Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

エージェンティック推論による大規模言語モデル

エージェンティック推論による大規模言語モデル

概要

推論は、推論、問題解決、意思決定といった基本的な認知プロセスを支える基盤となる。大規模言語モデル(LLM)は閉じた世界(closed-world)設定において優れた推論能力を示すが、開かれたかつ動的な環境では困難に直面する。エージェント型推論(agentic reasoning)は、LLMを継続的な相互作用を通じて計画・行動・学習を行う自律的エージェントとして再定義するというパラダイムの転換をもたらす。本調査では、エージェント型推論を三つの補完的な次元に沿って体系化する。第一に、環境の動的性を三つの層に分類する。第一層は、安定した環境下における計画、ツール利用、探索といった基本的な単一エージェント能力を構築する「基礎的エージェント型推論」であり、第二層は、フィードバック、記憶、適応を通じてこれらの能力を自己改善する「自己進化型エージェント型推論」であり、第三層は、協調、知識共有、共有目標を伴う協働環境へと知能を拡張する「集団的マルチエージェント推論」である。これらの層にわたり、テスト時におけるインタラクションを構造的調整によってスケーラブルに拡張する「コンテキスト内推論」を、強化学習および教師あり微調整によって行動を最適化する「訓練後推論」とに区別する。さらに、科学、ロボティクス、医療、自律研究、数学といった実世界の応用分野およびベンチマークにおいて代表的なエージェント型推論フレームワークを検討する。本調査は、エージェント型推論の手法を統合的なロードマップとして構築し、思考と行動の橋渡しを実現するとともに、個人化、長期的なインタラクション、世界モデル化、スケーラブルなマルチエージェント学習、実世界への展開に向けたガバナンスといった未解決課題と今後の研究方向性を提示する。

One-sentence Summary

Researchers from UIUC, Meta, Amazon, Google DeepMind, UCSD, and Yale propose a unified framework for agentic reasoning, where LLMs act as autonomous agents that plan, act, and learn through continual interaction, advancing beyond static inference to dynamic, multi-agent, and self-evolving systems for real-world applications.

Key Contributions

- The paper introduces agentic reasoning as a paradigm that reframes LLMs as autonomous agents capable of planning, acting, and learning through interaction, addressing their limitations in open-ended, dynamic environments beyond static benchmarks.

- It organizes agentic reasoning into three layers—foundational (planning, tool use, search), self-evolving (feedback-driven adaptation, memory refinement), and collective (multi-agent coordination)—and distinguishes between in-context orchestration and post-training optimization methods.

- The survey contextualizes these frameworks across real-world applications and benchmarks in science, robotics, healthcare, and math, while identifying open challenges including personalization, long-horizon interaction, and scalable multi-agent governance.

Introduction

The authors leverage agentic reasoning to reframe large language models as autonomous agents that plan, act, and learn through continuous interaction — moving beyond static, one-shot inference toward dynamic, goal-driven behavior. While prior LLMs excel in closed-world tasks like math or code, they falter in open, evolving environments where adaptation, tool use, and long-horizon planning are essential. Existing agent frameworks often treat reasoning as a byproduct of architecture rather than a unifying mechanism. The authors’ main contribution is a unified, three-layer taxonomy — foundational (planning, tool use, search), self-evolving (feedback, memory, adaptation), and collective (multi-agent collaboration) — paired with two optimization modes: in-context orchestration and post-training fine-tuning. This roadmap systematically maps how reasoning scales across environmental dynamics, agent interaction, and system constraints, while grounding the framework in real-world applications and benchmarks. They also outline open challenges including personalization, long-horizon credit assignment, world modeling, scalable multi-agent training, and governance for real-world deployment.

Dataset

The authors use a diverse collection of benchmarks and datasets to evaluate agentic reasoning across tool use, memory, planning, multi-agent coordination, embodiment, scientific discovery, autonomous research, clinical applications, web navigation, and general tool invocation. Here’s a structured overview:

-

Tool Use Benchmarks

- Single-turn: ToolQA (1,530 dialogues, 13 tools), APIBench (16,450 instruction-API pairs from HuggingFace/TorchHub), ToolLLM-ToolBench (16,464 APIs across 49 categories), MetaTool (20K+ entries, 200 tools), T-Eval (23,305 test cases, 15 tools), GTA (229 tasks, 14 tools), ToolRet (7.6K retrieval tasks, 43K tools).

