Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

Building Production-Ready Probes For Gemini

Building Production-Ready Probes For Gemini

János Kramár Joshua Engels Zheng Wang Bilal Chughtai Rohin Shah Neel Nanda Arthur Conmy

Abstract

Frontier language model capabilities are improving rapidly. We thus need stronger mitigations against bad actors misusing increasingly powerful systems. Prior work has shown that activation probes may be a promising misuse mitigation technique, but we identify a key remaining challenge: probes fail to generalize under important production distribution shifts. In particular, we find that the shift from short-context to long-context inputs is difficult for existing probe architectures. We propose several new probe architectures that handle this long-context distribution shift.We evaluate these probes in the cyber-offensive domain, testing their robustness against various production-relevant distribution shifts, including multi-turn conversations, long context prompts, and adaptive red teaming. Our results demonstrate that while our novel architectures address context length, a combination of architecture choice and training on diverse distributions is required for broad generalization. Additionally, we show that pairing probes with prompted classifiers achieves optimal accuracy at a low cost due to the computational efficiency of probes.These findings have informed the successful deployment of misuse mitigation probes in user-facing instances of Gemini, Google's frontier language model. Finally, we find early positive results using AlphaEvolve to automate improvements in both probe architecture search and adaptive red teaming, showing that automating some AI safety research is already possible.

One-sentence Summary

Google DeepMind researchers propose novel activation probe architectures—specifically MultiMax and Max of Rolling Means Attention Probes—that significantly improve generalization to long-context inputs, a key challenge in production misuse mitigation for frontier language models. By combining architectural innovations with training on diverse distributions and cascading with prompted classifiers, the approach achieves near-LLM accuracy at a fraction of the cost, enabling successful deployment in user-facing Gemini instances. The work further demonstrates that automated search via AlphaEvolve can discover high-performing probe designs, indicating early feasibility of automating AI safety research.

Key Contributions

- Existing activation probes fail to generalize under critical production distribution shifts, particularly when transitioning from short-context to long-context inputs, limiting their effectiveness as misuse mitigations in real-world deployments.

- The authors introduce the MultiMax probe architecture and demonstrate its superior performance on long-context data, while automated architecture search via AlphaEvolve discovers a probe variant that outperforms baselines with high statistical confidence.

- A cascading classifier that combines probes with a large language model achieves lower false negative rates than the LLM alone while using less than 10% of its inference cost, enabling efficient and robust misuse detection in production.

Introduction

Frontier language models like Gemini face growing risks of misuse, particularly in cyber-offensive domains, where malicious users can exploit model capabilities through adversarial prompts. To address this, activation probes—lightweight models trained on internal hidden states—have emerged as a cost-effective alternative to expensive language model classifiers for real-time input monitoring. However, prior probe architectures struggle to generalize under key production distribution shifts, especially long-context inputs, due to memory and computational constraints that make training on such data prohibitively costly. The authors identify this fragility as a critical limitation, as probes trained on short contexts fail when faced with extended or multi-turn interactions, undermining their reliability in real-world deployment. Their main contribution is a systematic investigation of four strategies to improve probe robustness: introducing a new MultiMax probe architecture that enhances long-context performance, leveraging AlphaEvolve for automated probe architecture search, implementing a cascading classifier that uses a language model only when the probe is uncertain to achieve high accuracy at low cost, and demonstrating that training across multiple random seeds can reduce variance and improve generalization. These advances enabled the successful deployment of probes in production Gemini systems, achieving performance comparable to full language models while using a fraction of the compute, though challenges remain in defending against adaptive, evolving attacks.

