Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

スパース自己符号化器の健全性チェック:SAEはランダムベースラインを上回るか?

スパース自己符号化器の健全性チェック:SAEはランダムベースラインを上回るか?

Anton Korznikov Andrey Galichin Alexey Dontsov Oleg Rogov Ivan Oseledets Elena Tutubalina

概要

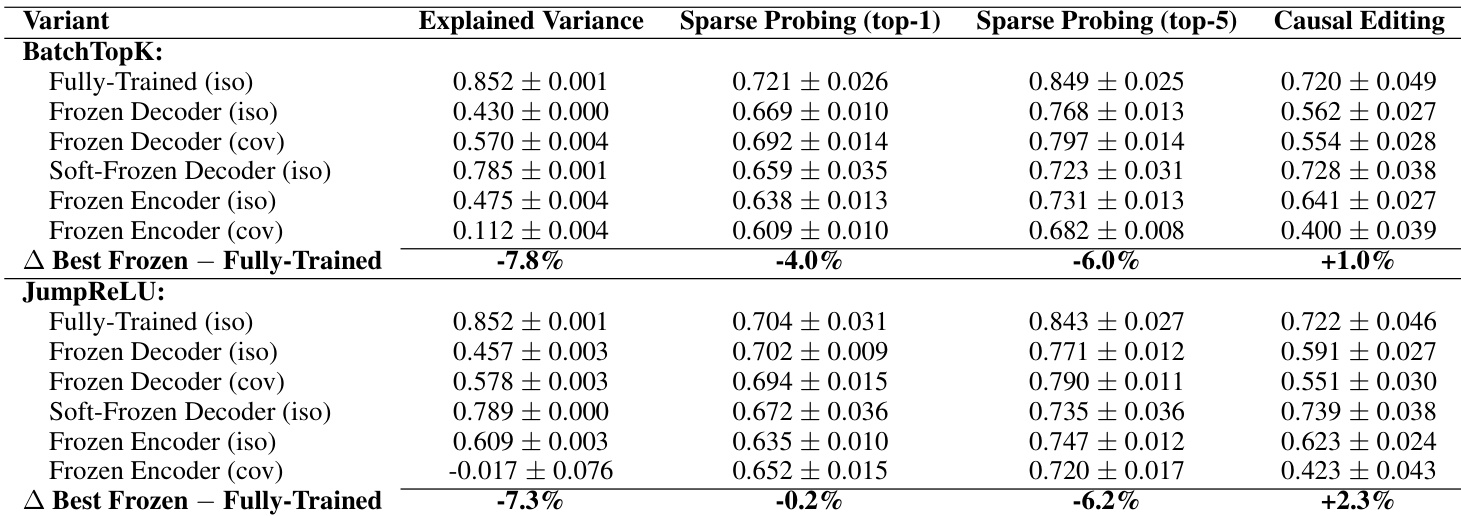

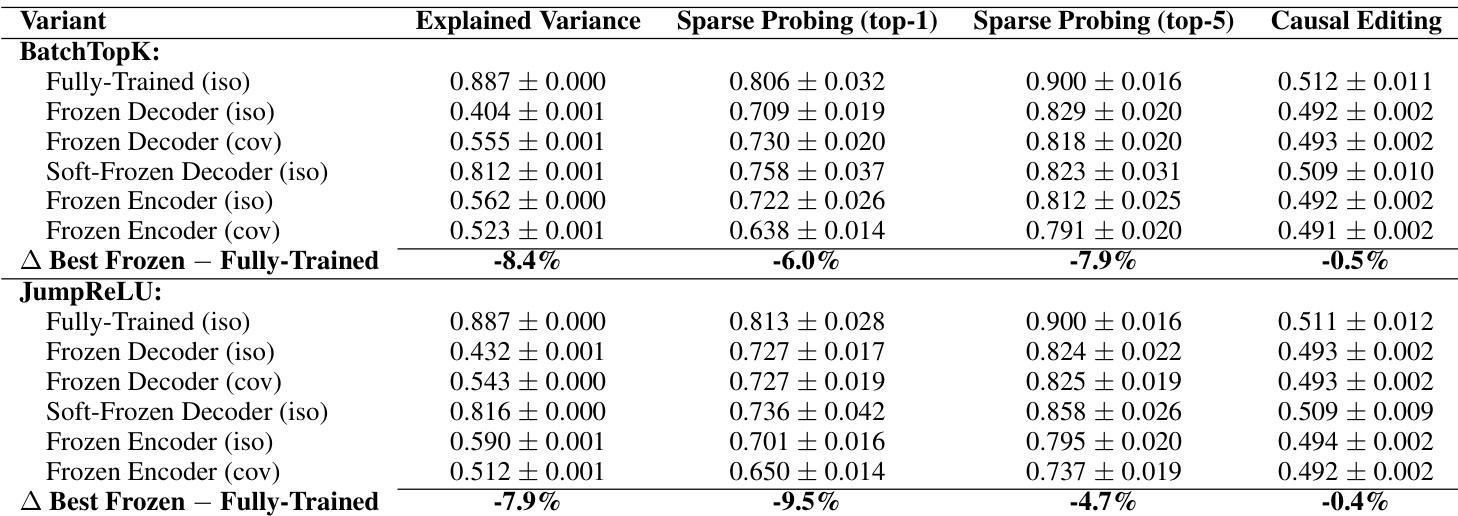

スパース自己符号化器(Sparse Autoencoders: SAEs)は、ニューラルネットワークの活性化を人間が解釈可能な特徴のスパース集合に分解するという点で、ニューラルネットワークの解釈に有望なツールとして注目されている。近年の研究では、複数のSAEの変種が提案され、最先端モデルへのスケーリングも成功している。しかし、その一方で、下流タスクにおける増加する否定的な結果が、SAEsが意味のある特徴を正しく回復しているかどうかに疑問を呈している。この問題を直接検証するために、二つの補完的な評価を実施した。まず、真の特徴が既知である合成設定において、SAEsは71%の分散説明率を達成しているものの、真の特徴のわずか9%しか回復できず、再構成性能が高くても、その核心的なタスクである特徴の回復に失敗していることが示された。次に、実際のモデル活性化に対するSAEの評価として、特徴方向や活性パターンをランダム値に制約する三つのベースラインを導入した。複数のSAEアーキテクチャにわたり広範な実験を行った結果、これらのベースラインは完全に訓練されたSAEsと同等の解釈可能性(0.87 vs 0.90)、スパースプロービング性能(0.69 vs 0.72)、因果的編集性能(0.73 vs 0.72)を達成した。これらの結果から、現状のSAEsはモデルの内部機構を信頼できる形で分解しているとは言えないことが示唆される。

One-sentence Summary

The authors from Skoltech and HSE demonstrate that Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) recover only 9% of true features despite high reconstruction, and show random-baseline variants match trained SAEs in interpretability tasks, challenging SAEs’ reliability for decomposing neural network mechanisms.

Key Contributions

- SAEs fail to recover true features in synthetic settings despite high reconstruction performance, revealing that explained variance does not imply meaningful decomposition—only 9% of ground-truth features were recovered even with 71% variance explained.

