Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

視覚生成がマルチモーダル・ワールド・モデルを通じて人間のような推論を解き放つ

視覚生成がマルチモーダル・ワールド・モデルを通じて人間のような推論を解き放つ

Jialong Wu Xiaoying Zhang Hongyi Yuan Xiangcheng Zhang Tianhao Huang Changjing He Chaoyi Deng Renrui Zhang Youbin Wu Mingsheng Long

概要

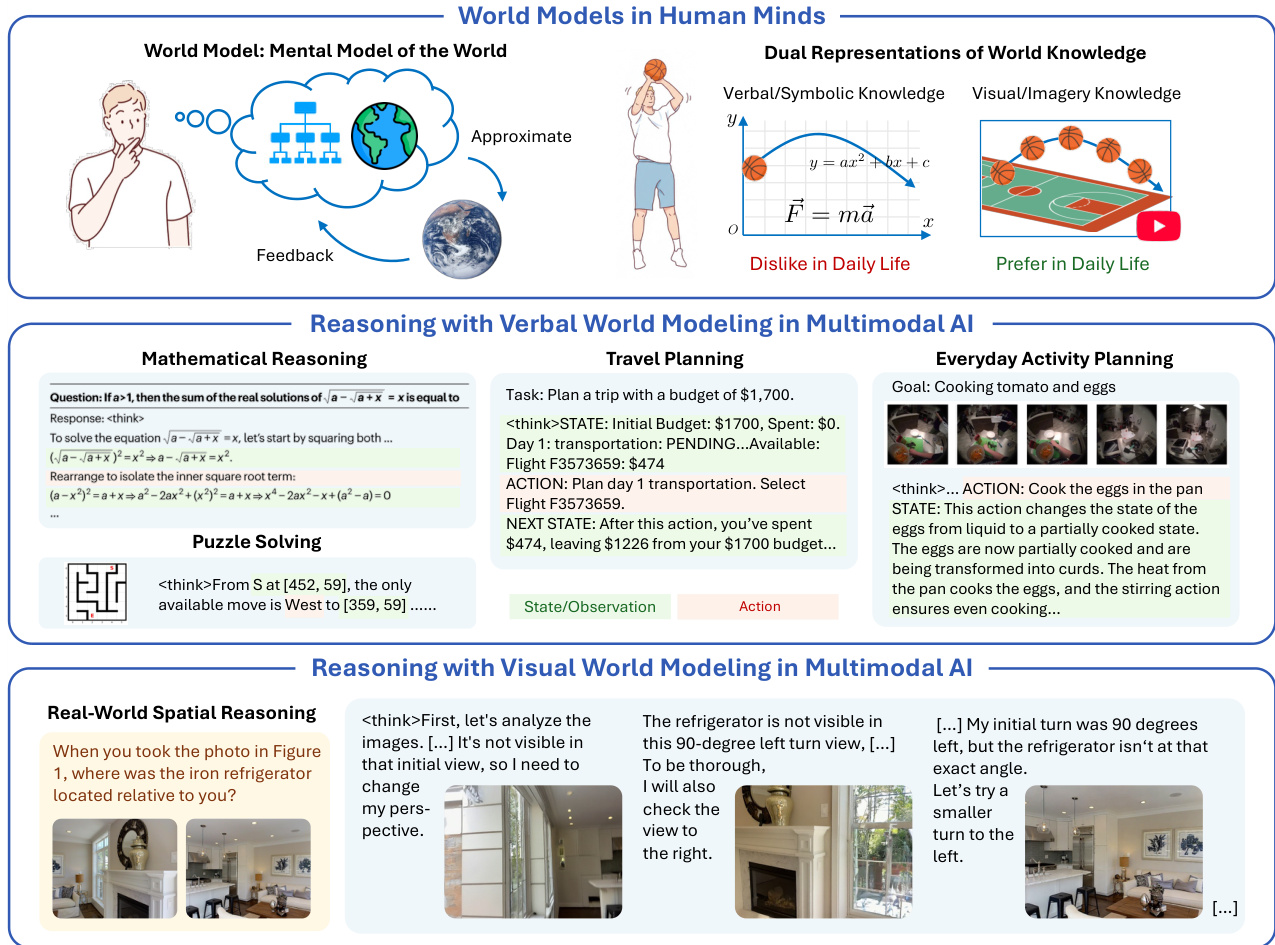

人間は内部の世界モデルを構築し、そのモデル内の概念を操作することで推論を行う。近年のAI分野における進展、特にチェーン・オブ・シンキング(CoT)推論の発展により、こうした人間の認知能力が近似的に再現されつつある。世界モデルは、大規模言語モデル(LLM)の内部に埋め込まれていると考えられている。現在のシステムでは、数学やプログラミングなど形式的・抽象的な領域において、主に言語的推論に依拠することで専門家レベルの性能が達成されている。しかし、物理的・空間的知能といった領域では、より豊かな表現能力と事前知識を必要とするため、依然として人間には大きく及ばない。このような状況のもと、言語的生成と視覚的生成を両立できる統合型多モーダルモデル(UMM)の登場により、補完的な多モーダル経路に基づいたより人間らしい推論への関心が高まっている。しかしながら、こうしたモデルの実際の利点はまだ明確でない。本論文は、世界モデルの視点から、視覚的生成が推論にどのように、またどのような状況で有益であるかを初めて体系的に検証するものである。我々の核心的な主張は「視覚的優位性仮説(Visual Superiority Hypothesis)」である。すなわち、特に物理世界に根ざしたタスクにおいて、視覚的生成はより自然に世界モデルとして機能する一方で、純粋に言語的な世界モデルは表現能力の限界や十分な事前知識の欠如によって性能のボトルネックに直面するという主張である。理論的には、内部世界モデルをCoT推論の核心的構成要素として形式化し、異なる種類の世界モデルの違いを分析する。実証的には、視覚的・言語的CoT推論を交互に組み合わせる必要があるタスクを同定し、新たな評価セット「VisWorld-Eval」を構築した。最先端のUMMを用いた制御実験の結果、視覚的モデルが有利なタスクにおいて、交互に視覚的・言語的CoTを用いる手法は、純粋な言語的CoTに比べて著しく優れた性能を示したが、その他のタスクでは明確な優位性は認められなかった。本研究を通じて、より強力で人間らしい多モーダルAIの実現に向け、多モーダル世界モデルの潜在的価値が明確に示された。

One-sentence Summary

Tsinghua University and ByteDance Seed researchers propose the visual superiority hypothesis, showing that interleaved visual-verbal chain-of-thought reasoning in unified multimodal models outperforms verbal-only approaches on physical-world tasks, validated via their new VisWorld-Eval benchmark.

Key Contributions