Dataset

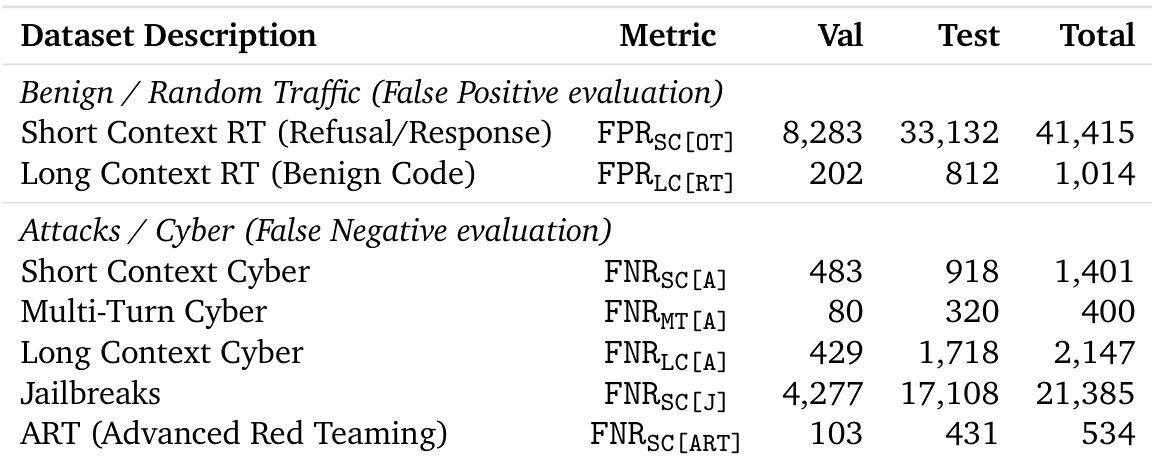

- The dataset comprises multiple sources focused on cyber misuse, divided into training, validation, and test splits with no prompt overlap across sets.

- Training data includes a mix of benign and malicious cyber prompts, excluding long-context examples to reduce computational burden.

- Validation and test sets are designed to represent distribution shifts from training data, ensuring robust evaluation of generalization.

- The test sets include long-context data, with strict filtering to prevent data leakage: 1,711 long-context rows matching short-context training data were removed, leaving 436 clean rows for evaluation.

- The authors use a weighted error metric to set the optimal threshold τ*, assigning higher weights to overtriggering false positives (weight 50), followed by false negatives (weight 5), and hard negative false positives (weight 2).

- This weighting prioritizes minimizing false positives on benign, non-cyber data—such as PII-redacted traffic, capability evaluation data, and unrelated synthetic prompts—reflecting the high cost of overtriggering.

- The final test loss is computed as a weighted average of FPRs and FNRs across all test datasets, used as the primary metric for method comparison.

- Activations for probe training are stored on disk using TPU machines, enabling faster iteration with single-layer probes; CPU workers are used for evaluation, especially for long-context data that exceeds single-node memory.

- A custom data loading pipeline with round-robin batch allocation and optimizations for padding and pipelining enables stable long-context probe training with smaller batch sizes and improved accelerator utilization.

