Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

MemoryLLM:即插即用の解釈可能な順方向メモリを備えたトランスフォーマー

MemoryLLM:即插即用の解釈可能な順方向メモリを備えたトランスフォーマー

Ajay Jaiswal Lauren Hannah Han-Byul Kim Duc Hoang Arnav Kundu Mehrdad Farajtabar Minsik Cho

概要

大規模言語モデル(LLM)におけるトランスフォーマー構成要素の動作メカニズムを理解することは、近年の人工知能分野における技術革新の根幹に位置する重要な課題である。本研究では、フィードフォワードモジュール(FFN)の解釈可能性に関する課題を再検討し、FFNと自己注意機構(self-attention)を分離することを目的とした「MemoryLLM」を提案する。このアプローチにより、FFNを文脈に依存しないトークン単位のニューラル検索メモリとして独立して解析可能とする。具体的には、入力トークンがFFNパラメータ内のメモリ領域にどのようにアクセスするか、および異なる下流タスクにおけるFFNメモリの重要性について検証する。MemoryLLMは、自己注意機構とは独立してトークン埋め込みを直接用いてFFNを学習することで、文脈に依存しないFFNを実現する。この手法により、FFNはトークン単位の参照テーブル(ToL: Token-wise Lookups)として事前に計算可能となり、VRAMとストレージ間でのオンデマンドなデータ転送が可能になるほか、推論効率の向上も実現する。さらに、従来のトランスフォーマー設計とMemoryLLMの間に位置する「Flex-MemoryLLM」を導入する。このアーキテクチャは、文脈に依存しないトークン単位の埋め込みでFFNを学習することに起因する性能ギャップを緩和する。

One-sentence Summary

Apple researchers propose MemoryLLM, a transformer architecture that decouples feed-forward networks (FFNs) from self-attention to treat them as context-free, token-indexed neural memory, enabling interpretable analysis and pre-computed lookups that reduce VRAM usage while maintaining performance through Flex-MemoryLLM variants.

Key Contributions

- MemoryLLM decouples feed-forward networks (FFNs) from self-attention by training them in isolation on context-free token embeddings, enabling interpretable token-wise neural retrieval memory without relying on residual stream interactions.

- The architecture supports pre-computed token lookups (ToLs) for FFNs, allowing plug-n-play memory offloading to storage and improving inference efficiency, validated across 250M, 750M, and 1B parameter scales.

- Flex-MemoryLLM bridges performance gaps by splitting FFN parameters into context-aware and context-free components, maintaining competitiveness with conventional transformers while preserving interpretability and efficiency benefits.

Introduction

The authors leverage the observation that feed-forward networks (FFNs) in transformers—though parameter-heavy—are poorly understood due to their tight coupling with self-attention modules, which obscure their function as interpretable memory systems. Prior work attempted to reverse-engineer FFNs as key-value memories but relied on post-hoc analysis of pretrained models, requiring calibration datasets and offering only indirect, non-discrete query mappings. MemoryLLM addresses this by decoupling FFNs entirely from self-attention during training, treating them as context-free, token-indexed neural retrieval memories that can be precomputed and stored. This enables both interpretable token-level memory access and efficient inference via plug-n-play memory offloading. To mitigate performance loss from full decoupling, they also introduce Flex-MemoryLLM, which blends context-free and context-aware FFNs to bridge the gap with conventional transformers.