- We introduce three simple baselines that fix encoder or decoder parameters to random values, enabling direct evaluation of whether learned feature directions or activations contribute meaningfully to SAE performance on real model activations.

- Across multiple SAE architectures and downstream tasks—including interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing—these baselines match fully trained SAEs, suggesting current SAEs do not reliably learn interpretable internal mechanisms.

Introduction

The authors leverage sparse autoencoders (SAEs) to interpret large language models, aiming to decompose dense activations into human-interpretable features — a goal critical for understanding model behavior, safety, and alignment. However, prior work lacks ground truth to verify whether SAEs recover meaningful structure, and recent studies show SAEs often underperform on downstream tasks despite strong reconstruction scores. The authors introduce three simple baselines — Frozen Decoder, Frozen Encoder, and Soft-Frozen Decoder — that fix or constrain learned parameters to random values, finding these match fully trained SAEs across interpretability, probing, and causal editing tasks. Their synthetic experiments further reveal SAEs recover only high-frequency features, not the intended decomposition, suggesting current evaluation metrics may be misleading and that SAEs may not learn genuinely meaningful features.

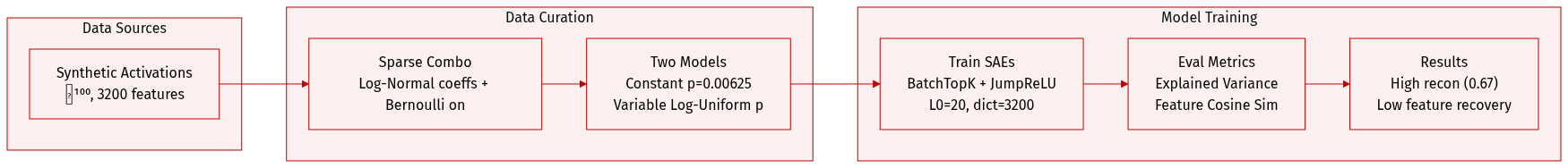

Dataset

- The authors generate synthetic activations in ℝ¹⁰⁰ using an overcomplete dictionary of 3200 ground-truth feature vectors sampled uniformly from the unit sphere.