Method

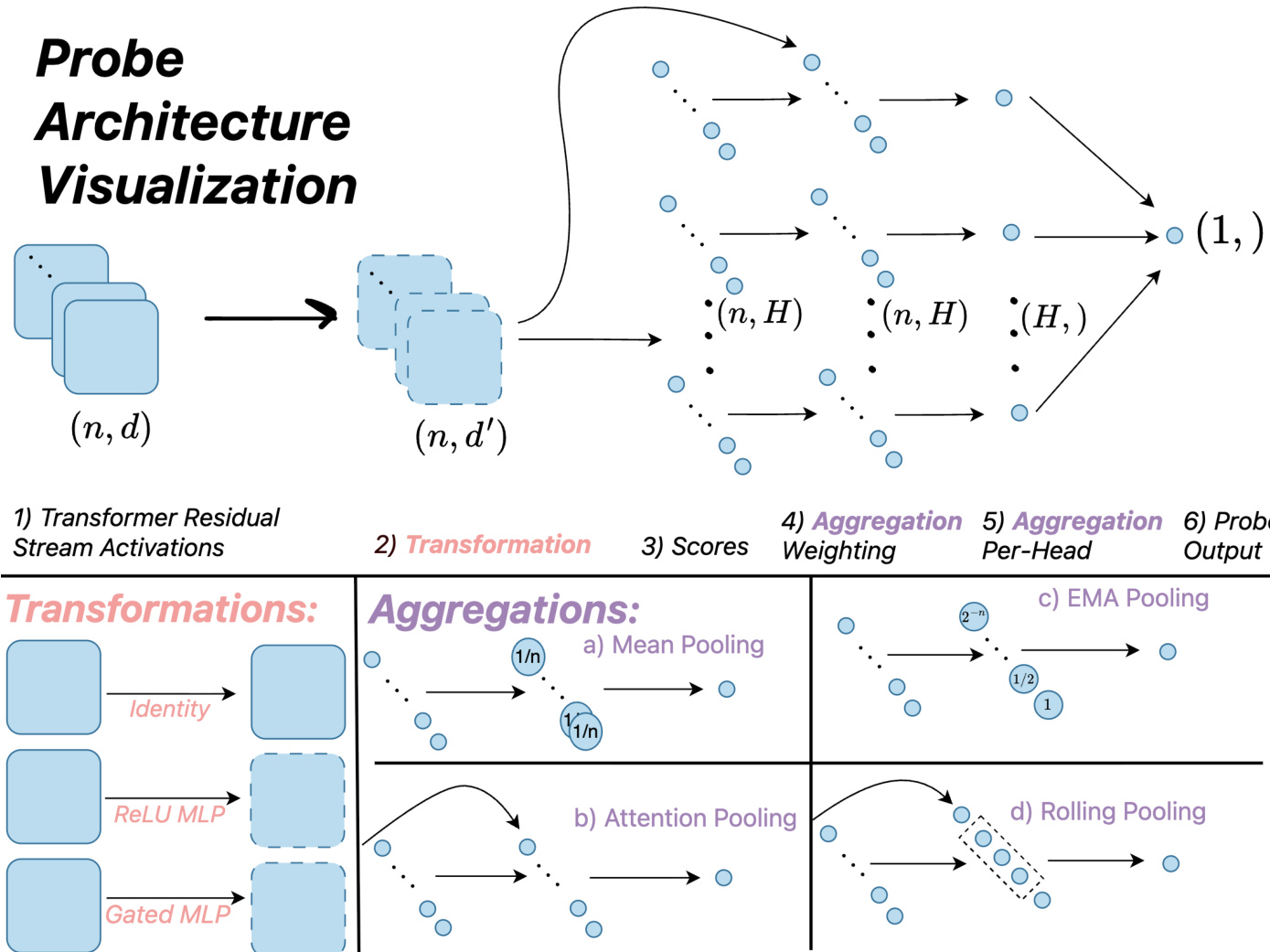

The authors leverage a modular framework for designing and evaluating probe architectures that classify token sequences based on hidden states extracted from a deployed language model. The overall process begins with extracting residual stream activations from a fixed intermediate layer of the language model, resulting in a sequence of token-level representations of shape (n,d), where n is the sequence length and d is the hidden dimension. These activations serve as input to a probe, which processes them through a series of transformations and aggregations to produce a scalar classification score.

Refer to the framework diagram  . The architecture follows a six-step pipeline: (1) Transformer Residual Stream Activations, (2) Transformation per-position, (3) Scores, (4) Aggregation Weighting, (5) Aggregation Per-Head, and (6) Probe Output. The transformation step applies a function to each token's activation, producing a transformed representation of shape (n,d′). This step includes identity mapping for linear probes, ReLU-based MLPs for mean-pooled MLP probes, and gated MLPs for more complex architectures. The scores are then computed, typically as a linear projection of the transformed activations.

