Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

Adaptation of Agentic AI

Adaptation of Agentic AI

Abstract

Cutting-edge agentic AI systems are built on foundation models that can be adapted to plan, reason, and interact with external tools to perform increasingly complex and specialized tasks. As these systems grow in capability and scope, adaptation becomes a central mechanism for improving performance, reliability, and generalization. In this paper, we unify the rapidly expanding research landscape into a systematic framework that spans both agent adaptations and tool adaptations. We further decompose these into tool-execution-signaled and agent-output-signaled forms of agent adaptation, as well as agent-agnostic and agent-supervised forms of tool adaptation. We demonstrate that this framework helps clarify the design space of adaptation strategies in agentic AI, makes their trade-offs explicit, and provides practical guidance for selecting or switching among strategies during system design. We then review the representative approaches in each category, analyze their strengths and limitations, and highlight key open challenges and future opportunities. Overall, this paper aims to offer a conceptual foundation and practical roadmap for researchers and practitioners seeking to build more capable, efficient, and reliable agentic AI systems.

One-sentence Summary

The authors from UIUC, Stanford, Princeton, UC Berkeley, Caltech, UW, UCSD, Georgia Tech, Northwestern, TAMU, MGH, Keiji AI, and Unity propose a unified framework categorizing adaptation in agentic AI into four paradigms: agent adaptation with tool-execution or agent-output signals (A1/A2), and tool adaptation with agent-agnostic or agent-supervised signals (T1/T2). This framework clarifies the design space, highlights trade-offs in cost, flexibility, generalization, and modularity, and provides practical guidance for selecting strategies. The work demonstrates that T2-style agent-supervised tool adaptation enables data-efficient, modular, and generalizable system evolution, particularly through lightweight subagents that co-evolve with frozen foundation models, offering a scalable path toward robust, reliable, and efficient agentic systems across domains like deep research, software development, and drug discovery.

Key Contributions

- Agentic AI systems face challenges in reliability, long-horizon planning, and generalization, necessitating adaptation strategies that enhance performance and robustness through modifications to either the agent or its external tools.

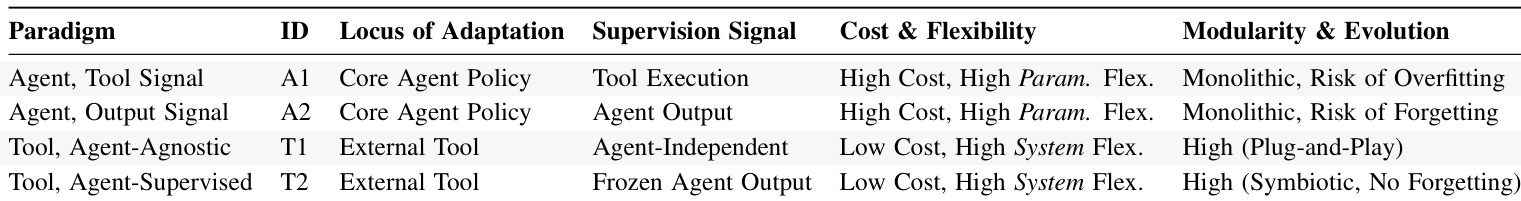

- The paper introduces a unified four-part framework categorizing adaptation into two dimensions—agent adaptation (A1: tool-execution-signaled, A2: agent-output-signaled) and tool adaptation (T1: agent-agnostic, T2: agent-supervised)—clarifying design trade-offs and guiding practical system design.

- The framework is supported by analysis of representative methods across domains, demonstrating that combining paradigms like T1 retrievers with A1 fine-tuning and T2 adaptive search agents enables more capable and efficient agentic systems.

Introduction

Agentic AI systems, built on foundation models like large language models, are designed to autonomously plan, reason, and interact with external tools to tackle complex, real-world tasks across domains such as scientific research, software development, and drug discovery. However, these systems often suffer from unreliable tool use, poor long-horizon planning, and limited generalization, especially in unexplored or dynamic environments. Prior work has addressed these issues through adaptation—modifying either the agent or its tools—but existing approaches lack a unified framework to clarify their design space, trade-offs, and interplay.