- The paper introduces the visual superiority hypothesis, arguing that for physical-world tasks, visual generation serves as a more natural world model than verbal reasoning alone, which faces representational and knowledge bottlenecks.

- It formalizes world modeling in CoT reasoning and introduces VisWorld-Eval, a new benchmark suite designed to evaluate interleaved visual-verbal reasoning on tasks requiring explicit visual simulation.

- Empirical results on state-of-the-art UMMs show interleaved CoT significantly outperforms verbal-only CoT on visual-favoring tasks, while offering no advantage on tasks not requiring visual modeling, clarifying the scope of multimodal reasoning benefits.

Introduction

The authors leverage unified multimodal models (UMMs) to explore how visual generation enhances reasoning by acting as explicit visual world models—complementing the verbal world models embedded in large language models. While current AI systems excel in abstract domains using verbal chain-of-thought reasoning, they struggle with physical and spatial tasks due to representational bottlenecks and insufficient visual prior knowledge. The authors introduce the “visual superiority hypothesis,” arguing that for tasks grounded in the physical world, visual generation provides richer, more grounded representations. Their main contribution is a principled theoretical framework linking world modeling to reasoning, plus the VisWorld-Eval benchmark—a controlled suite of tasks designed to isolate when visual generation helps. Empirical results show interleaved verbal-visual CoT significantly improves performance on tasks requiring spatial or physical simulation, but offers no gain on simpler symbolic tasks like Sokoban, validating their hypothesis.

