Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

Dream2Flow: Bridging Video Generation and Open-World Manipulation with 3D Object Flow

Dream2Flow: Bridging Video Generation and Open-World Manipulation with 3D Object Flow

Karthik Dharmarajan Wenlong Huang Jiajun Wu Li Fei-Fei Ruohan Zhang

Abstract

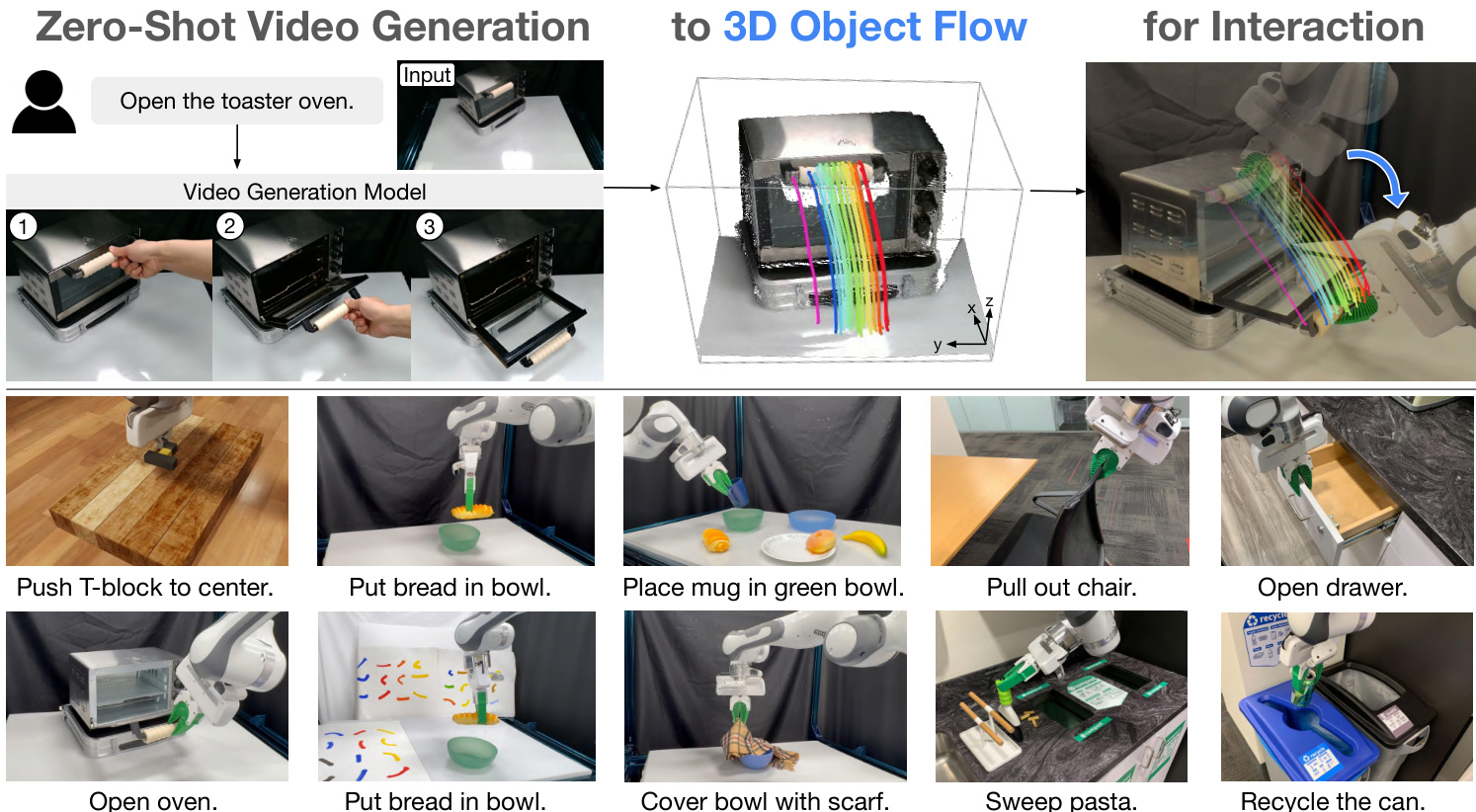

Generative video modeling has emerged as a compelling tool to zero-shot reason about plausible physical interactions for open-world manipulation. Yet, it remains a challenge to translate such human-led motions into the low-level actions demanded by robotic systems. We observe that given an initial image and task instruction, these models excel at synthesizing sensible object motions. Thus, we introduce Dream2Flow, a framework that bridges video generation and robotic control through 3D object flow as an intermediate representation. Our method reconstructs 3D object motions from generated videos and formulates manipulation as object trajectory tracking. By separating the state changes from the actuators that realize those changes, Dream2Flow overcomes the embodiment gap and enables zero-shot guidance from pre-trained video models to manipulate objects of diverse categories-including rigid, articulated, deformable, and granular. Through trajectory optimization or reinforcement learning, Dream2Flow converts reconstructed 3D object flow into executable low-level commands without task-specific demonstrations. Simulation and real-world experiments highlight 3D object flow as a general and scalable interface for adapting video generation models to open-world robotic manipulation. Videos and visualizations are available at https://dream2flow.github.io/.

One-sentence Summary

Researchers from Stanford University introduce Dream2Flow, a framework that bridges video generation and robotic control by extracting 3D object flow from generated videos as an intermediate representation. Unlike prior methods that mimic rigid human motions, Dream2Flow decouples the desired state change from the robot's specific embodiment, enabling zero-shot manipulation of diverse objects—including rigid, articulated, deformable, and granular types—using off-the-shelf video models and vision tools without task-specific demonstrations.

Key Contributions