The authors introduce a systematic taxonomy that categorizes adaptation into four paradigms: A1 (agent adaptation using tool execution signals), A2 (agent adaptation using agent output signals), T1 (agent-agnostic tool adaptation), and T2 (agent-supervised tool adaptation). This framework explicitly maps the trade-offs between cost, flexibility, generalization, and modularity, showing that agent adaptation offers high flexibility but at high computational cost and risk of catastrophic forgetting, while tool adaptation enables efficient, modular upgrades without retraining the core agent. The authors further demonstrate how these paradigms are applied in practice—such as using T2-style search subagents to improve retrieval in RAG systems or A1-style closed-loop execution for code generation—and highlight their complementary nature.

The main contribution is a unified conceptual and practical roadmap that not only organizes the rapidly evolving field but also identifies key future directions: co-adaptation of agents and tools, continual adaptation in dynamic environments, safe adaptation to prevent reward hacking and unsafe exploration, and efficient adaptation via parameter-efficient and on-device methods. This framework enables researchers and practitioners to strategically combine adaptation strategies to build more capable, reliable, and scalable agentic systems.

Method

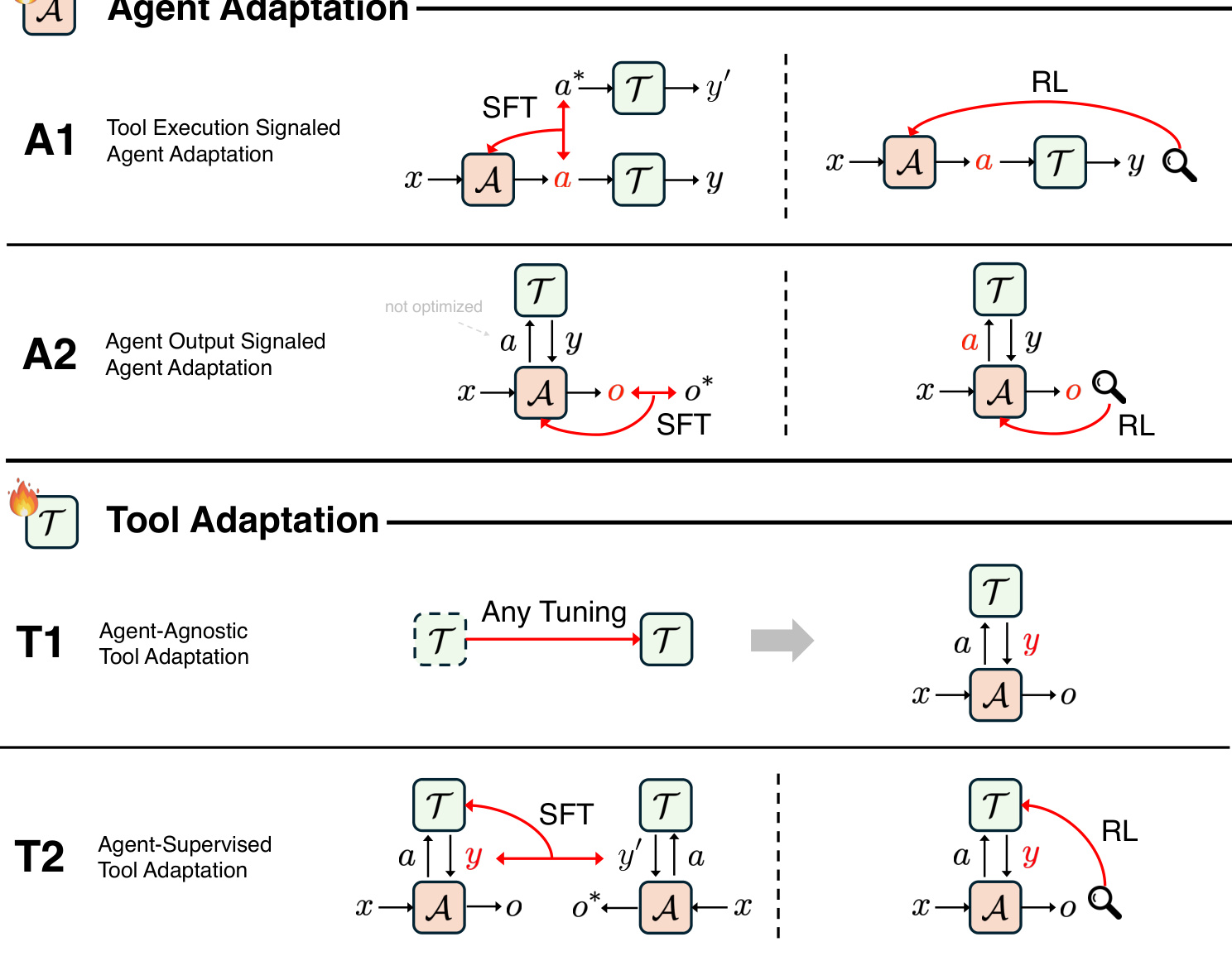

The paper presents a comprehensive framework for adapting agentic AI systems, categorizing adaptation approaches into four primary paradigms based on the optimization target and the source of the adaptation signal. This framework, illustrated in the conceptual diagram, divides the adaptation process into two main axes: agent-centric adaptation (A1, A2) and tool-centric adaptation (T1, T2). The core of the framework is the distinction between optimizing the agent's internal policy and optimizing the external tools that the agent interacts with.

The agent-centric paradigms, A1 and A2, both involve modifying the agent's parameters to improve its performance. The A1 paradigm, or "Tool Execution Signaled Agent Adaptation," focuses on optimizing the agent's ability to use tools correctly by leveraging direct feedback from the tool's execution. The adaptation signal is the verifiable outcome of the tool's action, such as the success of a code execution or the quality of a retrieved document. This approach is formalized as an optimization problem where the agent's policy is adjusted to maximize a reward function based on the tool's output. The A1 paradigm can be implemented through supervised fine-tuning (SFT) on successful tool-call trajectories or through reinforcement learning (RL), where the agent receives a scalar reward from the tool's execution result. In contrast, the A2 paradigm, or "Agent Output Signaled Agent Adaptation," optimizes the