Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

VisGym: بيئة متنوعة وقابلة للتخصيص وقابلة للتوسع لوكالات متعددة الوسائط

VisGym: بيئة متنوعة وقابلة للتخصيص وقابلة للتوسع لوكالات متعددة الوسائط

الملخص

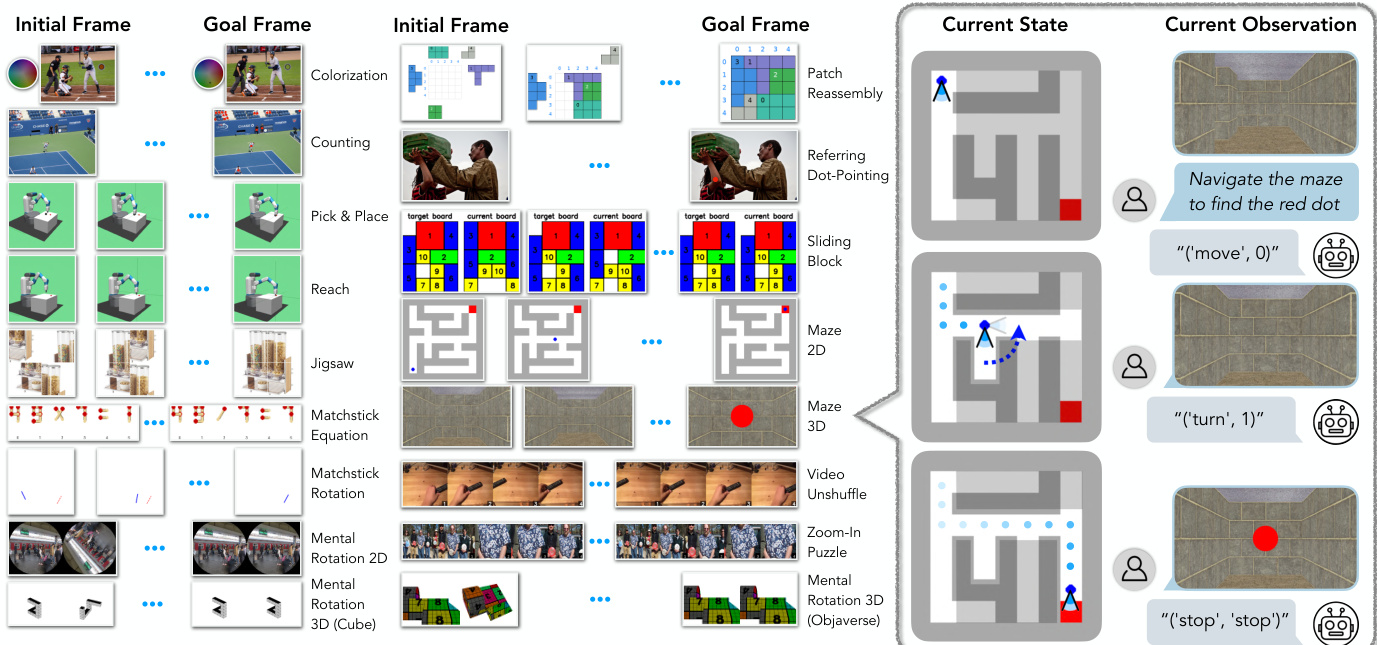

تظل النماذج البصرية-اللغوية الحديثة (VLMs) غير مُوصَفَة بشكل كافٍ في التفاعلات البصرية متعددة الخطوات، خاصةً فيما يتعلق بكيفية دمج الإدراك والذاكرة والفعل على مدى طويل. نقدّم "VisGym"، وهو مختبر مكوّن من 17 بيئة لتقييم وتدريب النماذج البصرية-اللغوية. يغطي هذا المجموعة مسائل رمزية، وفهم الصور الحقيقية، والتنقل، والManipulation (التحكم)، ويوفر تحكمًا مرنًا في مستوى الصعوبة، وتمثيل المدخلات، وطويلة المدى التخطيطي، ونوعية التغذية الراجعة. كما نقدّم حلولًا متعددة الخطوات تُولِّد توضيحات منظمة، مما يمكّن من التدريب المُوجَّه (supervised finetuning). تُظهر تقييماتنا أن جميع النماذج المتقدمة تواجه صعوبات في البيئات التفاعلية، حيث تحقق معدلات نجاح منخفضة في كل من التكوينات السهلة (46.6%) والصعبة (26.0%). تكشف تجاربنا عن قيود ملحوظة: إذ تُعاني النماذج من صعوبة في الاستفادة الفعالة من السياق الطويل، حيث تؤدي السجلات غير المحدودة إلى أداء أسوأ مقارنةً بالنوافذ المقطوعة. علاوةً على ذلك، نجد أن العديد من المهام الرمزية القائمة على النص تصبح أكثر صعوبة بشكل كبير بمجرد تحويلها إلى شكل بصري. ومع ذلك، فإن الملاحظات الهدف الصريحة، والتغذية الراجعة النصية، والتمثيلات الاستكشافية في البيئات التي لا تُعرف دينامياتها أو تكون جزئيًا مرئية، تُسهم في تحسين ملحوظ خلال التدريب المُوجَّه، مما يُبرز أنماط الفشل المحددة ومسارات تحسين اتخاذ القرار البصري متعدد الخطوات. يمكن العثور على الكود والبيانات والنماذج عبر: https://visgym.github.io/.

One-sentence Summary

Researchers from UC Berkeley introduce VisGym, a suite of 17 customizable visual environments to evaluate and train vision-language models (VLMs) on multi-step interactive tasks, revealing that even frontier models struggle with long-horizon reasoning, context management, and visual grounding—yet performance improves with explicit goal cues, textual feedback, and information-revealing demonstrations, offering clear pathways to enhance real-world multimodal agent capabilities.

Key Contributions

- VisGym introduces 17 diverse, customizable environments spanning navigation, manipulation, and symbolic tasks to systematically evaluate VLMs in long-horizon visual decision-making, with fine-grained controls over context length, feedback, and observability to isolate failure modes.

- The framework includes oracle solvers for generating structured demonstrations and reveals key limitations: models perform worse with unbounded context, struggle with visual grounding compared to symbolic inputs, and rely heavily on explicit textual feedback and goal cues to improve success rates.