- The paper addresses the challenge of using video generation models for open-world robotic manipulation, which often struggle with the embodiment gap between human motions and robot action spaces. It proposes that these models can be used as visual world models to predict physically plausible object interactions, separating the desired state changes from the specific actuators required.

- It introduces Dream2Flow, a novel method that uses 3D object flow as an intermediate interface to bridge video generation with robot control. The approach reconstructs 3D object trajectories from generated videos using depth estimation and point tracking, providing a clear tracking goal that is independent of the robot's embodiment.

- The authors demonstrate an autonomous pipeline that generates a task video, extracts the 3D object flow, and synthesizes robot actions via trajectory optimization or reinforcement learning. This method effectively leverages the rich priors of video models to guide manipulation without directly mimicking human actions, cleanly separating the "what" from the "how" of a task.

Introduction

The authors address the challenge of specifying robotic manipulation tasks, where prior methods range from rigid symbolic formalisms to complex learning-based policies. Specifying tasks with natural language is more intuitive but can be ambiguous, while vision-language-action models are often tied to specific robot embodiments. To overcome these issues, the authors introduce Dream2Flow, a method that uses video generation models to create a visual plan. They leverage these models to generate a video from an initial image and a language instruction, then extract 3D object flow from this video to represent the desired object motion. This 3D flow serves as a robust, embodiment-agnostic interface for planning precise manipulation actions. However, the method is currently limited by its rigid-grasp assumption, a reliance on single-view video which struggles with occlusions, and long processing times.

Dataset

Dataset Composition and Sources

The dataset consists of video-language data for a diverse set of manipulation tasks, including "Push-T", "Open Door", and several "In-the-Wild" tasks like "Pull Out Chair" and "Sweep Pasta".

- Task Prompts: Task descriptions are provided as text prompts. For the "In-the-Wild" tasks, these include specific success criteria, such as moving a chair at least 5cm or opening a drawer to 90% of its full extension.

- Data Generation: The authors use generative video models, such as Veo 3 and Kling 2.1, to create the video data from these prompts.