agent's overall strategy for using tools by using the quality of the agent's final output as the adaptation signal. The goal is to align the agent's final answer with correctness or quality criteria, which may depend on the integration of tool outputs. This paradigm also supports both SFT and RL, but the reward is derived from the final output rather than the intermediate tool execution. The A2 paradigm is particularly effective for learning complex, multi-step reasoning strategies, such as when to search, what to search for, and how to integrate results, as it optimizes the agent's holistic reasoning policy.

The tool-centric paradigms, T1 and T2, shift the focus of adaptation from the agent to the external tools. The T1 paradigm, or "Agent-Agnostic Tool Adaptation," involves training or optimizing a tool independently of any specific agent. The goal is to improve the tool's standalone performance, such as retrieval accuracy or code generation quality, using offline data or environment feedback. This approach treats the tool as a plug-and-play component that can be used by any agent. The T2 paradigm, or "Agent-Supervised Tool Adaptation," represents a conceptual inversion. Instead of adapting the agent to use tools better, T2 adapts the tools to better serve a fixed, frozen agent. The adaptation signal is derived from the agent's own output, such as the quality of its final answer or the success of a task. This allows the tool to be optimized specifically for the needs of the given agent, leading to more efficient and effective performance. The T2 paradigm enables the creation of a symbiotic ecosystem where a powerful, frozen agent provides high-quality supervision signals, while lightweight, adaptive tools learn to translate, filter, and present information in the most useful form. This approach is particularly data-efficient, as the agent already possesses the necessary domain knowledge and reasoning ability, and the tool only needs to learn the procedural skill of effective interaction.

Experiment

- A1: Tool execution results as feedback enable supervised and reinforcement learning by using actual tool outcomes (e.g., correctness, improvement) as verifiable signals, allowing agent behavior refinement.

- T2: Tool adaptation via lightweight subagents (e.g., s3) achieves comparable performance to A2 methods (e.g., Search-R1) with significantly less data—2.4k samples vs. 170k—demonstrating a 70× reduction in data requirements and 33× faster training.

- On retrieval-augmented generation, s3 (T2) achieves 58.9% average accuracy and 76.6% on medical QA, outperforming Search-R1 (A2) at 71.8%, indicating better generalization and transferability.

- T2 methods exhibit superior modularity: new tools can be trained and swapped without retraining the core agent, avoiding catastrophic forgetting, while A2 requires full agent retraining for any change.