- Each activation vector is a sparse linear combination of these features, with coefficients drawn from a Log-Normal(0, 0.25) distribution and binary activation indicators from Bernoulli(p_i).

- Two activation probability settings are tested: a Constant Probability Model (p_i = 0.00625) and a Variable Probability Model (p_i ~ Log-Uniform(10⁻⁵.⁵, 10⁻¹.²)), both yielding an average of 20 active features per sample.

- The synthetic dataset is used to train two SAE variants—BatchTopK and JumpReLU—with dictionary size 3200 and target L0 sparsity of 20, matching the ground truth.

- Reconstruction fidelity is measured via explained variance, comparing the SAE’s output to the original activation, normalized by the variance of the mean prediction.

- Feature recovery is evaluated by computing the maximum cosine similarity between each ground-truth feature and its closest SAE decoder vector.

- Despite high explained variance (0.67), neither SAE variant recovers meaningful ground-truth features in the constant probability setting, highlighting alignment challenges.

Method

The authors leverage Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) to decompose neural network activations into interpretable, sparse feature representations. This approach directly addresses polysemanticity — the phenomenon where single neurons encode multiple unrelated concepts — by operating under the superposition hypothesis. This hypothesis posits that neural networks compress more features than their dimensional capacity by encoding them as sparse linear combinations of directions in activation space. For an input activation vector x∈Rn, the model assumes:

x=j=1∑maj⋅fj,where fj are the true underlying feature directions (with m≫n) and aj are sparse, nonnegative coefficients. The SAE approximates this decomposition by learning a dictionary of feature vectors dj and sparse activations zj such that:

x≈x^=j=1∑mzj⋅dj=Wdecz,where Wdec is the decoder matrix whose columns are the learned feature directions. The encoder maps the input via z=f(Wencx+benc), where f is typically a sparsity-inducing activation like ReLU, and benc is a learned bias. The full reconstruction includes a decoder bias: x^=Wdecz+bdec. To enable richer representations, SAEs are typically overcomplete, with an expansion factor k=m/n>1, commonly set to 16, 32, or 64.

Training is guided by a composite objective that balances reconstruction fidelity and sparsity:

L=Ex[∥x−x^∥22+λ∥z∥1],where λ tunes the trade-off. Alternative sparsity mechanisms include L0 constraints or adaptive thresholds, but the core principle remains: optimizing for both reconstruction and sparsity should yield feature directions dj that align with true model features fj and correspond to human-interpretable concepts.