- Robustness and Special Phrasing: To improve robustness, prompts include variations, for instance, replacing "bread" with "donut". To guide the generative models, prompts include phrases like "by one hand" to help with grasp selection and "the camera holds a still pose" to minimize camera motion, which is crucial for the downstream depth estimation pipeline.

Key Details for Subsets

- Push-T Task:

- Source: Generated using text prompts and a goal image that shows the start and end positions of the T-block.

- Filtering: The Veo 3 model was excluded from experiments for this task because it does not support end-frame inputs, a requirement for generating accurate motion for this specific task.

- Open Door Task:

- Source: Generated from a text prompt for a simulated environment.

- Processing: The prompt specifies that the action is performed without a hand and that the camera remains still. For Kling 2.1, a relevance value of 0.7 and a negative prompt are added to the generation process.

- In-the-Wild Tasks:

- Source: This subset includes four distinct tasks: "Pull Out Chair", "Open Drawer", "Sweep Pasta", and "Recycle Can".

- Composition: Each task is defined by a specific object and goal, such as pushing pasta into a compost bin with a brush or placing a can into a recycling bin.

Data Usage and Processing

The authors use this generated dataset to train their model, Dream2Flow.

- Training Split: The data is used for the training split.

- Mixture Ratios: The paper does not specify mixture ratios for the different task data.

- Processing: The video data is processed to extract depth information, which relies on the "camera holds a still pose" condition in the prompts. The position of the hand in the video is also leveraged to help select the correct grasp on an object. For the "Push-T" task, a particle dynamics model is used, which takes feature-augmented particles as input to predict motion.

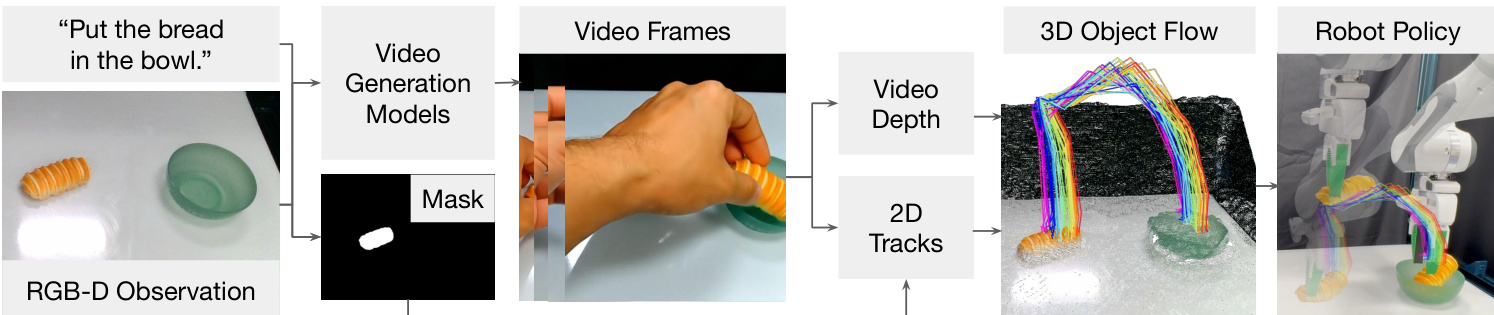

Method

The authors leverage a modular pipeline to bridge high-level visual predictions from off-the-shelf video generation models with low-level robot actions, enabling zero-shot open-world manipulation. The core idea is to extract 3D object flow—an intermediate representation of object motion—as a bridge between the visual imagination of a human-centric video model and the physical execution by a robot. This approach decouples the desired state changes in the environment from the specific embodiment and kinematic constraints of the robot.

