Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

拡散を用いた生成モデリング

拡散を用いた生成モデリング

Mingyang Deng He Li, Tianhong Li Kaiming He

概要

生成モデルは、そのプッシュフォワード分布がデータ分布と一致するような写像 ( f ) を学習する問題として定式化できる。このプッシュフォワード挙動は、拡散モデルやフローに基づくモデルのように、推論時に反復的に実行可能である。本論文では、学習中にプッシュフォワード分布を進化させ、自然に1ステップ推論を可能にする新しい枠組み「ドリフトモデル(Drifting Models)」を提案する。我々は、サンプルの移動を支配するドリフト場を導入し、分布が一致した際に平衡状態に達するように設計した。これにより、ニューラルネットワークの最適化器が分布を進化させることを可能にする学習目的関数が得られる。実験において、本手法は256×256解像度におけるImageNet上で最先端の性能を達成し、潜在空間ではFIDが1.54、ピクセル空間では1.61を記録した。本研究が高品質な1ステップ生成のための新たな可能性を切り開くことを期待している。

One-sentence Summary

Mingyang Deng, He Li, Tianhong Li, Yilun Du, and Kaiming He from Meta and MIT propose Drifting Models, a new generative paradigm that evolves pushforward distributions during training via a drifting field, enabling one-step inference and achieving SOTA FID scores on ImageNet 256×256.

Key Contributions

- Drifting Models introduce a new generative paradigm that evolves the pushforward distribution during training via a drifting field, enabling one-step inference without iterative sampling or reliance on SDE/ODE dynamics.

- The method trains a single-pass neural network using a novel objective that minimizes sample drift by contrasting data and generated distributions, achieving equilibrium when distributions match.

- On ImageNet 256×256, it sets state-of-the-art one-step FID scores of 1.54 in latent space and 1.61 in pixel space, outperforming prior single-step and many multi-step generative models.

Introduction

The authors leverage a novel training-time distribution evolution framework called Drifting Models, which eliminates the need for iterative inference by learning a single-pass generator that converges to the data distribution through optimization. Unlike diffusion or flow models that rely on SDE/ODE solvers at inference, Drifting Models define a drifting field that pushes generated samples toward real data during training, with drift ceasing at equilibrium when distributions match. Prior one-step methods either distill multi-step models or approximate dynamics, while Drifting Models introduce a direct, non-adversarial, non-ODE-based objective that minimizes sample drift using contrastive-like positive and negative samples—achieving state-of-the-art 1-NFE FID scores of 1.54 in latent space and 1.61 in pixel space on ImageNet 256×256.

Dataset

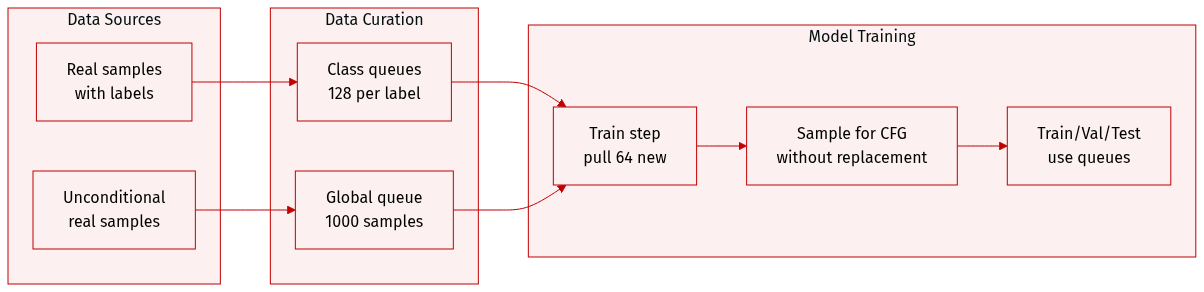

- The authors use a sample queue system to store and retrieve real (positive/unconditional) training data, mimicking the behavior of a specialized data loader while drawing inspiration from MoCo’s queue design.

- For each class label, a queue of size 128 holds labeled real samples; a separate global queue of size 1000 stores unconditional samples used in classifier-free guidance (CFG).

- At every training step, the latest 64 real samples (with labels) are pushed into their respective queues, and the oldest samples are removed to maintain fixed queue sizes.

- During sampling, positive samples are drawn without replacement from the class-specific queue, and unconditional samples come from the global queue.

- This approach ensures statistically consistent sampling while avoiding the complexity of a custom data loader, though the authors note the latter would be more principled.

Method

The authors leverage a novel generative modeling framework called Drifting Models, which conceptualizes training as an iterative evolution of the pushforward distribution via a drifting field. At its core, the model operates by defining a neural network fθ:RC↦RD that maps noise samples ϵ∼pϵ to generated outputs x=fθ(ϵ)∼q, where q=f#pϵ denotes the pushforward distribution. The training objective is to align q with the data distribution pdata by minimizing a drifting field Vp,q(x) that governs how each sample x should move at each training iteration.