Dataset

The authors use VisWorld-Eval, a curated suite of seven reasoning tasks designed to evaluate visual world modeling, organized into two categories: world simulation and world reconstruction.

-

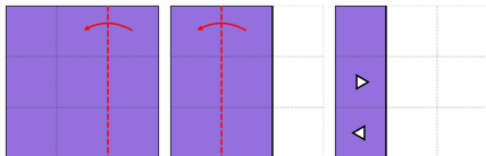

Paper Folding (adapted from SpatialViz-Bench): Simulates unfolding paper after folds and hole punches. Grid sizes 3–8, 1–4 folds; holes in 5 shapes. Test set uses max difficulty (8x8 grid, 4 folds). CoTs generated via rule-based templates, refined by Gemini 2.5 Pro. Visual world modeling interleaves images of unfolding steps; verbal modeling uses grid matrices; implicit modeling skips state tracking.

-

Multi-hop Manipulation (based on CLEVR): Objects (cubes, spheres, cylinders) in Blender-rendered scenes undergo spatial operations (add/remove/change). Queries target final layout. Test prompts vary initial objects (3–6) and operations (1–5). CoTs simulate step-by-step execution, refined by Gemini 2.5 Pro.

-

Ball Tracking (adapted from RBench-V): Predicts ball trajectory after elastic wall reflections. Ball starts with green arrow direction; 4–8 randomized holes. Test cases require ≥1 wall bounce. CoTs generated by Seed 1.6, explaining frame-to-frame dynamics.

-

Sokoban: Grid puzzles (6–10x10) with one box and target. CoTs use search algorithm to find optimal path; only key steps rendered (approach, push, direction change). Augmented with randomized detours for reflection. CoTs from Seed 1.6. Visual modeling interleaves rendered steps; verbal removes images; implicit masks coordinates with [masked].

-

Maze: Fixed 5x5 grid puzzles. CoTs from rule-based templates, rewritten for naturalness. Visual modeling interleaves rendered path steps; verbal and implicit follow Sokoban protocol, masking positions as [masked].

-

Cube 3-view Projection (from SpatialViz-Bench): Infers unseen orthographic view from isometric + two orthographic views. Grids 3–5, two cube colors. Test set uses random grid sizes. CoTs construct queried view, mark occlusions with auxiliary color, count cubes—rewritten by Gemini 2.5 Pro. Visual modeling adds image of queried view; verbal uses character matrices for color encoding.

-

Real-world Spatial Reasoning (subset of MMSI-Bench): Uses real-world camera-object/region positional questions. Training CoTs generated via visual-CoT pipeline using SFT-trained BAGEL for novel view synthesis, then filtered and rewritten by Gemini 2.5 Pro.

All tasks use question-answering format with verifiable answers. Training data includes chain-of-thoughts (CoTs) generated via templates or models, refined for clarity. Visual world modeling interleaves intermediate state images; verbal modeling uses symbolic representations; implicit modeling removes or masks explicit state tracking. Training and test sample counts per task are summarized in Table 2.

Method

The authors formalize a world-model perspective on multimodal reasoning, conceptualizing the underlying environment as a multi-observable Markov decision process (MOMDP). This framework posits that a multimodal model operates by maintaining an internal representation of the world state, which is inferred from multiple, potentially incomplete, observations across different modalities. The core of this approach lies in two atomic capabilities: world reconstruction and world simulation. World reconstruction enables the model to infer the complete structure of the world from partial observations, allowing it to generate novel views of the same state. This is formalized as encoding a set of observations into an internal representation, s^=enc(oϕ1,…,oϕn), which can then be decoded to synthesize an unseen observation, o^ϕn+1=dec(s^,ϕn+1). In modern generative models, this capability is realized through end-to-end novel view generation, pθ(oϕn+1∣oϕ1,…,oϕn). The second capability, world simulation, allows the model to predict the future evolution of the world state. This is formalized as predicting the transition of the current state and action, s^′∼pred(s^,a), or more commonly in generative models, predicting future observations, pθ(ot+1∣o≤t,a≤t). The authors argue that deliberate reasoning, such as chain-of-thought, is a process of manipulating these internal world observations. This is formalized as a sequence of reasoning steps and observations, R=(r1,o1),(r2,o2),…,(rH,oH), where each step ri is a logical operation and oi is an observation generated by invoking one of the atomic world modeling capabilities. This formulation is modality-agnostic, allowing for verbal, visual, or implicit world modeling.