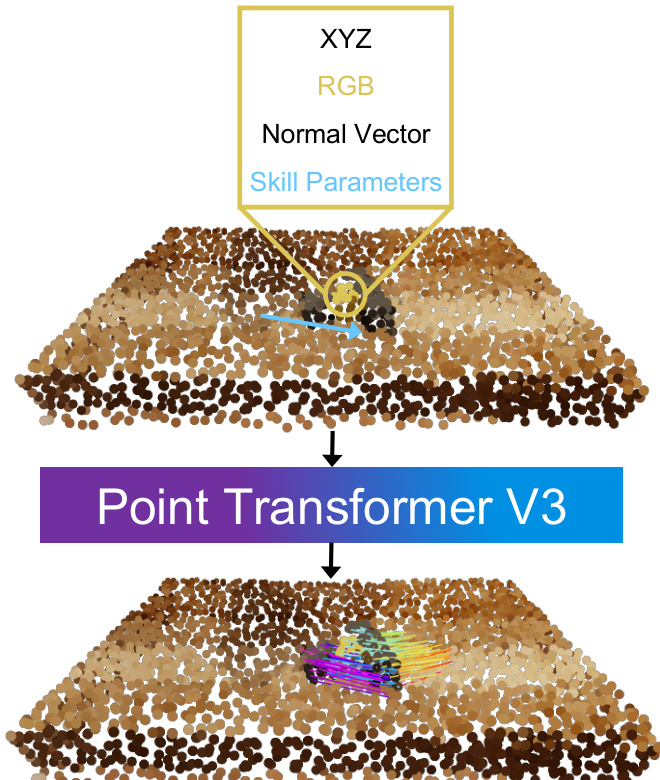

As shown in the figure below, the pipeline begins with a text-conditioned video generation model that synthesizes a sequence of frames depicting a human performing the requested task, given an initial RGB-D observation and a natural language instruction. The generated video is then processed to extract 3D object flow. This involves estimating per-frame depth using a monocular video depth estimator, which is calibrated to the robot’s initial depth observation to resolve scale ambiguity. Concurrently, the task-relevant object is localized using a grounding model, and a binary mask is generated. From this mask, a set of 2D points is sampled and tracked across the video using a point tracking model, producing 2D trajectories and visibility flags. These 2D tracks are lifted into 3D using the calibrated depth and camera intrinsics, resulting in a 3D object flow represented as a time-series of point trajectories in the robot’s coordinate frame.

The extracted 3D object flow serves as the target for action inference. The robot’s task is to manipulate the object such that its 3D point trajectories closely follow the generated flow. This is formulated as an optimization problem, where the objective is to minimize the sum of a task cost—measuring the distance between predicted object points and the target flow—and a control cost—penalizing undesirable robot motions such as joint limits violations or jerky movements. The dynamics model and action space vary depending on the domain. In simulated non-prehensile tasks like pushing, a learned particle-based dynamics model predicts the next state given a push skill parameterized by contact point, direction, and distance. In the real-world domain, the robot uses absolute end-effector poses as actions, and a rigid-grasp dynamics model assumes that the grasped part moves with the end-effector. For articulated tasks like door opening, a reinforcement learning policy is trained using the 3D object flow as a reward signal, guiding the robot to reproduce the desired motion across different embodiments.

The framework also includes specialized modules for robust execution. For grasp selection, the system uses a hand detection model to identify the thumb position in the generated video and selects the grasp closest to this position, ensuring the robot interacts with the same part of the object as the human in the video. For articulated objects, a filtering step identifies the movable part of the object by analyzing the average pixel displacement of tracked points, and a mask from a segmentation model is used to constrain the 2D flow to the movable part, preventing tracking errors on stationary components. The optimization process is further refined by using intermediate subgoals from the video flow, rather than only the final state, to guide replanning and avoid large rotational errors.

In the simulated Push-T domain, the system employs random shooting to sample multiple push parameters, predicts the resulting object motion using the learned dynamics model, and selects the action that minimizes the cost to the current subgoal. In the real-world setting, the optimization is performed using PyRoki, incorporating reachability, smoothness, and manipulability costs. The resulting end-effector trajectory is smoothed with a B-spline and executed using an inverse kinematics solver and a joint impedance controller. For the door opening task, the system trains a sensorimotor policy using Soft Actor-Critic, where the reward is derived from the 3D object flow, encouraging the robot to track the reference trajectory while staying near the object.