The drifting field is designed to induce a fixed-point equilibrium: when q=p, the field vanishes everywhere, i.e., Vp,q(x)=0. This property motivates a training loss derived from a fixed-point iteration: at iteration i, the model updates its prediction to match a frozen target computed by drifting the current sample, leading to the loss function:

L=Eϵ[∥fθ(ϵ)−stopgrad(fθ(ϵ)+Vp,qθ(fθ(ϵ)))∥2].This formulation avoids backpropagating through the distribution-dependent field V by freezing its value at each step, effectively minimizing the squared norm of the drift vector V indirectly.

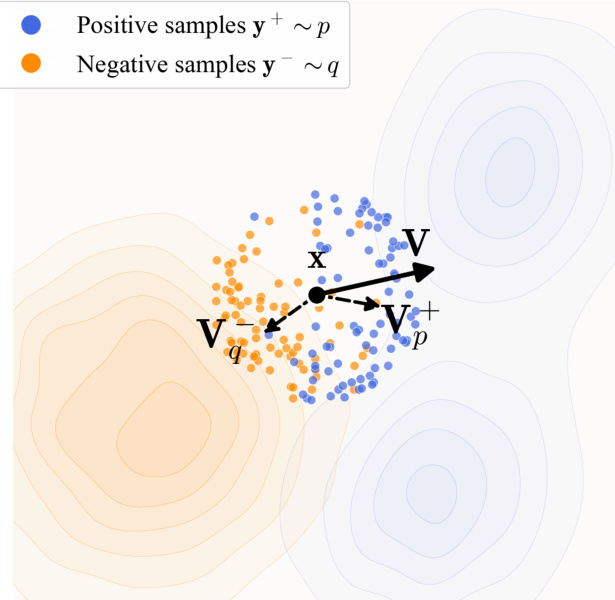

The drifting field Vp,q(x) is instantiated using a kernel-based attraction-repulsion mechanism. It is decomposed into two components: Vp+(x), which attracts x toward data samples y+∼p, and Vq−(x), which repels x away from generated samples y−∼q. The net drift is computed as Vp,q(x)=Vp+(x)−Vq−(x). This design is illustrated in the figure below, which visualizes how a generated sample x (black dot) is pulled toward the data distribution (blue points) and pushed away from the current generated distribution (orange points).

In practice, the field is computed using a normalized kernel k(x,y)=exp(−τ1∥x−y∥), implemented via softmax over pairwise distances within a batch. The kernel is normalized jointly over positive and negative samples, ensuring the field satisfies the anti-symmetry property Vp,q=−Vq,p, which guarantees equilibrium when p=q. The implementation further includes a second normalization over the generated samples within the batch to improve stability.

To enhance performance, the authors extend the drifting loss to feature spaces using pre-trained self-supervised encoders (e.g., ResNet, MAE). The loss is computed across multiple scales and spatial locations of the feature maps, with each feature independently normalized to ensure robustness across different encoders and feature dimensions. The overall loss aggregates contributions from all features, weighted by normalized drift vectors.

For conditional generation, the framework naturally supports classifier-free guidance by mixing unconditional data samples into the negative set, effectively training the model to approximate a linear combination of conditional and unconditional distributions. This guidance is applied only at training time, preserving the one-step (1-NFE) generation property at inference.

The generator architecture follows a DiT-style Transformer with patch-based tokenization, adaLN-zero conditioning, and optional random style embeddings. Training is performed in latent space using an SD-VAE tokenizer, with feature extraction applied in pixel space via the VAE decoder when necessary. The model is trained using stochastic mini-batch optimization, where each batch contains generated samples (as negatives) and real data samples (as positives), with the drifting field computed empirically over these sets.

Experiment

- Toy experiments demonstrate the method’s ability to avoid mode collapse, even from collapsed initializations, by allowing samples to be attracted to underrepresented modes of the target distribution.

- Anti-symmetry in the drifting field is critical; breaking it causes catastrophic failure, confirming its role in achieving equilibrium between p and q.

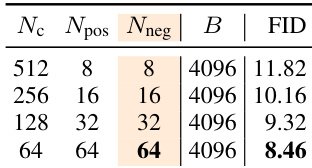

- Increasing positive and negative sample counts improves generation quality under fixed compute budgets, aligning with contrastive learning principles.

- Feature encoder quality significantly impacts performance; latent-MAE outperforms standard SSL encoders, with wider and longer-trained variants yielding further gains.

- In ImageNet 256×256, the method achieves state-of-the-art 1-NFE FID scores (1.54 in latent space, 1.61 in pixel space), outperforming multi-step and GAN-based one-step methods while using far fewer FLOPs.

- Pixel-space generation is more challenging than latent-space but benefits from stronger encoders like ConvNeXt-V2 and extended training.