The model architecture is built upon a unified multimodal foundation, specifically the BAGEL model, which is designed to handle both verbal and visual generation. The training process is designed to optimize the model for generating interleaved verbal and visual reasoning steps. It begins with supervised fine-tuning (SFT) on task-specific datasets, where both the verbal reasoning steps and visual intermediate outputs are optimized. The loss function for visual world modeling combines cross-entropy for verbal generation with a flow-matching loss for visual generation, which is designed to learn the internal representations required for novel view synthesis. The training objective is to minimize the following loss: Lθ(Q,I,R,A)=−∑i=1H+1∑j=1∣ri∣logpθ(ri,j∣ri,<j,Ri)+∑i=1HEt,ϵ∥vθ(oit,t∣R~i)−(ϵ−oi)∥22. Following SFT, reinforcement learning from verifiable rewards (RLVR) is applied to further refine the model. During RL, the verbal generation component is optimized using GRPO, while the visual generation component is regularized via the KL-divergence with respect to the SFT-trained reference model to prevent degradation. The overall training framework is designed to enable the model to perform complex multimodal reasoning by explicitly generating and manipulating visual and verbal observations.

Experiment

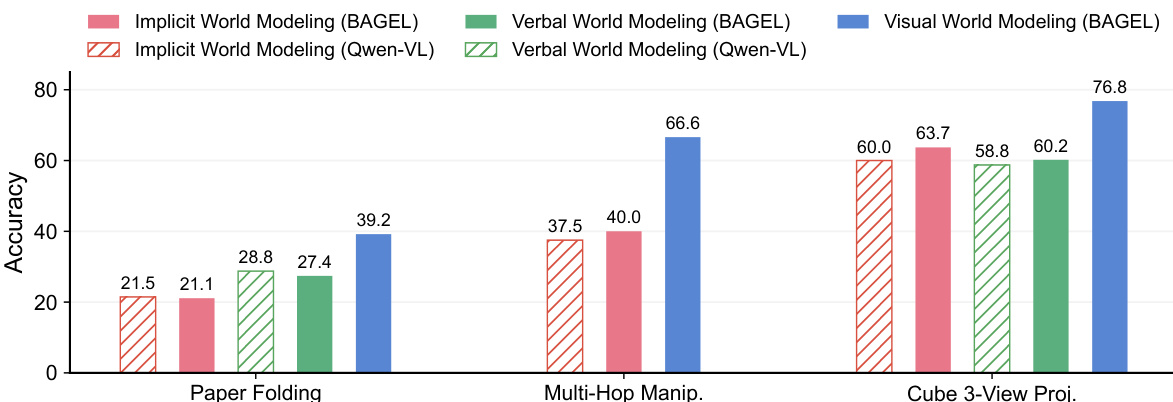

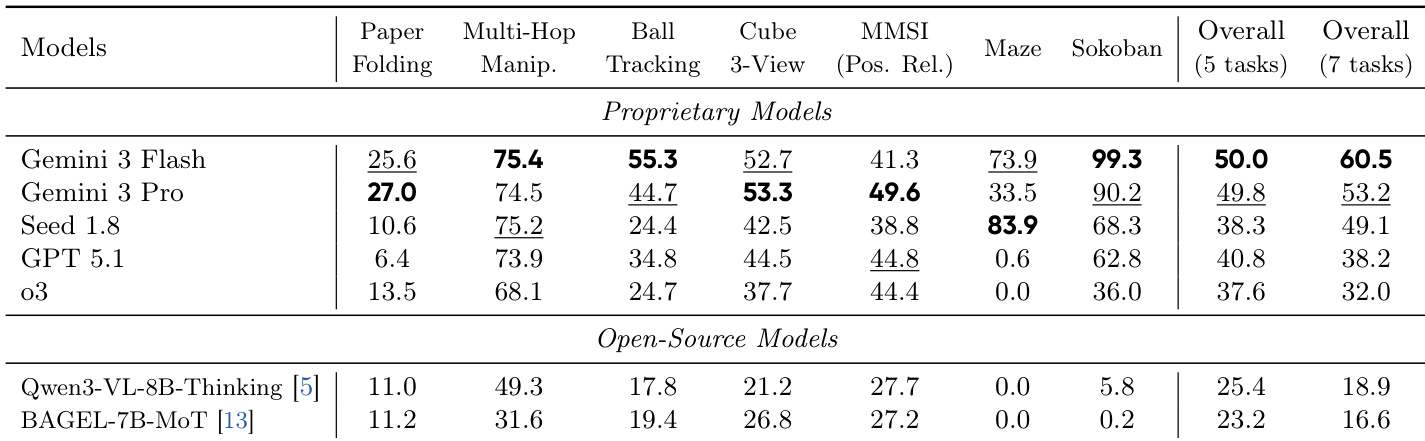