Method

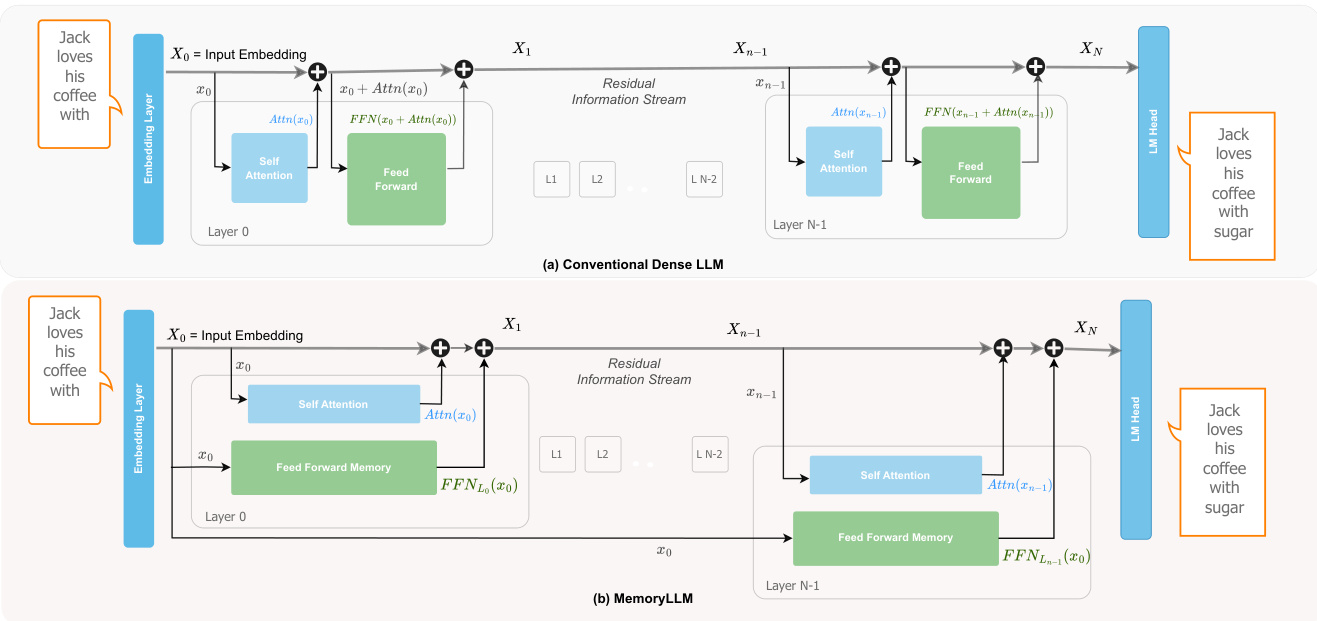

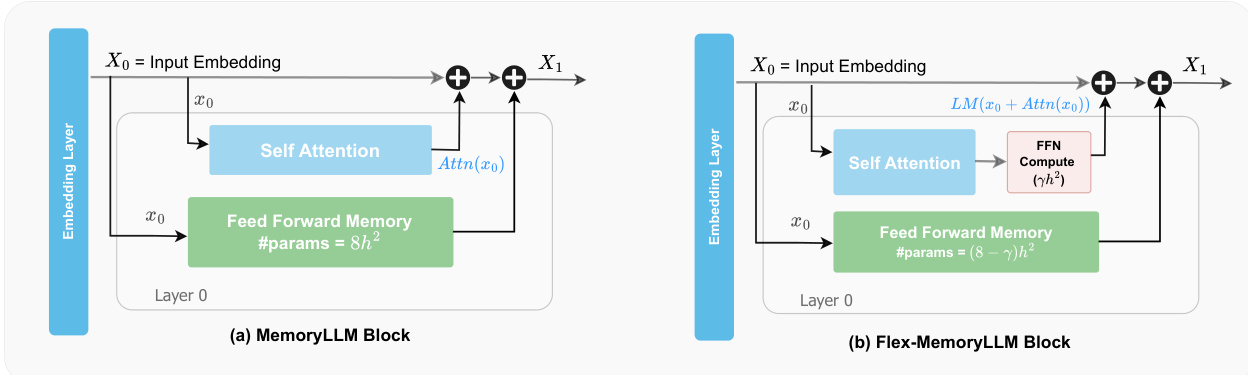

The authors leverage a novel transformer architecture called MemoryLLM to decouple feed-forward networks (FFNs) from the residual stream and self-attention modules, enabling a deterministic and interpretable analysis of FFN functionality. In conventional LLMs, FFNs operate on a dynamically evolving residual stream that combines contextual information from prior layers, making their internal mechanisms opaque. MemoryLLM addresses this by training all FFN modules across transformer layers directly on the initial token embeddings X0, which are static and derived solely from token IDs via the tokenizer. This design isolates FFNs from contextual dependencies, allowing them to function as context-free token-indexed memory reservoirs.

Refer to the framework diagram, which contrasts the conventional dense LLM with MemoryLLM. In the conventional architecture, each transformer layer L computes self-attention on the residual stream XL, adds the result to XL, and then applies the FFN to this sum. In MemoryLLM, the self-attention module operates as usual, but the FFN at layer L receives the original input embedding X0 instead of the residual stream. The output of layer L is then computed as:

XL+1=XL+Attn(XL)+FFN(X0)This parallelization of context-aware self-attention and context-free FFN computation preserves the residual flow while enabling FFNs to be interpreted as neural key-value memories over a finite, human-interpretable query space—the vocabulary.