- Evaluations across 12 state-of-the-art models show consistently low performance (46.6% easy, 26.0% hard), with gains only emerging when using exploratory demonstrations and explicit feedback in partially observable settings, highlighting actionable pathways for improving multimodal agent training.

Introduction

The authors leverage VisGym, a new benchmark suite of 17 customizable, long-horizon environments, to systematically evaluate how vision-language models (VLMs) handle multi-step visual decision-making tasks spanning navigation, manipulation, and symbolic reasoning. Prior work lacks unified, controlled diagnostics across domains, often relying on domain-specific or observational studies that fail to isolate factors like context length, feedback design, or goal visibility. VisGym addresses this by providing fine-grained controls over difficulty, observation modality, and feedback, along with oracle solvers for generating structured training data. Their experiments reveal that even top VLMs struggle with long context, visual grounding, and state inference—achieving only 46.6% and 26.0% success in easy and hard settings—while also identifying actionable levers like explicit goal cues and exploratory demonstrations that improve performance under partial observability.

Dataset

-

The authors use VisGym, a suite of 17 visually interactive environments built atop Gymnasium, to train vision-language models. Each environment supports customizable task parameters and difficulty levels, with detailed specs in Table 2 and Appendix B.

-

Actions are represented as function calls (e.g., ('move', 2) or ('rotate', [90.0, 0.0, 0.0])) rather than traditional vectors, enabling models to reason compositionally. Each task includes natural-language function instructions provided at initialization to support zero-shot execution.

-

Environment feedback is textual (e.g., “Action executed successfully” or “invalid format”), helping models ground actions even with weak visual perception. Feedback also includes step counters and remaining step limits.

-

A built-in solver generates diverse demonstration trajectories by applying heuristic, multi-step strategies — optionally with stochasticity — to support supervised fine-tuning. Solver designs per task are detailed in Appendix A.

-

The system uses a unified step function (Algorithm 1, Appendix D) to parse, validate, execute, and return feedback for each action, enabling modular task creation and consistent supervision across domains.

-

Demonstrations include sequences of observations, actions, and feedback, such as step-by-step rotations, gripper commands, or coordinate-based moves, all logged with execution status and step metadata.