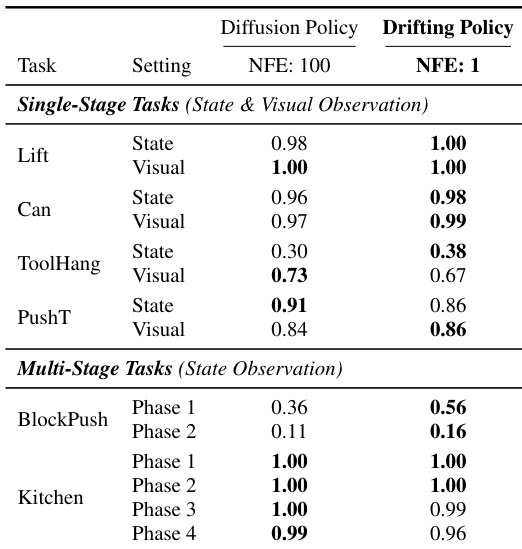

- On robotic control tasks, the one-step drifting model matches or exceeds 100-NFE diffusion policies, showing cross-domain applicability.

- Kernel normalization enhances performance but is not strictly necessary, as even unnormalized variants avoid collapse and maintain reasonable results.

- CFG scale trades off FID and IS similarly to diffusion models; optimal FID occurs at α=1.0, equivalent to “no CFG” in standard frameworks.

- Generated images are visually distinct from their nearest neighbors in training data, indicating novelty rather than memorization.

The authors evaluate their one-step Drifting Policy on robotic control tasks, replacing the multi-step generator of Diffusion Policy. Results show that their method matches or exceeds the performance of the 100-step Diffusion Policy across both single-stage and multi-stage tasks, demonstrating its effectiveness as a generative model in robotics.

The authors demonstrate that increasing the number of negative samples under a fixed computational budget leads to improved generation quality, as measured by lower FID scores. This aligns with the observation that larger sample sets enhance the accuracy of the estimated drifting field, which drives the generator toward better alignment with the target distribution. The trend holds across different configurations, reinforcing the importance of sample diversity in training stability and performance.

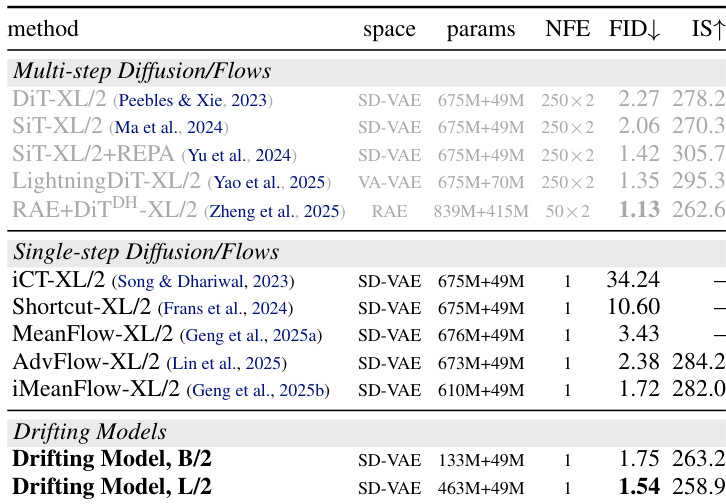

The authors evaluate their Drifting Model against multi-step and single-step diffusion/flow methods on ImageNet 256×256, showing that their one-step approach achieves competitive or superior FID scores while requiring only a single network function evaluation. Results indicate that larger model sizes improve performance, with the L/2 variant reaching a state-of-the-art 1.54 FID without classifier-free guidance. The method outperforms prior single-step generators and matches or exceeds multi-step models in quality despite its computational efficiency.

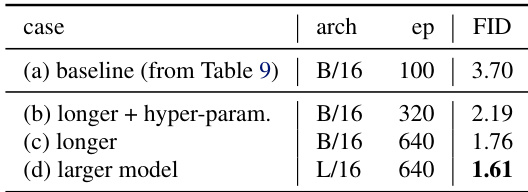

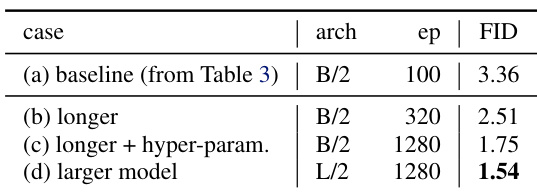

The authors demonstrate that extending training duration and tuning hyperparameters significantly improves generation quality, as shown by the drop in FID from 3.36 to 1.75. Scaling up the model size further reduces FID to 1.54, indicating that architectural capacity and training scale are key drivers of performance in their framework.

The authors demonstrate that extending training duration and scaling up model size significantly improves generation quality, as shown by the progressive FID reduction from 3.70 to 1.61 under controlled conditions. These improvements are achieved without altering the core method, indicating that performance gains stem from increased capacity and longer optimization rather than architectural changes.