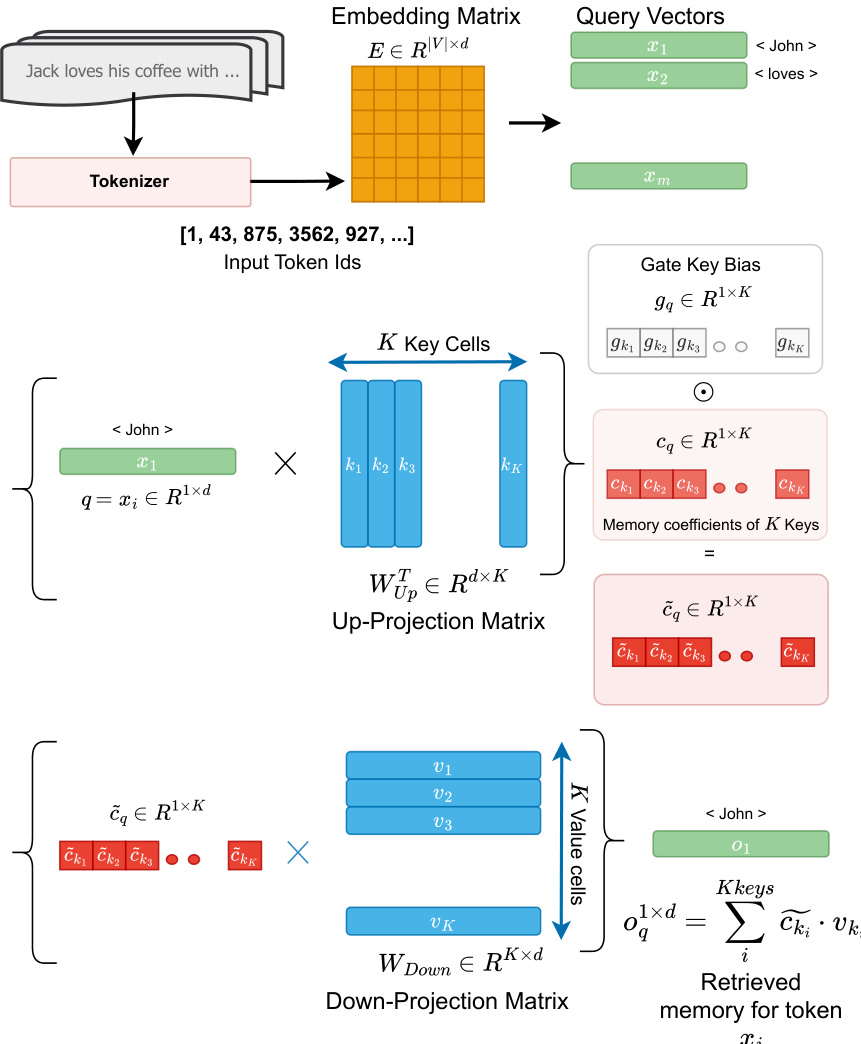

To formalize this interpretation, the authors introduce the TKV (token-key-value) framework. Within each FFN, the up-projection matrix WUp is treated as a set of K key vectors, and the down-projection matrix WDown as corresponding value vectors. The gate-projection matrix WGate acts as a learned reweighting function that modulates the contribution of each key. For a query vector q=xi corresponding to token ti, the memory retrieval process involves two steps. First, the memory cell coefficients cki are computed via dot product between q and the columns of WUp⊤, then reweighted element-wise by the gate vector gki:

c~ki=(q1×d⋅WUp[:,ki]⊤)×gkiSecond, the retrieved output is a weighted sum of the value vectors vki:

FFN(X0q)=σq1×d=i∑Kc~ki⋅vkiThis framework eliminates the need for laborious reverse-engineering of input prefixes and provides a direct mapping from token IDs to memory cells.