- Evaluated visual world modeling via VisWorld-Eval, a 7-task suite spanning synthetic and real-world domains; advanced VLMs (Gemini 3 Flash/Pro) outperform others but remain suboptimal on complex tasks like paper folding and spatial reasoning.

- Visual world modeling significantly boosts performance on world simulation tasks (paper folding, ball tracking, multi-hop manipulation) via richer spatial grounding; achieves 4x sample efficiency gain over verbal modeling in paper folding.

- Enhances world reconstruction tasks (cube 3-view, real-world spatial reasoning) by leveraging visual priors; maintains ~10% accuracy advantage even on out-of-distribution cube stacks (size 6) and achieves >50% fidelity in view synthesis vs. near-zero for verbal modeling.

- Offers no benefit on grid-world tasks (maze, Sokoban); implicit world modeling suffices, with internal model representations emerging post-pretraining and further refined via SFT without explicit coordinate supervision.

- UMMs outperform VLM baselines (Qwen2.5-VL) even when VLMs are fine-tuned on identical verbal CoT data, confirming visual modeling’s inherent advantage, not compromised verbal reasoning.

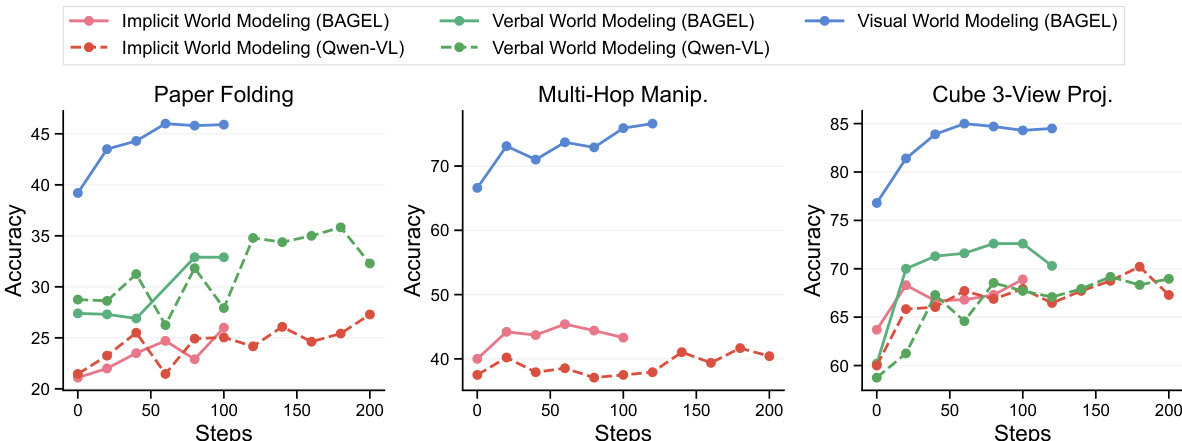

- RLVR improves all CoT formulations but does not close the performance gap; visual world modeling gains persist, suggesting its superiority is structural, not training-limited.