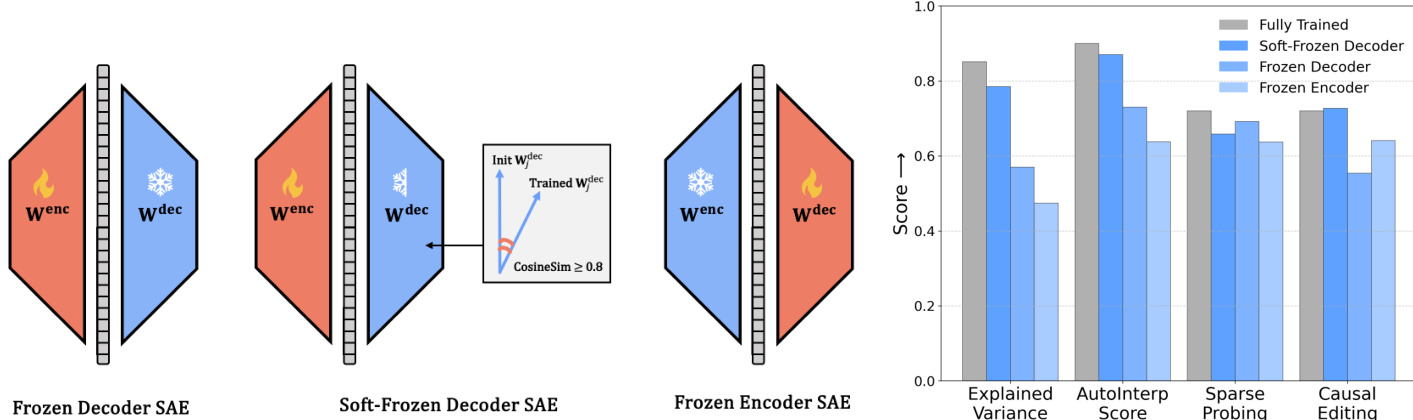

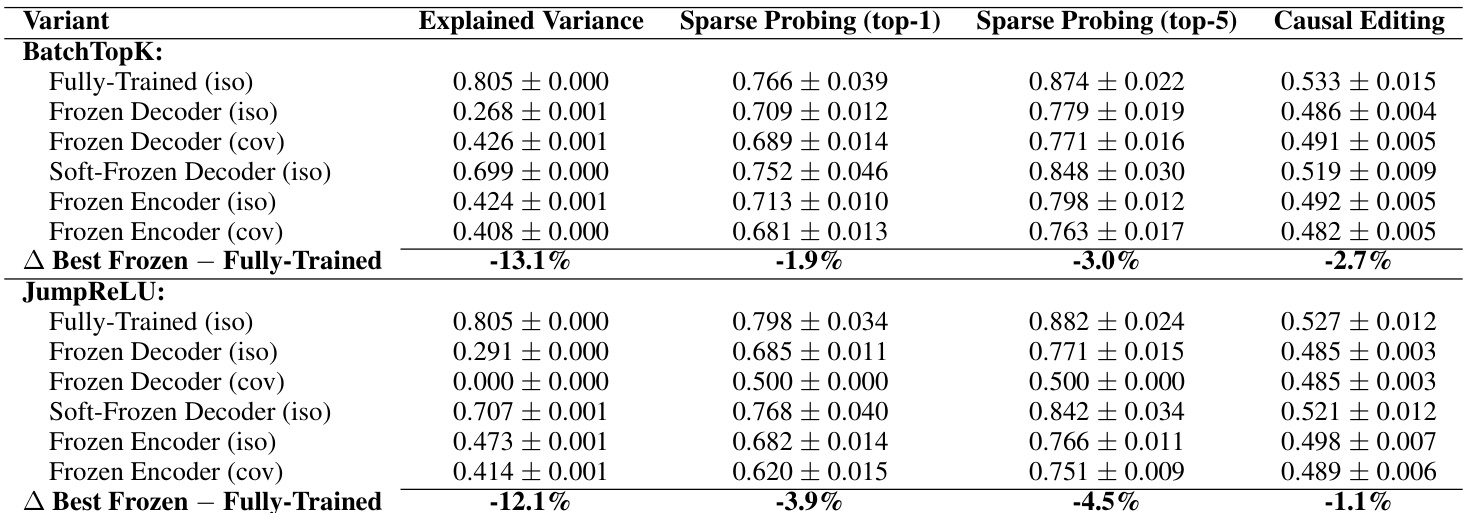

As shown in the figure below, the authors explore three training regimes: Frozen Decoder, Soft-Frozen Decoder, and Frozen Encoder SAEs. In the Frozen Decoder variant, the decoder weights are fixed after initialization, while the encoder is trained. In Soft-Frozen Decoder, the decoder is initialized with pre-trained weights and updated only if the cosine similarity with the initial weights remains above 0.8. In Frozen Encoder, the encoder is fixed and only the decoder is trained. These configurations are evaluated across metrics including Explained Variance, AutoInterp Score, Sparse Probing, and Causal Editing, revealing trade-offs in interpretability and reconstruction performance.

Experiment

- Synthetic experiments show SAEs recover only 9% of true features despite 71% explained variance, indicating reconstruction success does not imply feature discovery.

- On real LLM activations, SAEs with frozen random components match fully trained SAEs in interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing, suggesting performance stems from random alignment rather than learned decomposition.

- Feature recovery is biased toward high-frequency components, leaving the long tail of rare features largely uncovered.

- Soft-Frozen Decoder baselines perform nearly as well as trained SAEs, supporting a “lazy training” regime where minimal adjustments to random initializations suffice for strong metrics.

- TopK SAE succeeds in synthetic settings but fails to translate to real data, where frozen variants still perform comparably, undermining claims of meaningful feature learning.

- Results across vision models (CLIP) echo findings in language models, showing random SAEs produce similarly interpretable features without training.

- Overall, current SAEs do not reliably decompose internal model mechanisms; standard metrics may reflect statistical artifacts rather than genuine feature discovery.

The authors use frozen random baselines to test whether Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) genuinely learn meaningful features or merely exploit statistical patterns. Results show that SAEs with randomly initialized and frozen components perform nearly as well as fully trained ones across reconstruction, interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing metrics, suggesting current SAEs do not reliably decompose model internals into true features.

The authors use frozen random baselines to test whether Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) genuinely learn meaningful features or merely exploit statistical patterns. Results show that SAEs with key components fixed to random values perform nearly as well as fully trained models across reconstruction, interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing tasks, suggesting current SAEs do not reliably decompose internal model mechanisms.

The authors use frozen random baselines to test whether Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) genuinely learn meaningful features or merely exploit statistical patterns. Results show that SAEs with key components fixed at random initialization perform nearly as well as fully trained models across reconstruction, interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing tasks, suggesting current SAEs do not reliably decompose internal model mechanisms.