Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

InkSight:視覚言語モデルに読むことと書くことを教えることで実現するオフラインからオンラインへの手書き文字変換

InkSight:視覚言語モデルに読むことと書くことを教えることで実現するオフラインからオンラインへの手書き文字変換

概要

デジタルノート記録は、ベクタ形式で保存可能な耐久性・編集性・検索しやすさを備えた、いわゆる「デジタルインク」として知られる手法として注目を集めている。しかし、こうしたデジタル記録法と、依然として大多数のユーザーに支持されている伝統的な筆記用紙によるノート記録との間に、依然として大きなギャップが存在している。本研究では、InkSightという手法を通じて、物理的な手書き(オフラインでの手書き)を、自然な形でデジタルインク(オンラインでの手書き)に変換できるようにすることを目指しており、このプロセスを「デレンダリング」と呼ぶ。これまでの研究は、画像の幾何学的特性に焦点を当てており、訓練データの領域外への一般化能力に限界があった。一方、本手法は「読む」ことと「書く」ことに関する事前知識を組み合わせることで、取得が困難な大量のペアデータがなくてもモデルを学習可能にしている。知られている限り、本研究は任意の写真において多様な視覚的特徴や背景を持つ手書き文字を効果的にデレンダリングする初めての試みである。さらに、訓練データの範囲を超えて単純なスケッチにも一般化可能である。人間による評価の結果、難易度の高いHierTextデータセット上で生成されたサンプルの87%が入力画像の有効なトレースとして評価され、そのうち67%は人間がペンで描いた軌跡と見なされた。

One-sentence Summary

The authors, from Google DeepMind and EPFL, propose InkSight, a vision-language model that derenders offline handwriting from arbitrary photos into realistic digital ink trajectories by combining reading and writing priors, enabling generalization beyond training domains without large paired datasets, with applications in digital note-taking and sketch conversion.

Key Contributions

- InkSight is the first system to perform derendering—converting arbitrary photos of handwritten text into digital ink—by leveraging vision-language models to integrate reading and writing priors, enabling robust performance without requiring large amounts of paired training data.

- The method achieves state-of-the-art generalization across diverse handwriting styles, backgrounds, and even simple sketches, with human evaluation showing 87% of outputs are valid tracings of input images and 67% resemble human pen trajectories.

- The approach uses a simple yet effective architecture combining a ViT encoder and mT5 encoder-decoder, and is made publicly available with a released model, generated inks in inkML format, and expert-traced data to support future research.

Introduction

The authors leverage vision-language models to address the challenge of converting offline handwriting—photos of handwritten notes—into digital ink, a process known as derendering. This capability bridges the gap between traditional pen-and-paper note-taking and modern digital workflows, enabling users to preserve the natural feel of handwriting while gaining editability, searchability, and integration with digital tools. Prior work relied heavily on geometric priors and handcrafted heuristics, limiting generalization to specific scripts, clean backgrounds, or controlled conditions, and suffered from a lack of paired training data. The main contribution is a novel, data-efficient approach that combines learned reading and writing priors through a multi-task training setup, allowing the model to infer stroke order and spatial structure without requiring large-scale paired datasets. The system uses a simple architecture based on ViT and mT5, processes input images via OCR-guided word segmentation, and generates semantically and geometrically accurate digital ink sequences. It demonstrates strong performance across diverse handwriting styles, complex backgrounds, and even simple sketches, with human evaluations showing high fidelity to real pen trajectories. The authors release a public model and dataset to support future research.

Dataset

- The dataset comprises two main components: public and in-house collections for both OCR (text image) and digital ink (pen trajectory) data.

- Public OCR training data includes RIMES, HierText, IMGUR5K, ICDAR'15 historical documents, and IAM, with word-level crops extracted where possible, resulting in 295,000 Latin-script samples.

- Public digital ink data comes from VNOOnDB, SCUT-Couch, and DeepWriting; DeepWriting is split into character-, word-, and line-level crops, and VNOOnDB provides individual word-level inks, totaling approximately 2.7 million samples.

- In-house OCR data contains ~500,000 samples, primarily handwritten (67%) and printed (33%), with 95% labeled in English. In-house digital ink data contains ~16 million samples, with Mandarin (37%) and Japanese (23%) as the dominant languages.

- All OCR training data is filtered to ensure images are at least 25 pixels on each side, with aspect ratios between 0.5 and 4.0 to ensure suitability for 224×224 rendering.