- T2’s approach simplifies learning by focusing on narrow procedural skills in subagents, leveraging a frozen backbone for reasoning and knowledge, leading to more efficient and scalable system evolution.

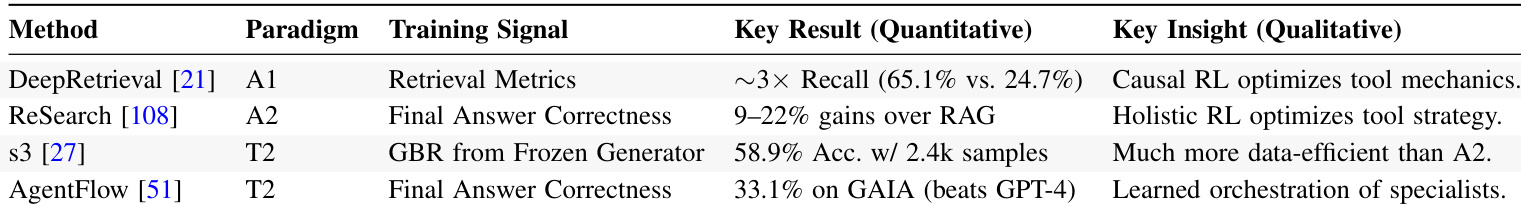

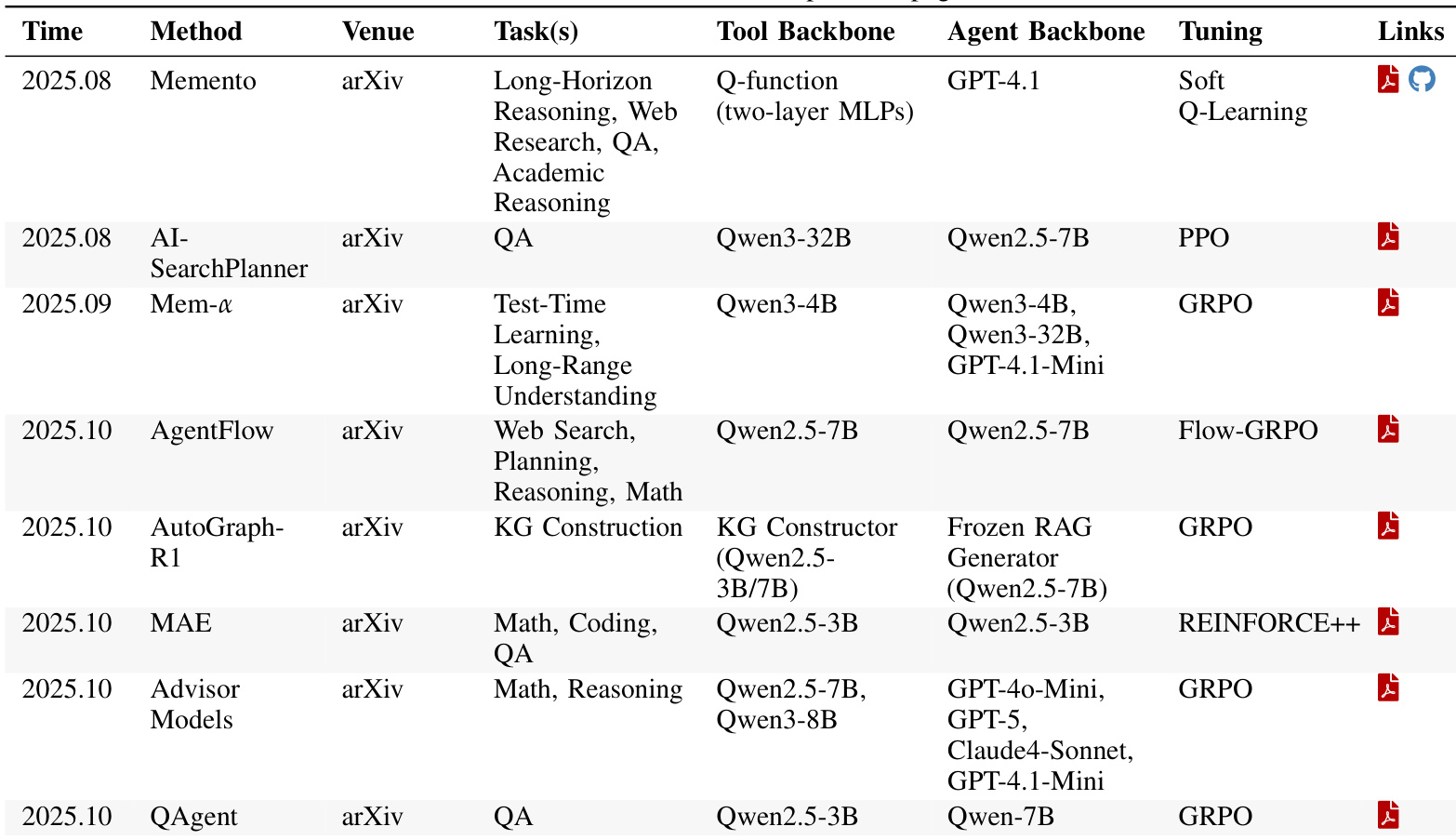

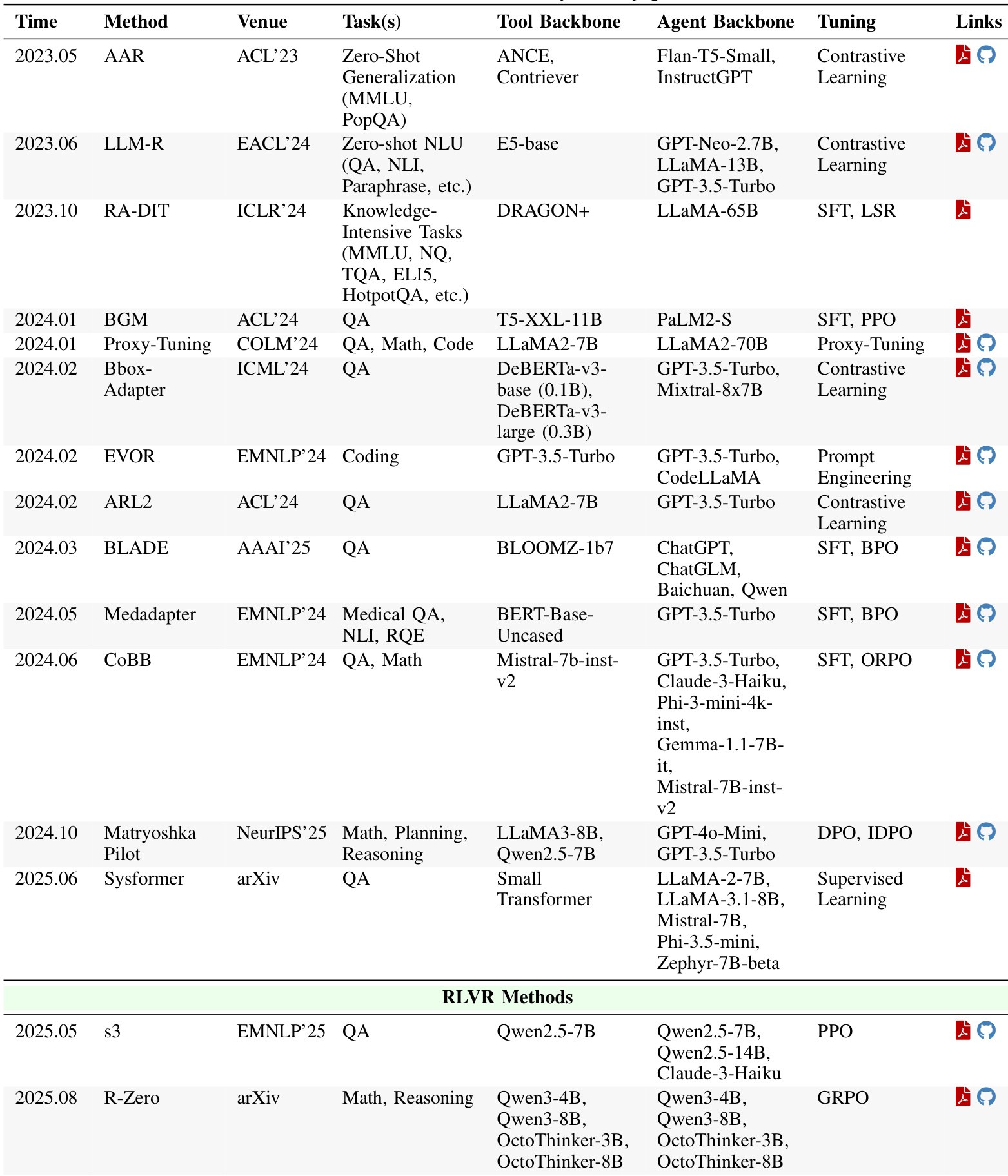

The authors use a table to compare different adaptation paradigms in agent systems, focusing on methods like DeepRetrieval, ReSearch, s3, and AgentFlow. Results show that T2 methods such as s3 achieve comparable performance to A2 methods like ReSearch with significantly less training data—only 2.4k samples versus 170k—and demonstrate better generalization, particularly in specialized domains.