- Multi-turn: ToolAlpaca (3,938 instances, 400+ APIs), API-Bank (1,888 dialogues, 73 runnable APIs), UltraTool (5,824 samples, 22 domains), ToolFlow (224 expert tasks, 107 tools), MTU-Bench (54,798 dialogues, 136 tools), m & m’s (4K+ multimodal tasks, 33 tools).

- These are used to train and evaluate models like Gorilla, ToolLLaMA, and others, with emphasis on generalization, planning, and real-world API grounding.

-

Memory and Planning Benchmarks

- Memory Management: PerLTQA (8.5K QA pairs), ELITR-Bench (noisy transcripts), Multi-IF (4.5K tri-turn convos), MultiChallenge (273 dialogues), MemBench (60K episodes), MMRC (multimodal), LOCOMO (19-session dialogues), MemSim (2,900 synthetic trajectories), LONGMEMEVAL (up to 1.5M tokens), REALTALK (21-day human convos), MemoryAgentBench (unified tasks), Mem-Gallery (multimodal), Evo-Memory (test-time learning).

- Planning & Feedback: ALFWorld (interactive envs), PlanBench, ACPBench (formal planning), TEXT2WORLD (world modeling), REALM-Bench (dynamic disruptions), TravelPlanner (itineraries), FlowBench, UrbanPlanBench (procedural planning).

- Metrics focus on retention, recall, coherence, adaptability, and iterative reasoning over long horizons.

-

Multi-Agent Systems

- Game-based: MAgent (grid-worlds), Pommerman, SMAC (StarCraft), MineLand & TeamCraft (Minecraft), Melting Pot (social dilemmas), BenchMARL, Arena (cooperative/adversarial games).

- Simulation-centric: SMARTS & Nocturne (driving), MABIM (inventory), IMP-MARL (infrastructure), POGEMA (pathfinding), INTERSECTIONZOO (eco-driving), REALM-Bench (logistics/disaster).

- Language & Social: LLM-Coordination (Hanabi/Overcooked), AVALONBENCH (Avalon), Welfare Diplomacy, MAgIC (social deduction), BattleAgentBench, COMMA (multimodal puzzles), IntellAgent (retail/airline), MultiAgentBench (Minecraft/coding/bargaining).

- Evaluated on coordination, win rates, social welfare, communication, and emergent behavior.

-

Embodied Agents

- AgentX (vision-language in driving/sports), BALROG (RL planning), ALFWORLD (text-based 3D), AndroidArena (GUI mobile tasks), StarDojo (Stardew Valley), MindAgent & NetPlay (multiplayer games), OSWorld (desktop productivity).

- Test perception, action grounding, and planning in partially observable, dynamic environments.

-

Scientific Discovery Agents

- DISCOVERYWORLD (virtual lab), ScienceWorld (elementary experiments), ScienceAgentBench (paper-derived tasks), AI Scientist (end-to-end pipeline), LAB-Bench (biology), MLAgentBench (ML workflows).

- Assess hypothesis testing, automation, and long-horizon scientific reasoning.

-

Autonomous Research Agents

- WorkArena & WorkArena++ (enterprise tickets), OfficeBench (productivity apps), PlanBench & FlowBench (workflow graphs), ACPBench (triad roles), TRAIL (trace debugging), CLIN (lifelong learning), Agent-as-a-Judge (peer review), InfoDeepSeek (information seeking).

- Emphasize goal decomposition, iteration, and evaluation in knowledge workflows.

-

Medical and Clinical Agents

- AgentClinic (virtual hospital), MedAgentBench (medical QA), MedAgentsBench (multi-hop reasoning), EHRAgent (EHR tables), MedBrowseComp (web browsing), ACC (trustworthiness), MedAgents (multi-agent dialogue), GuardAgent (privacy safeguard).

- Evaluated for correctness, safety, evidence alignment, and clinical reliability.