- Digital ink is preprocessed via resampling at 20 ms intervals, Ramer-Douglas-Peucker simplification to reduce stroke length, and normalization to center strokes on a 224×224 canvas with coordinates scaled to [0, 224].

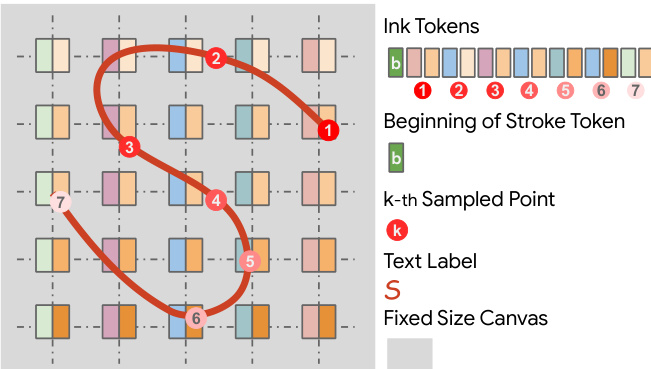

- Ink is tokenized into discrete tokens: a start-of-stroke token followed by separate x and y coordinate tokens, each rounded to integers, using a vocabulary of 2N + 3 = 451 tokens (N = 224).

- The full token set combines the multilingual mT5 tokenizer (approx. 20k tokens) with the 451 ink-specific tokens, enabling joint text and ink modeling while reducing model size by ~80%.

- For derendering training, digital ink samples are rendered into 224×224 images using the Cairo graphics library, with random augmentations including rotation, stroke and background color, stroke width, background noise, grids, and box blur.

- Rendering and augmentation are designed to simulate real-world variability, with no performance gains observed from perspective skew, shifting, or scaling.

- The model is trained on a mixture of OCR and digital ink data, with training splits derived from public and in-house datasets, and mixture ratios optimized for derendering and recognition tasks.

- Evaluation uses test splits from IAM (~17.6k), IMGUR5K (~23.7k), and filtered HierText (~1.3k handwritten words), with a small human-annotated golden set of ~200 traced samples from HierText used for reference and human evaluation.

Method

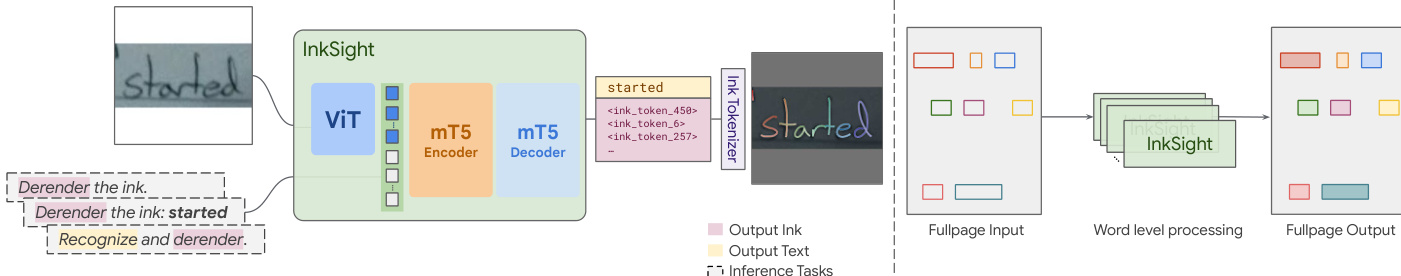

The authors leverage a hybrid vision-language model architecture, named InkSight, designed for digital ink understanding and generation. The framework integrates a Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder with an mT5 encoder-decoder Transformer model. The ViT encoder, initialized with pre-trained weights, processes the input image to extract visual features. These features are then fed into the mT5 encoder-decoder, which generates the output based on the provided task-specific instructions. The model uses a unified token vocabulary that includes both standard mT5 character tokens and specialized tokens for ink representation, enabling it to handle both text and ink outputs. During training, the ViT encoder weights are frozen, while the mT5 encoder-decoder is trained from scratch to adapt to the custom token set. This design allows the model to perform multiple tasks, including derendering ink from images, recognizing text, and generating ink from text, all within a single unified framework.