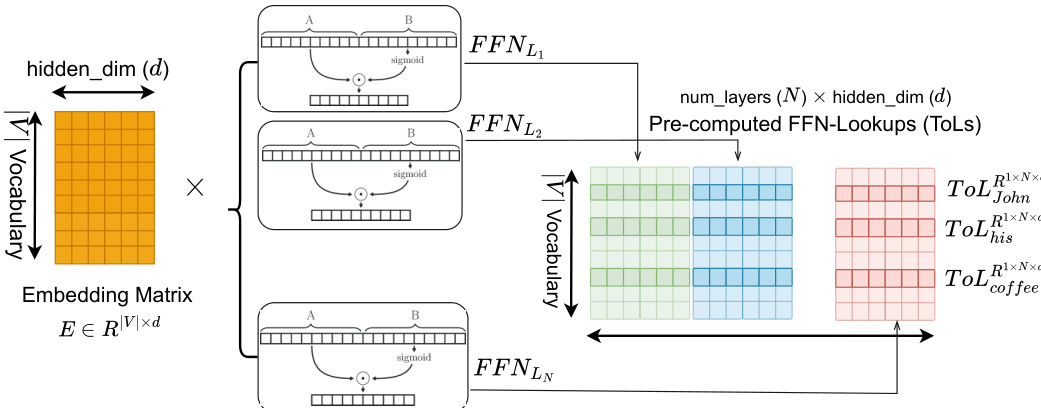

The static nature of FFN inputs in MemoryLLM enables a significant efficiency gain: FFN outputs for all vocabulary tokens can be pre-computed offline and stored as token-wise lookup tables (ToLs). Each ToL for token ti is a concatenation of FFN outputs across all N layers:

ToLxti1×(N×d)=Concatk=0N−1{FFNLk(xti),dim=1}These ToLs can be offloaded to storage and asynchronously prefetched during inference, reducing both computational load and VRAM usage. The authors further propose an on-demand plug-n-play policy that caches ToLs for frequent tokens (following Zipf’s law) and loads less frequent ones as needed.

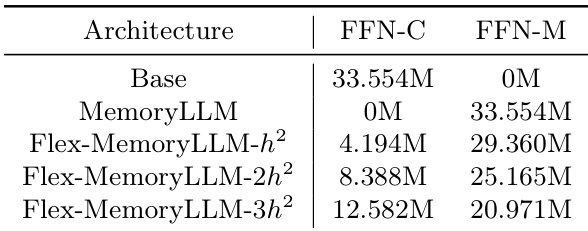

To bridge the performance gap between MemoryLLM and conventional dense LLMs, the authors introduce Flex-MemoryLLM. This hybrid architecture splits the FFN parameters in each layer into two components: FFN Compute (FFN-C), a dense module operating on the residual stream to enhance computational capacity, and FFN Memory (FFN-M), a context-free memory module trained on X0 like in MemoryLLM. The total parameter count remains identical to the base model, but a portion of the FFN parameters (e.g., 5h2 for β=3) can be offloaded as static ToLs during inference. The output of layer L in Flex-MemoryLLM is:

XL+1=XL+Attn(XL)+FFN-C(XL)+FFN-M(X0)This design allows for a smooth trade-off between performance and efficiency, enabling models with significantly fewer active parameters to match or even exceed the performance of dense counterparts.

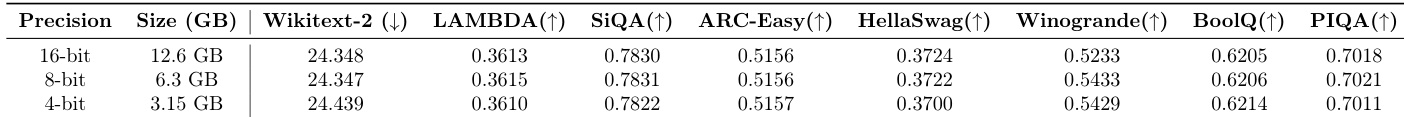

The authors also explore storage optimization for ToLs, estimating the total storage size as:

Storage Size=vocab size×num layers×hidden dim×bits per paramFor a 1B parameter MemoryLLM with 24 layers and 2048 hidden dimension, this amounts to approximately 12.6 GB in F16 precision. They suggest quantization, low-rank compression, and layer-wise compression as strategies to reduce this footprint.

Experiment

- Semantically similar tokens activate similar keys in FFN memory, forming interpretable clusters (e.g., punctuation, names, locations), enabling targeted memory editing or toxicity control.

- Clustering strength remains high across all layers, with terminal layers showing more outlier keys, suggesting focused token-level information convergence.

- Reducing FFN contribution via interpolation harms recall-heavy tasks more than reasoning tasks, confirming FFNs act as token-indexed retrieval memory.

- MemoryLLM underperforms base LLMs when comparing total parameters but outperforms them when comparing active parameters, validating its efficiency via precomputed ToLs.

- MemoryLLM and Flex-MemoryLLM outperform pruned base models at matching active parameter counts, offering a viable alternative to pruning techniques.

- ToLs exhibit strong low-rank properties, especially in terminal layers, enabling ~2x storage reduction via SVD with minimal performance loss.

- Dropping ToLs from middle layers causes minimal performance degradation, indicating high redundancy and offering a practical compression strategy.