-

Web Agents

- WebArena (90+ websites, click-based), VisualWebArena (visual rendering), WebVoyager (long-horizon navigation), Mind2Web (cross-domain), WebCanvas (layout manipulation), WebLINX (info gathering), BrowseComp-ZH (Chinese sites), LASER/WebWalker/AutoWebBench (structured navigation).

- Focus on layout parsing, dynamic content handling, and policy generalization.

-

General Tool-Use Agents

- GTA (realistic user queries), NESTFUL (nested APIs), CodeAct (executable functions), RestGPT (RESTful APIs), Search-o1 (sequential retrieval), Agentic RL (RL + tools), ActionReasoningBench (action consequences), R-Judge (safety evaluation).

- Test compositional planning, side-effect reasoning, and toolchain coordination.

The datasets are typically used in training splits with mixture ratios tuned for generalization, often processed via instruction fine-tuning, human verification, or synthetic generation. Cropping strategies (e.g., token limits) and metadata construction (e.g., tool categories, domain tags, reliability flags) are applied to support structured evaluation and cross-benchmark comparison.

Method

The authors present a comprehensive framework for agentic reasoning systems, structured around a core paradigm shift from static language modeling to dynamic, goal-directed behavior. This framework is built upon a formalization of the agent's interaction with its environment as a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP), which explicitly separates internal reasoning from external actions. The agent's policy is decomposed into two distinct components: an internal reasoning policy, πreason(zt∣ht), which generates a reasoning trace zt (e.g., a chain-of-thought), and an external execution policy, πexec(at∣ht,zt), which produces an action at (e.g., a tool call or final answer). This "think-act" structure is fundamental to the agentic paradigm, enabling computation in a latent space before committing to an action.

The overall system architecture, as illustrated in the framework diagram, is designed to support a spectrum of reasoning capabilities, from foundational to self-evolving. The foundational layer, detailed in Section 3, focuses on enabling the agent to perform complex planning, use tools, and conduct web searches. This involves decomposing tasks into subtasks, selecting appropriate tools, and orchestrating actions. The system leverages in-context planning methods, such as workflow design and tree search, to structure the reasoning process. For tool use, the agent interleaves reasoning with actions, allowing it to dynamically query external APIs or databases to gather information and execute tasks, a process that can be guided by structured prompting or demonstrated in a few-shot manner. This is further enhanced by in-context search, where the agent's reasoning is augmented with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to ground its responses in external knowledge sources.