. The architecture follows a six-step pipeline: (1) Transformer Residual Stream Activations, (2) Transformation per-position, (3) Scores, (4) Aggregation Weighting, (5) Aggregation Per-Head, and (6) Probe Output. The transformation step applies a function to each token's activation, producing a transformed representation of shape (n,d′). This step includes identity mapping for linear probes, ReLU-based MLPs for mean-pooled MLP probes, and gated MLPs for more complex architectures. The scores are then computed, typically as a linear projection of the transformed activations.

Aggregation is the core mechanism for reducing the sequence of token-level representations to a single scalar score. The framework supports multiple aggregation strategies. For instance, mean pooling computes the average of the scores across the sequence, while exponential moving average (EMA) aggregation applies a recursive update to maintain a running average of the scores. Attention-based aggregation computes a weighted average of the scores, where the weights are derived from a learned query vector and the transformed activations, enabling the probe to focus on relevant tokens. The authors also introduce a rolling pooling strategy, where attention is computed within sliding windows of fixed size, and the maximum of these window-level scores is taken as the final output.

The authors compare several probe architectures, including baseline methods such as linear probes, EMA probes, and MLP probes, as well as their novel designs. Linear probes apply a simple linear transformation and mean pooling. EMA probes refine the linear probe by applying an exponential moving average to the scores at inference time. MLP probes use a multi-layer perceptron to transform the activations before pooling. The authors propose two novel architectures: MultiMax probes, which replace the softmax weighting in attention probes with a hard max operation to prevent signal dilution in long contexts, and the Max of Rolling Means Attention Probe, which combines attention within sliding windows and takes the maximum of the window-level outputs. These architectures are designed to improve generalization to long contexts and reduce overtriggering. The framework also supports cascading classifiers, where a fast probe is used for initial classification, and a more expensive language model is invoked only when the probe is uncertain, enabling a cost-accuracy tradeoff.