Method

The system employs a modular architecture designed to solve a diverse set of visual reasoning tasks through a sequence of structured actions. At its core, the framework operates by interpreting an environment's current state and generating a sequence of actions to achieve a specified goal. The process begins with a visual observation, which is processed by a vision-language model (VLM) to produce a raw output. This output is then parsed into a specific action, which is executed within the environment. The environment provides feedback, and the process iterates until a termination condition is met.

The architecture is composed of several key components. The first is the environment interface, which defines the state space and action space for each task. For instance, in the Maze 2D environment, the state is represented as a grid with an agent and a target, and the available actions are movement commands. The action execution module is responsible for parsing the VLM's output into a valid action and applying it to the environment. This module includes a generic step function, as detailed in Algorithm 1, which handles parsing, validation, and execution. The function first checks if the action format is valid. If parsing fails, it returns an "invalid format" feedback. If the action name and payload are valid, it calls the Apply function to execute the action and receive the environment's feedback. Termination and truncation are determined within the Apply function, and the reward is computed only upon termination.

The VLM serves as the primary decision-making engine. It takes the current observation as input and generates a sequence of actions. The VLM's output is a raw string that must be parsed into a structured action. For example, in the Matchstick Equation task, the VLM might output a string like ('move', [0, 0, 2, 0]), which is then parsed into the action name move and the payload [0, 0, 2, 0]. The VLM's output is not always correct, and the system must handle invalid actions gracefully. The solver component, which is a set of predefined algorithms, is used to generate the optimal sequence of actions for a given task. For example, in the Maze 2D task, the solver uses a graph search algorithm to find the optimal path, which is then converted into a sequence of move actions. If a target number of steps is requested, the solver pads the sequence with reversible actions to meet the length requirement.

The task-specific solvers are designed to handle the unique requirements of each environment. For example, in the Colorization task, the solver computes the difference between the current and target hues and saturations and generates a sequence of rotate and saturate actions to move toward the correct color. In the Jigsaw task, the solver can use either a reorder strategy, which computes a single permutation to instantly rearrange the pieces, or a swap strategy, which generates a minimal sequence of swap actions. In the Matchstick Equation task, the solver can use a BFS strategy to find the shortest solution path, a DFS strategy to explore the solution space, or an sos strategy to find the shortest path and then pad it with random detours. The padding mechanism is a key feature of the system, allowing it to generate sequences of a specific length by inserting reversible actions. For example, in the Maze 2D task, the solver pads the optimal path with random, reversible move pairs (e.g., move up followed by move down) to meet the target number of steps.

The feedback loop is essential for the system's operation. After each action, the environment provides feedback, which is used to update the current state. The VLM then uses this updated state to generate the next action. This process continues until the goal is achieved or a termination condition is met. The system is designed to be robust to invalid actions, as the step function can handle "invalid action" feedback and continue the process. The visual and text representations of the environments are used to provide the VLM with the necessary information to make decisions. For example, in the Maze 2D task, the visual representation shows the agent's position and the maze structure, while the text representation provides a grid-based representation of the maze. The task-specific instructions provide the VLM with the rules and goals for each task, ensuring that the actions generated are valid and relevant.

