. Since each ∣Di∣<αkn1/2, the total number of circles satisfies ∣C∣<kαkn1/2.

The key insight is that every point p∈Pn∖S lies on at least k circles in C, one for each center in S. This yields a lower bound on the number of incidences between Pn and C: (n−k)k. Applying the Pach–Sharir incidence bound (Theorem 1) with k=3 and s=2 for circles, the upper bound on incidences becomes c(3,2)(n3/5∣C∣4/5+n+∣C∣). Substituting the bound on ∣C∣ and taking the limit as n→∞ yields k≤C(αk4/5k4/5+1), which implies αk=Ω(k1/4).

This method hinges on the interplay between geometric construction and combinatorial incidence bounds, transforming a problem about distance distributions into one about curve-point incidences, and then leveraging asymptotic analysis to extract the desired growth rate.

Experiment

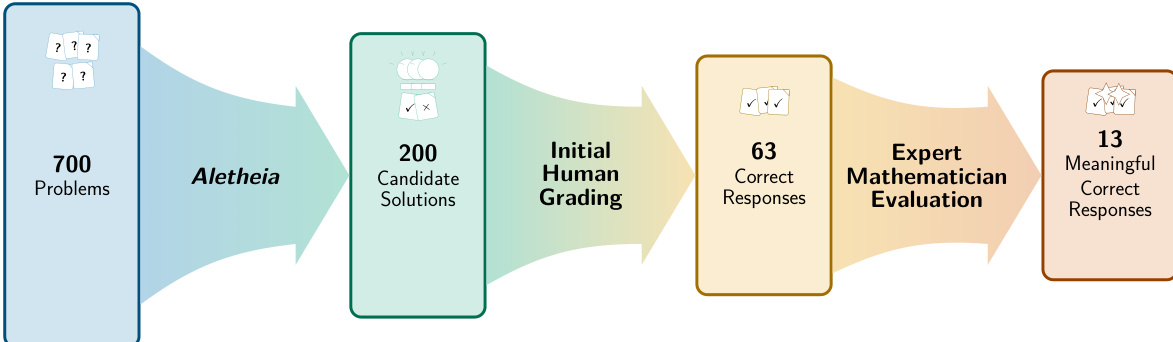

- Aletheia, a math research agent built on Gemini Deep Think, evaluated 700 open Erdős problems, yielding 63 technically correct solutions, but only 13 meaningfully addressed Erdős’s intended problem statements; 50 correct solutions were mathematically trivial due to misinterpretation, and 12 were ambiguous.

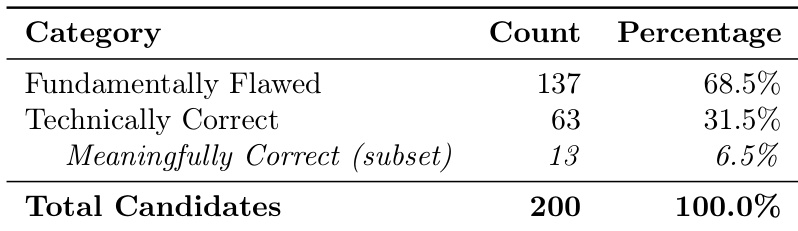

- Human evaluation revealed that 68.5% of 200 graded responses were fundamentally flawed, highlighting the high cost of verifying AI output, including debugging errors and checking for literature overlap or unintentional plagiarism.

- Among 13 meaningfully correct solutions, 5 were autonomously novel (Erdős-652, 654, 935, 1040, 1051), though none rose to the level of a standalone research paper; Erdős-1051 was later expanded into a collaborative paper.

- Aletheia also identified 8 problems already solved in the literature (e.g., Erdős-333, 591, 705), and rediscovered 3 solutions independently (e.g., Erdős-397, 659, 1089), raising concerns about subconscious plagiarism from training data.

- Final validation revealed that some “solved” problems had flawed or ambiguous formulations, such as Erdős-75, where the listed problem was a misstatement of Erdős’s original intent, underscoring the need for precise problem framing in AI-driven research.

- The effort emphasizes that while AI can assist in mathematical discovery, its outputs require rigorous human vetting, and claims of “accelerating science” must account for the hidden labor of verification and contextual accuracy.

The authors used a specialized AI agent to generate solutions for 700 open Erdős problems, then evaluated 200 candidate responses with human mathematicians. Results show that while 31.5% of responses were technically correct, only 6.5% meaningfully addressed the intended mathematical problem, highlighting the gap between syntactic correctness and semantic relevance in AI-generated mathematics. The evaluation underscores the need for rigorous human oversight and contextual understanding when assessing AI contributions to mathematical research.