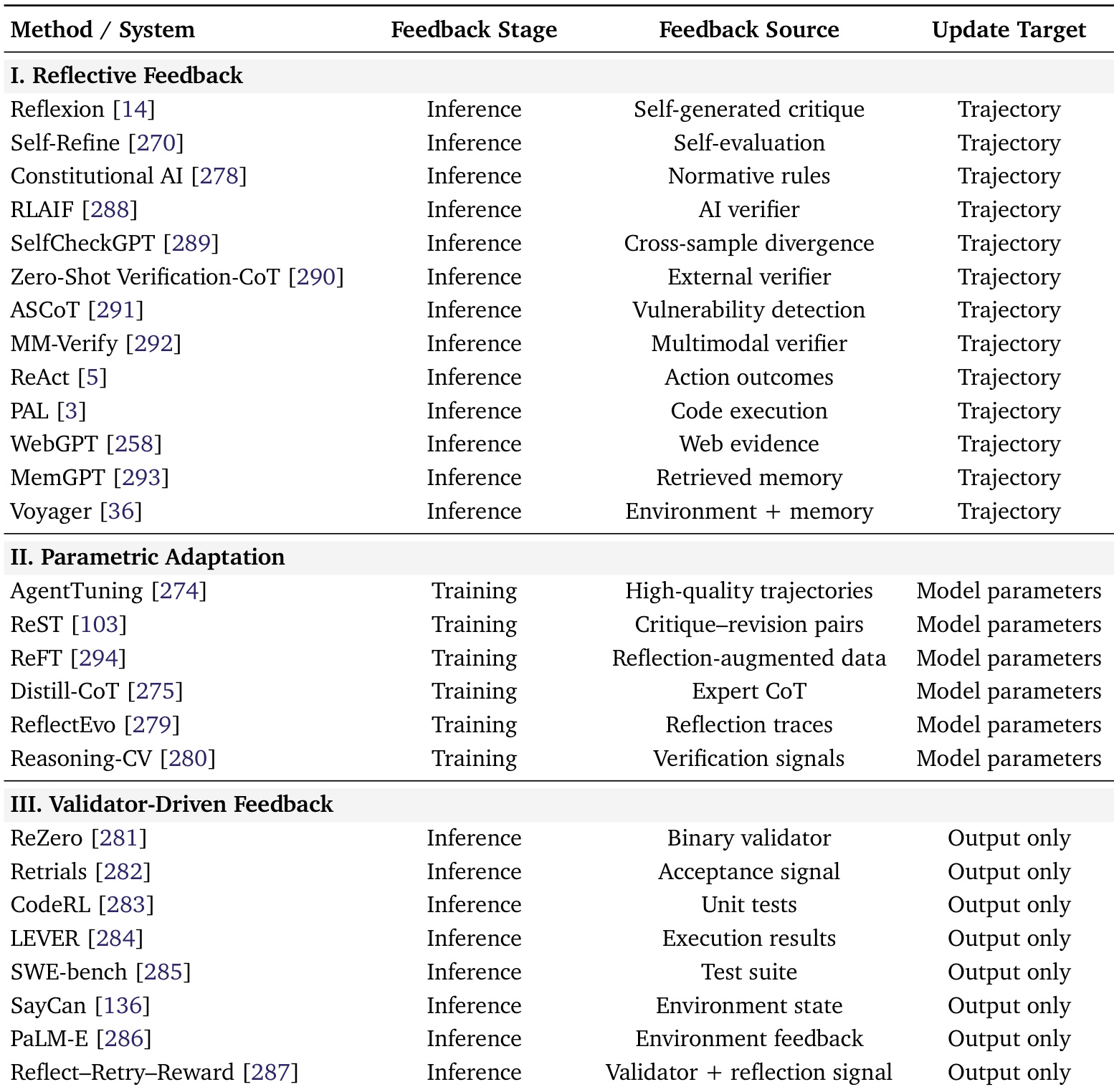

Building upon this foundation, the self-evolving layer, described in Section 4, introduces mechanisms for the agent to improve its own capabilities over time. This is achieved through a feedback loop that enables the agent to reflect on its performance. The framework identifies three primary feedback regimes: reflective feedback, which allows the agent to revise its reasoning during inference; parametric adaptation, which updates the model's parameters through supervised or reinforcement learning; and validator-driven feedback, which uses external signals (e.g., success/failure) to guide resampling. This layer also encompasses self-evolving memory, where the agent's memory is not static but is actively managed and updated, allowing it to learn from past experiences and adapt its strategies.

The system's capabilities are further extended through collective multi-agent reasoning, as outlined in Section 5. This involves distributing tasks among specialized agents, each with a distinct role such as a leader, worker, or critic. This role-based collaboration allows for the decomposition of complex problems and the coordination of actions, enabling the system to tackle tasks that are beyond the scope of a single agent. The framework also highlights the application of these core reasoning abilities across various domains, including robotics, healthcare, finance, and scientific discovery, demonstrating the versatility of the agentic paradigm. The authors' approach unifies these diverse capabilities under a single control-theoretic framework, providing a systematic and scalable architecture for building advanced, autonomous AI systems.

Experiment

- Post-training planning methods validate reward design and optimal control via RL or control theory, with systems like Reflexion, Reflect then-Plan, and Rational Decision Agents using utility-based learning to guide behavior.

- Reward modeling and shaping are applied in works [189, 190], while optimal control is explicitly addressed in [191–194], and trajectory optimization via diffusion models appears in [195–197].

- Offline RL approaches [119, 198, 147] use pretrained dynamics or cost models to optimize planning, complementing symbolic or heuristic methods by operating over continuous or learned reward spaces.

The authors use a table to categorize tool-use optimization systems into three feedback types: reflective, parametric adaptation, and validator-driven feedback. Results show that reflective methods primarily rely on inference-stage feedback from self-generated or external sources to update trajectories, while parametric adaptation and validator-driven methods focus on training-stage or inference-stage feedback to adjust model parameters or output only.