- Qualitative analysis reveals hallucinations in verbal reasoning (especially symmetry tasks) and generation artifacts in visual modeling, with spatial understanding still limited across viewpoints—expected to improve with stronger base models and curated data.

The authors use a bar chart to compare the performance of different models and reasoning methods on three tasks: Paper Folding, Multi-Hop Manipulation, and Cube 3-View Projection. Results show that visual world modeling consistently outperforms verbal and implicit world modeling across all tasks, with the largest gains observed in Multi-Hop Manipulation and Cube 3-View Projection. In Paper Folding, visual world modeling achieves the highest accuracy, while implicit and verbal world modeling show similar, lower performance.

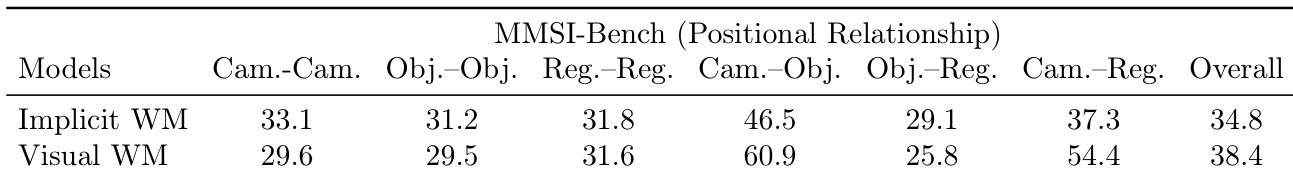

The authors compare implicit and visual world modeling on MMSI-Bench positional relationship tasks, showing that visual world modeling achieves higher accuracy on Cam.-Obj. and Cam.-Reg. subtasks, while implicit world modeling performs better on Obj.-Obj. and Obj.-Reg. The overall performance of visual world modeling is higher, indicating its effectiveness in spatial reasoning.

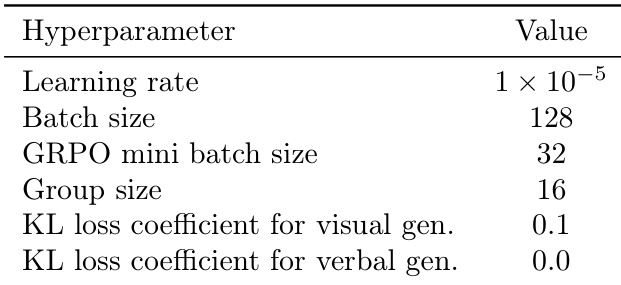

The authors use supervised fine-tuning with specific hyperparameters, including a learning rate of 1×10−5, a batch size of 128, and a GRPO mini batch size of 32, to train their models. The KL loss coefficient for visual generation is set to 0.1, while the coefficient for verbal generation is 0.0, indicating a focus on visual generation during training.

The authors use the VisWorld-Eval suite to evaluate advanced VLMs, reporting zero-shot performance across seven tasks. Results show that Gemini 3 Flash and Gemini 3 Pro significantly outperform other models, particularly on complex tasks like paper folding and ball tracking, though overall performance remains suboptimal.

The authors use supervised fine-tuning to evaluate the impact of different chain-of-thought formulations on multimodal reasoning tasks. Results show that visual world modeling significantly outperforms verbal and implicit world modeling on paper folding and multi-hop manipulation, where spatial reasoning requires precise geometric understanding. In contrast, for cube 3-view projection, visual world modeling achieves higher accuracy and better world-model fidelity compared to verbal approaches, though performance plateaus and hallucinations remain an issue.