The authors use a framework to compare four adaptation paradigms across cost, flexibility, data efficiency, and modularity, with Table 4 summarizing their qualitative differences. Results show that tool-centric approaches (T1 and T2) offer lower cost, higher system-level flexibility, and greater modularity compared to agent-centric methods (A1 and A2), which are more expensive and monolithic but provide high parametric flexibility.

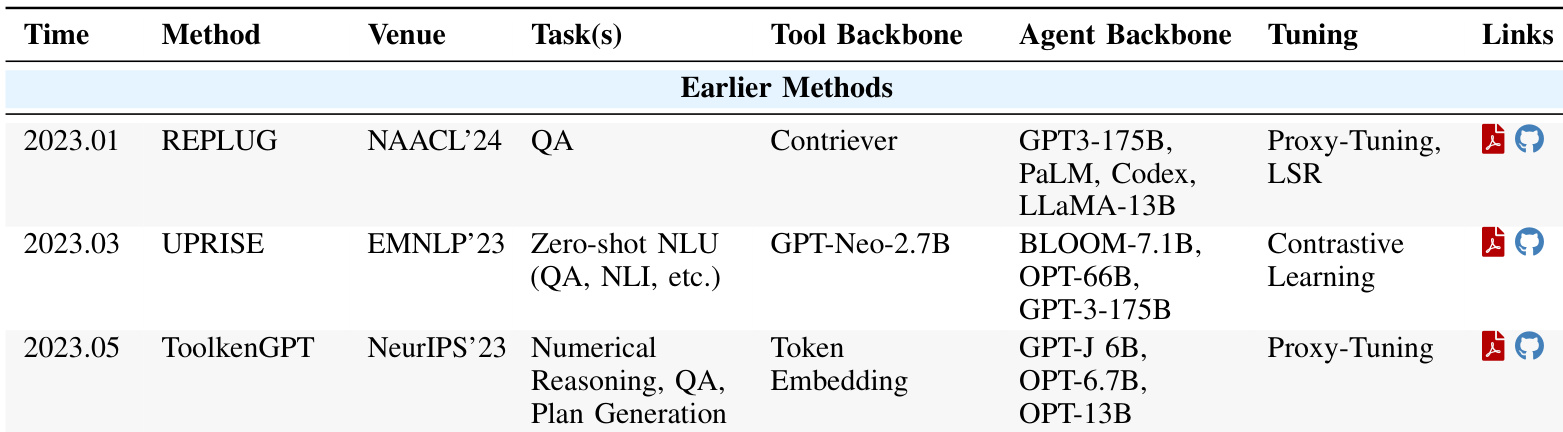

The authors use a table to compare various methods for tool-enhanced agent systems, focusing on their backbones, tasks, and training approaches. Results show that T2 methods like s3 achieve comparable performance to A2 methods such as Search-R1 with significantly less data and faster training, highlighting a substantial advantage in data efficiency and modularity.

The authors use a table to compare various methods for tool adaptation, focusing on their performance, backbones, and training approaches. Results show that T2 methods like s3 achieve comparable or better performance than A2 methods such as Search-R1 with significantly less data and faster training, highlighting a substantial improvement in data efficiency and modularity.

The authors use a table to compare earlier methods for tool execution signaling, highlighting their development timeline, tasks, tool and agent backbones, tuning techniques, and availability. Results show that these methods vary significantly in their backbone models, with some relying on large language models like GPT-3-175B and others using smaller models such as GPT-Neo-2.7B, and they employ different tuning strategies including proxy-tuning and contrastive learning.