Experiment

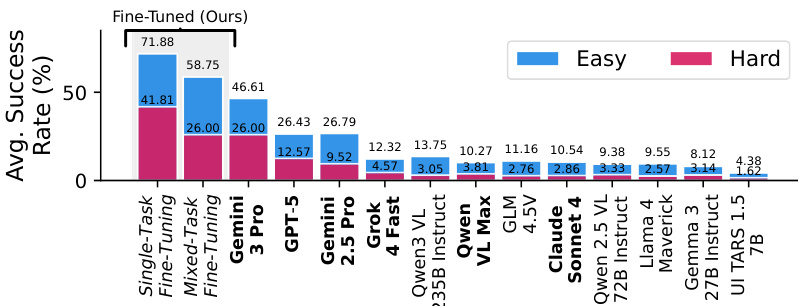

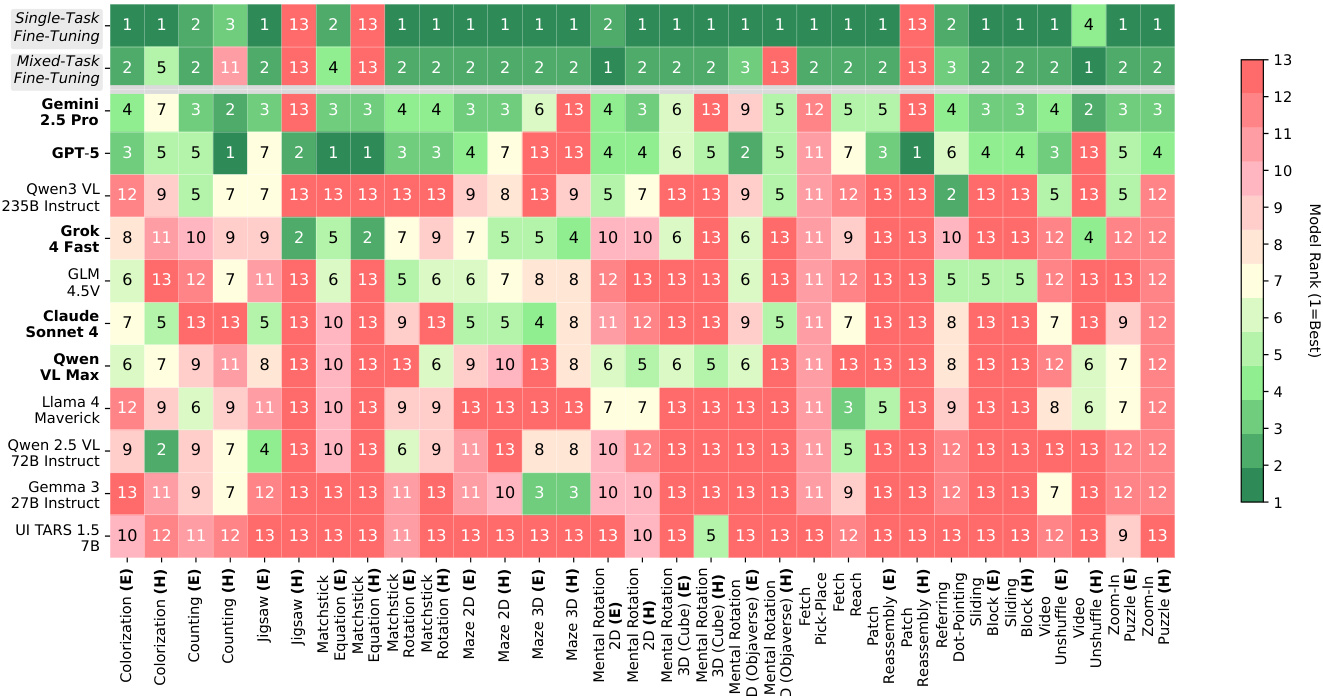

- Evaluated 12 VLMs (proprietary, open-weight, GUI-specialized) on VisGym across 70 episodes per task; best model (Gemini-3-Pro) achieved 46.61% on Easy and 26.00% on Hard settings, revealing significant challenges for frontier models.

- Model specialization observed: GPT-5 excelled in long-context tasks (e.g., Matchstick Rotation), Gemini 2.5 Pro in fine visual perception (e.g., Jigsaw, Maze 2D), Qwen-3-VL in object localization (Referring Dot-Pointing).

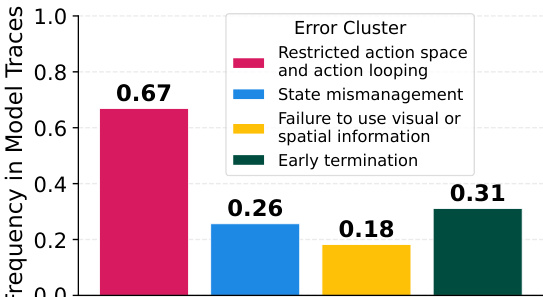

- Common failure modes: action looping (60%+ traces), state mismanagement, early termination, and ignoring visual/spatial cues; weaker models (e.g., UI-Tars 1.5-7B) showed 87% action looping.

- Context truncation improved performance: limiting history to ~4 turns boosted success vs. full history; task-specific gains (e.g., Gemini 2.5 Pro in Maze2D, GPT-5 in Matchstick Rotation).

- ASCII representation boosted GPT-5’s performance 3–4x in most tasks, suggesting visual grounding is its main bottleneck; Gemini 2.5 Pro showed mixed results, open-weight models struggled in both modalities.

- Removing text feedback consistently reduced performance, indicating VLMs rely heavily on textual cues over visual transitions for action validation.