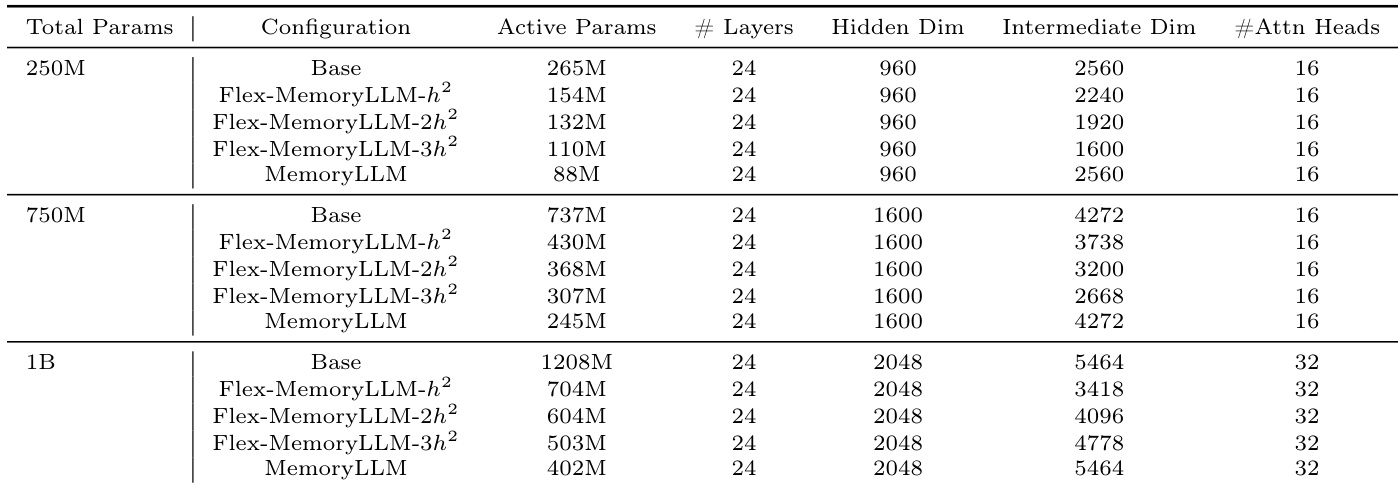

The authors use a consistent 24-layer architecture across models with varying total parameter counts, adjusting intermediate dimensions to control active parameter counts while keeping hidden dimensions and attention heads fixed. MemoryLLM and Flex-MemoryLLM variants achieve lower active parameter counts than their base counterparts by design, enabling more efficient deployment without altering layer count or core structure. These configurations support comparisons of performance versus active parameter efficiency, particularly when evaluating memory-based architectures against conventional pruning methods.

The authors evaluate MemoryLLM-1B under varying precision levels for token-wise lookup tables, observing that reducing precision from 16-bit to 4-bit incurs only marginal performance changes across multiple downstream tasks. Results show that even at 4-bit precision, the model maintains competitive scores, suggesting strong resilience to low-precision quantization. This supports the feasibility of deploying MemoryLLM with significantly reduced storage requirements without substantial degradation in task performance.

The authors use a controlled interpolation parameter to reduce FFN contribution and observe that tasks relying on recall or retrieval suffer greater performance degradation compared to reasoning tasks. Results show that as FFN influence decreases, models retain stronger logical inference capabilities while losing accuracy on fact-based tasks. This suggests FFNs in MemoryLLM serve as token-indexed memory stores more critical for knowledge retrieval than for reasoning.

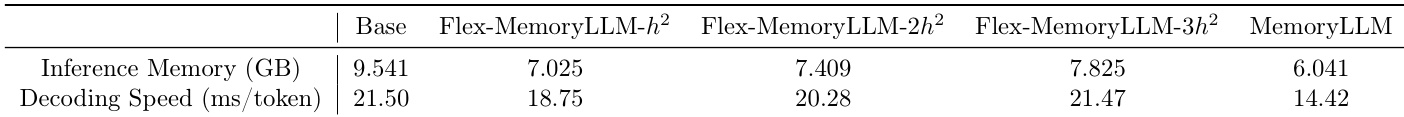

The authors evaluate MemoryLLM and its variants against a base model, finding that MemoryLLM achieves the lowest inference memory usage while also delivering the fastest decoding speed per token. Flex-MemoryLLM variants show trade-offs between memory and speed, with higher hidden dimension scaling increasing memory but not consistently improving speed. Results indicate MemoryLLM’s architecture enables more efficient inference without compromising throughput.

The authors use a parameter allocation strategy to split feed-forward network components into context-dependent and context-free memory modules, showing that shifting more parameters to the memory module reduces the context-dependent component while maintaining total parameter count. Results show that architectures like Flex-MemoryLLM can flexibly balance these components, enabling trade-offs between computational efficiency and memory capacity without altering overall model size.