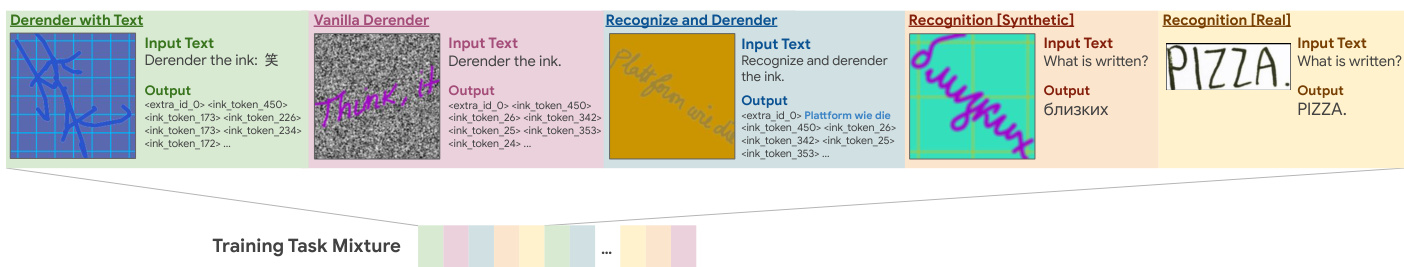

The training process employs a multi-task mixture to enhance generalization and robustness. As shown in the figure below, the training mixture consists of five distinct task types: two derendering tasks (producing ink output), two recognition tasks (producing text output), and one mixed task (producing both text and ink output). Each task is defined by a specific input text prompt that guides the model's behavior during both training and inference. This setup enables the model to learn diverse capabilities, such as generating realistic ink strokes from images, recognizing text in images, and combining both tasks in a single inference step. The tasks are shuffled and assigned equal probability during training, ensuring balanced learning across all objectives.

To represent ink in the model, a fixed-size canvas is used, where each position corresponds to a token. The ink tokens are organized into a sequence that captures the spatial and temporal order of strokes. The beginning of a stroke is marked by a special token, and subsequent points along the stroke are represented by indexed tokens, with the k-th sampled point indicated by a token labeled with k. Text labels are also embedded within this token sequence, allowing the model to associate ink strokes with their corresponding text content. This tokenization scheme enables the model to process and generate ink in a structured manner, preserving the spatial relationships between strokes and text.

Experiment

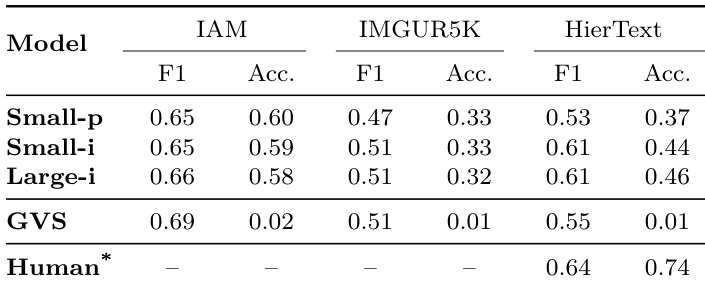

- Large-i model outperforms GVS and smaller variants on HierText, achieving higher similarity to real digital inks and better handling of diverse styles, occlusions, and complex backgrounds; on IAM and IMGUR5K, models perform similarly to GVS but show improved robustness with larger scale.

- Human evaluation on 200 HierText samples shows Large-i achieves the highest proportion of "good tracing" and "human-like" ratings, with performance improving as model and data scale up; common errors include missing details, extra strokes, and double tracing.

- Automated evaluation confirms model ranking aligns with human judgment: Large-i achieves the highest Character Level F1 score on HierText (0.58) and superior Exact Match Accuracy in online handwriting recognition (up to 78.2%) compared to GVS (near 0%), demonstrating strong semantic and geometric fidelity.