- Providing goal images upfront improved performance across tasks, but GPT-5 and Gemini 2.5 Pro underperformed on Zoom-In Puzzle and Matchstick Equation due to visual misjudgment (80% and 57% error rates in identicality checks).

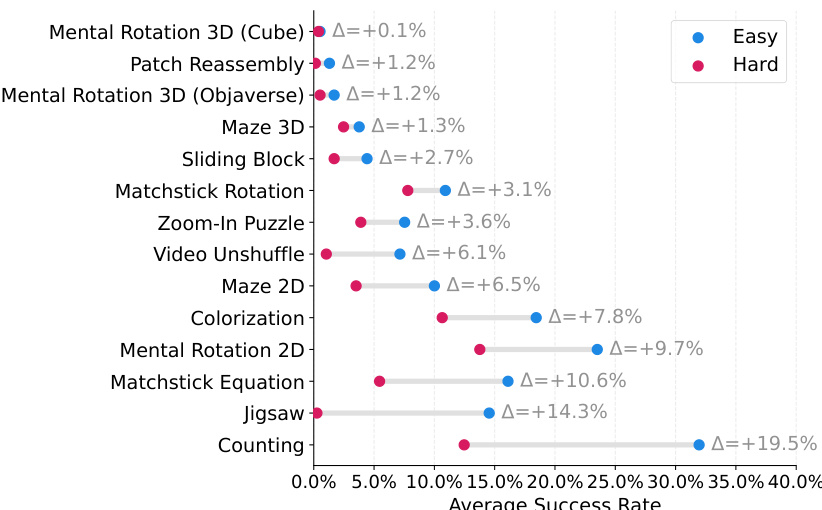

- Supervised fine-tuning on solver-generated trajectories (Qwen2.5-VL-7B) achieved state-of-the-art results; Qwen3-VL-8B showed near-doubled hard-task generalization vs. Qwen2.5-VL.

- Fine-tuning both vision encoder and LLM improved performance most; LLM fine-tuning contributed more, especially in tasks with partial observability or unknown dynamics.

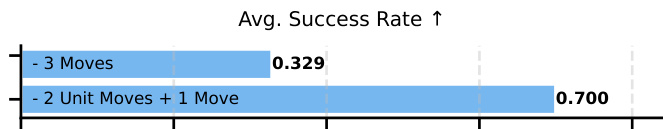

- Information-revealing demonstrations (e.g., structured exploration in Matchstick Rotation) raised success from 32.9% to 70.0%; gains stemmed from state-disambiguating behavior, not trajectory length.

The authors use a controlled experiment to evaluate the impact of demonstration design on model performance in a multi-step visual task. Results show that demonstrations structured to reveal the relationship between action magnitude and perceptual effect—specifically, two unit-scale steps followed by a final aligning move—lead to a significantly higher success rate (0.700) compared to three stochastic moves (0.329). This indicates that information-revealing behaviors in training data substantially improve model performance.

The authors use VisGym to evaluate vision-language models, showing that even the best-performing frontier model, Gemini-3-Pro, achieves only 46.61% success on the easy setting and 26.00% on the hard setting. Results show that models struggle significantly with long-context visual interactions, often failing due to action looping, state mismanagement, early termination, and ignoring visual cues, with performance dropping sharply as task difficulty increases.

The authors use a failure analysis pipeline to identify common failure patterns in model trajectories, and the results show that restricted action space and action looping is the most frequent error, occurring in 67% of traces, followed by state mismanagement, failure to use visual or spatial information, and early termination.

The authors use a table to present the performance of various vision-language models on a set of tasks within the VisGym benchmark, with results categorized by task difficulty (Easy and Hard) and model fine-tuning approach (Single-Task and Mixed-Task). The table shows that fine-tuned models, particularly those using mixed-task fine-tuning, achieve significantly higher success rates across most tasks compared to their untrained counterparts, with the best-performing models often ranking first in the Easy setting. Results show that the performance gap between Easy and Hard settings is substantial for many tasks, and that models fine-tuned on a single task generally outperform those trained on a mixed set of tasks, indicating that task-specific adaptation is beneficial.

The authors use supervised fine-tuning on VisGym to improve model performance, with finetuned models achieving state-of-the-art results on most tasks. The bar chart shows that single-task fine-tuning yields the highest average success rate, reaching 71.88% on the easy setting and 41.81% on the hard setting, significantly outperforming all other models.