Experiment

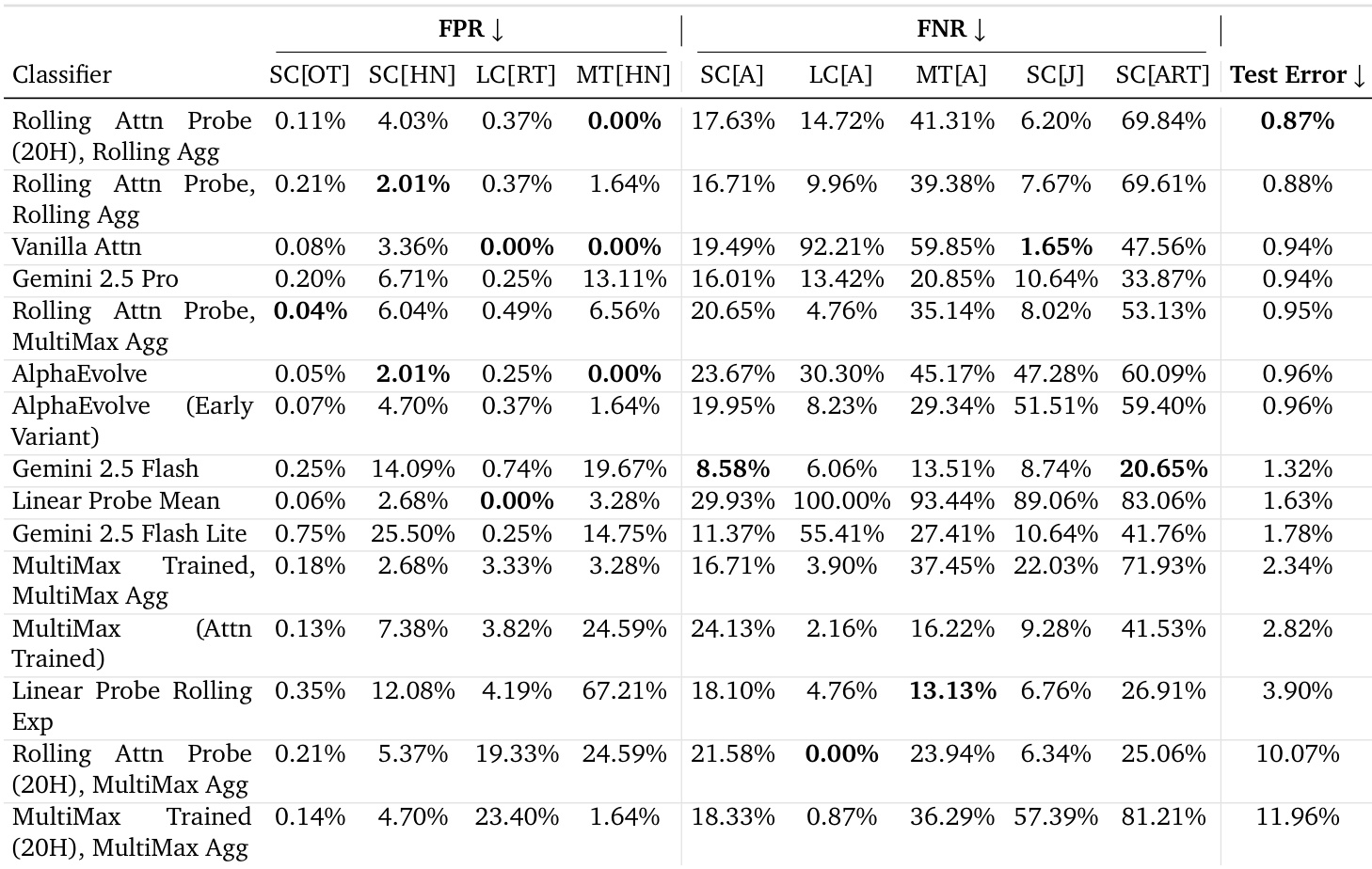

- AlphaEvolve was used to discover novel probing architectures, with two top-performing variants—MultiMax and Max of Rolling Mean Attention Probes—outperforming existing baselines, including linear and attention probes, on cyber-offensive query detection.

- On the main evaluation dataset, the Max of Rolling Means Attention Probe with MultiMax aggregation achieved a test error of 2.53%, surpassing the Linear Probe Mean (0.064 test loss) and outperforming all LLMs, with statistically significant gains confirmed via bootstrap resampling (Table 4).

- Architecture choice provides a much larger performance gain than seed selection: best architecture achieves 0.025 test loss vs. median seed selection gain of 0.003, and a 0.109 AUROC gap between best and worst architectures on auxiliary datasets.

- AlphaEvolve closed approximately 50% of the test error gap between the baseline attention probe and optimal performance, with both early and final discovered architectures achieving high median AUROC (0.975) across diverse datasets.

- Probes trained on short-context data matched or exceeded the performance of models trained on long-context data (2.38% vs. 2.53% test error), demonstrating that architectural improvements can overcome data limitations.

- Cascading classifiers combining the best probe with Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite achieved superior cost-accuracy trade-offs, with Flash-Lite outperforming Pro across the entire frontier due to lower cost and comparable accuracy.

- Seed selection improves performance modestly (average test loss reduction of 0.008), but architecture search is far more impactful, suggesting practitioners should prioritize architecture over extensive seed tuning.

The authors use the table to detail the composition of their evaluation datasets, specifying the number of test and total samples for each dataset across different cyber and benign traffic categories. The table shows that the datasets vary significantly in size, with the Short Context RT (Refusal/Response) dataset having the largest test set at 33,132 samples, while the ART (Advanced Red Teaming) dataset has the smallest at 431 test samples.