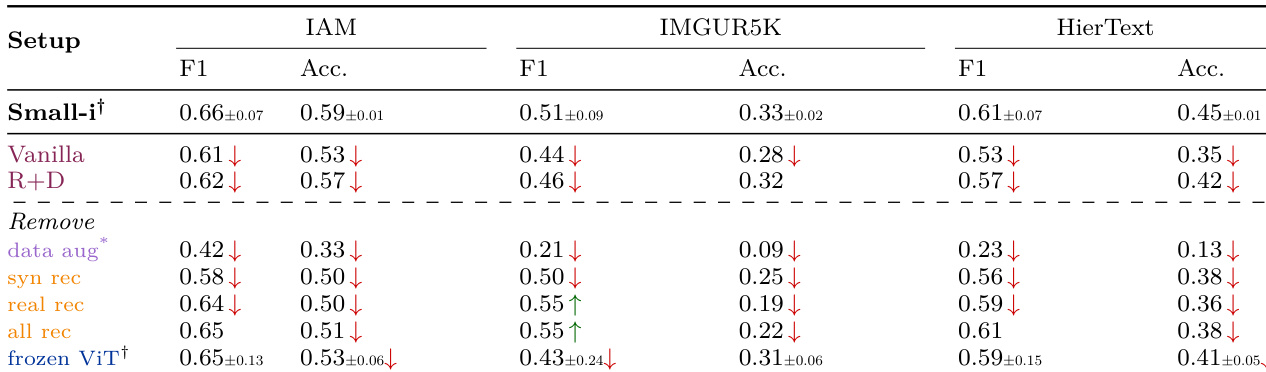

- Training with recognition tasks and data augmentation significantly improves derendering quality and semantic consistency; removing recognition tasks reduces accuracy and increases noise misinterpretation, while unfreezing ViT leads to instability and overfitting to background noise.

- Models generalize to out-of-domain inputs such as sketches and multilingual text (e.g., Korean, French), though performance degrades on unseen scripts; Large-i shows better robustness than Small-p due to broader training data.

- Derendered inks from IAM train set, when used to train an online handwriting recognizer, achieve competitive CER performance (especially when combined with real inks), proving offline datasets can effectively augment online recognizer training.

- Inference with text input (Derender with Text) enhances semantic consistency, especially on ambiguous inputs, while Vanilla Derender is more robust to noise but less semantically accurate; a fallback mechanism mitigates task confusion during decoding.

The authors compare the performance of models trained on derendered inks versus real inks for online handwriting recognition, using Character Error Rate (CER) as the metric. Results show that models trained on derendered inks achieve slightly higher CER than those trained on real inks, but combining both data types significantly reduces CER, demonstrating that derendered inks can effectively augment real data for training.

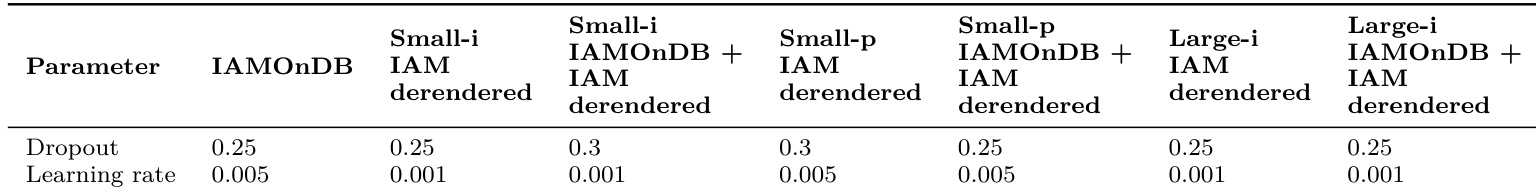

The authors use different dropout and learning rate values for their model variants across datasets, with Small-i and Large-i models using a lower learning rate of 0.001 and a dropout of 0.25 on IAMOnDB, while Small-p models use a higher learning rate of 0.005 and a dropout of 0.3 when trained on IAMOnDB plus IAM derendered data. Results show that the choice of hyperparameters varies depending on the model size and training data, with larger models generally using more conservative learning rates and dropout values.

The authors use Table 3 to conduct an ablation study on the Small-i model, examining the impact of different inference tasks and design choices. Results show that using the Derender with Text task improves performance over other inference modes, and removing data augmentation or recognition tasks significantly degrades results across all datasets.

Results show that the Large-i model achieves the highest Character Level F1 score on the HierText dataset, outperforming both Small-p and Small-i, while all models perform similarly on the IAM dataset. The GVS baseline matches or exceeds the models on IAM but fails to generalize to more complex datasets, as evidenced by its near-zero accuracy on HierText.

The authors compare the performance of an online handwriting recognizer trained on real digital inks from IAMOnDB, on derendered inks from IAM, and on a combination of both. Results show that training on the combined dataset achieves a lower Character Error Rate (4.6%) compared to using only real inks (6.1%) or only derendered inks (7.8%), indicating that derendered inks can effectively augment real data for improved recognition.