Experiment

- Dream2Flow as a video-control interface: The system was validated on five real-world and simulated manipulation tasks (e.g., Push-T, Open Oven). It demonstrates robustness to variations in object instances and backgrounds, and can adapt to different language goals within the same scene. However, real-world execution failures are primarily caused by video generation artifacts and tracking errors.

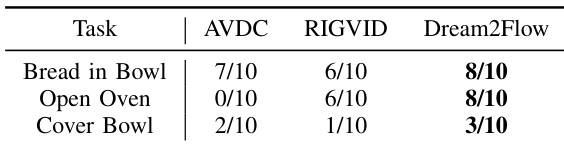

- Comparison to alternative interfaces: On real robot tasks, Dream2Flow outperforms AVDC and RIGVID. It handles deformable objects and partial occlusions more effectively by following 3D object flow rather than rigid transforms.

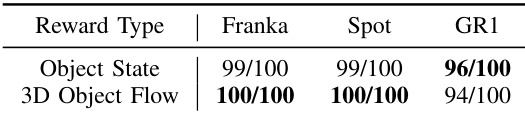

- 3D object flow as a policy reward: 3D object flow serves as an effective reward signal for training RL policies. Policies trained with this reward perform comparably to those using handcrafted state rewards across different robot embodiments (Franka Panda, Spot, GR1).

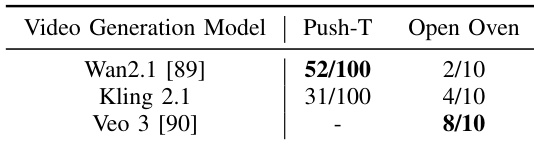

- Impact of the video model: Performance depends on the domain. Wan 2.1 excels in simulated tasks like Push-T, while Veo 3 performs best on real-world tasks like Open Oven. Other models can suffer from object morphing or incorrect articulation.

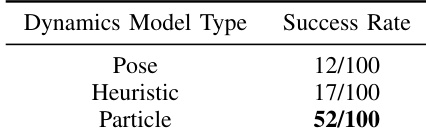

- Impact of the dynamics model: A particle-based dynamics model is crucial for success in tasks requiring rotation. It substantially outperforms alternative pose-based or heuristic models.

The authors compare Dream2Flow with two alternative video-based interfaces, AVDC and RIGVID, on three real-world tasks: Bread in Bowl, Open Oven, and Cover Bowl. Results show Dream2Flow outperforms both methods across all tasks, achieving 8/10 success in Bread in Bowl and Open Oven, and 3/10 in Cover Bowl, while AVDC and RIGVID exhibit lower success rates, particularly in tasks involving deformable objects or insufficient point visibility.

The authors evaluate the impact of different dynamics models on the Push-T task in simulation, comparing pose-based, heuristic, and particle-based models. Results show that the particle-based dynamics model achieves a success rate of 52/100, significantly outperforming the pose (12/100) and heuristic (17/100) models, demonstrating the importance of per-point predictions for accurately capturing object rotation and motion.

The authors evaluate the effectiveness of 3D object flow as a reward for training reinforcement learning policies across three different robot embodiments: Franka Panda, Spot, and GR1. Results show that policies trained with 3D object flow rewards achieve performance comparable to those trained with handcrafted object state rewards, with success rates of 100/100 for Franka and Spot, and 94/100 for GR1, indicating that 3D object flow can serve as a viable and generalizable reward signal for learning sensimotor policies.

The authors evaluate the impact of different video generation models on Dream2Flow’s performance in simulation and real-world tasks. Results show that Wan2.1 performs best on the simulated Push-T task with 52 out of 100 successes, while Veo 3 achieves the highest success rate on the real-world Open Oven task with 8 out of 10 successes, indicating that Veo 3 better captures physically plausible object trajectories in real-world settings.