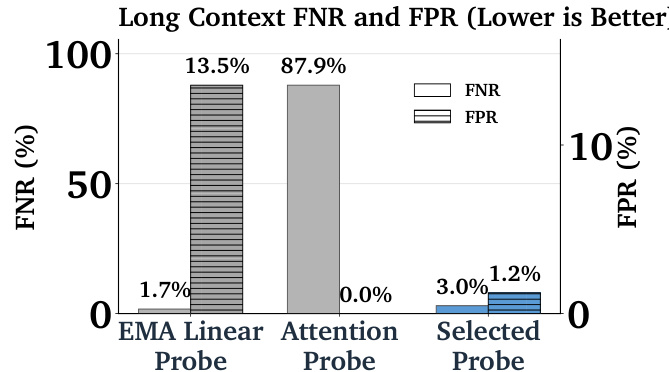

The authors compare the long-context generalization performance of different probe architectures, showing that the EMA Linear Probe achieves a low false positive rate of 1.7% but a high false negative rate of 13.5%. In contrast, the Attention Probe has a false positive rate of 0.0% but a false negative rate of 87.9%, while the Selected Probe achieves a balanced performance with 3.0% false negative rate and 1.2% false positive rate.

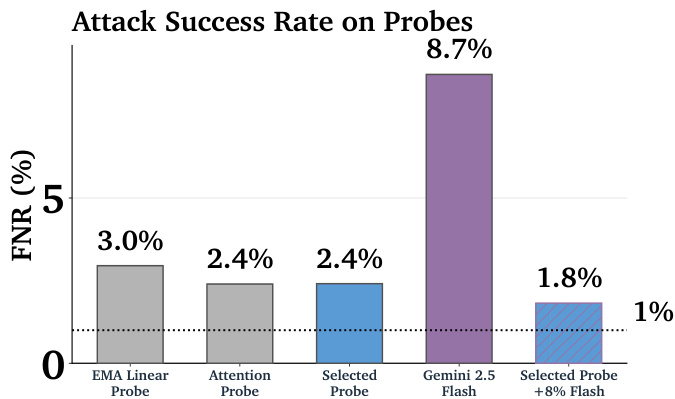

The authors use a bar chart to compare the false negative rates (FNR) of various probes and language models on adversarial attacks. Results show that the Gemini 2.5 Flash model has the highest attack success rate at 8.7%, significantly outperforming all probes. The Selected Probe achieves a 1.8% FNR, demonstrating that the best-performing probe still leaves a substantial vulnerability to attack, though it is much lower than the LLM's rate.

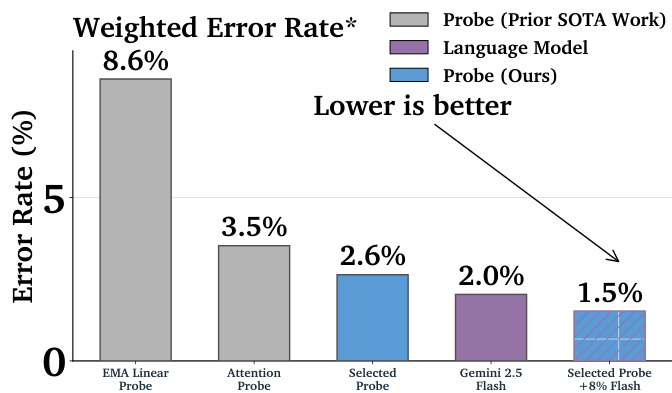

The authors compare the weighted error rates of different probe and language model classifiers, showing that their selected probe achieves a 2.6% error rate, which is lower than the 3.5% error rate of the attention probe and the 8.6% error rate of the EMA linear probe. The best-performing configuration, combining the selected probe with Gemini 2.5 Flash, reduces the error rate further to 1.5%, demonstrating significant improvements over prior methods.

The authors use AlphaEvolve to generate novel probing architectures, with the best-performing variants significantly outperforming existing linear probe baselines across multiple datasets. Results show that the top architectures, including AlphaEvolve's MultiMax variation and the Max of Rolling Mean Attention Probe, achieve lower test error than all prior methods, though no single method dominates across all distribution shifts.