Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

Latest Findings From Tsinghua University and the University of Chicago in Nature! AI Enables Scientists to Advance Their Careers by 1.37 Years and Reduces the Scope of Scientific Exploration by 4.631 TP3T.

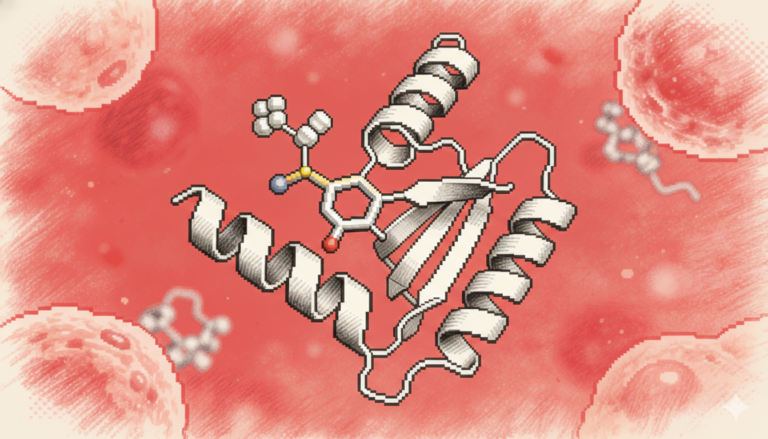

The rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) is profoundly rewriting the underlying logic of scientific research. From AlphaFold's accurate prediction of protein structure and winning the Nobel Prize, to ChatGPT driving autonomous laboratories to achieve high-throughput experiments, and large language models empowering scientific writing and results extraction, AI is demonstrating its enormous potential to improve scientific research productivity and amplify research visibility in diverse forms.

However, while AI tools are driving the progress of individual scientists, they are also prompting deep reflection on their impact on the overall development of science, with the core issue focusing on the potential conflict between individual and collective interests:Does AI merely assist scientists' individual academic development, or can it simultaneously drive diversified exploration and long-term progress in the scientific field?While existing research suggests that AI can bring significant benefits to individual scientists, it may also exacerbate inequality due to the AI education gap, and the evolution of citation patterns is quietly changing the research landscape. However, large-scale empirical measurements of AI's impact on science are still lacking, and its detailed and dynamic effects on the research ecosystem still need to be clarified.

Recently,A research team from Tsinghua University and the University of Chicago published their latest research findings in Nature, titled "Artificial intelligence tools expand scientists' impact but contract science's focus."By analyzing data from 41.3 million natural science papers and 5.37 million scientists between 1980 and 2025, a startling paradox regarding AI for Science has been revealed: AI is a "super accelerator" for individual research, but an "invisible shrinkage device" for collective science. This study not only boasts a massive dataset but also employs a sophisticated analytical framework.This provides unprecedented systematic evidence for the industry's understanding of the fundamental impact of AI on science.

Paper address:

Follow our official WeChat account and reply "AI Tools" in the background to get the full PDF.

More AI frontier papers:

https://hyper.ai/papers

Research approach: Constructing a complete causal chain from the individual to the collective.

The top-level design of this study is extremely clear. It does not stop at a simple description of the phenomenon, but constructs a complete analytical chain from identification to the exploration of the mechanism.

Starting point: Precise identification (What)

The first and most crucial step in the research was accurately distinguishing from a vast sea of literature which studies "use AI as a tool" rather than those "studying AI itself." The research team deliberately excluded works from the fields of computer science and mathematics.The focus is on six natural science disciplines, including biology, medicine, and chemistry.The research should focus on the "spillover effects" of AI on scientific production methods.

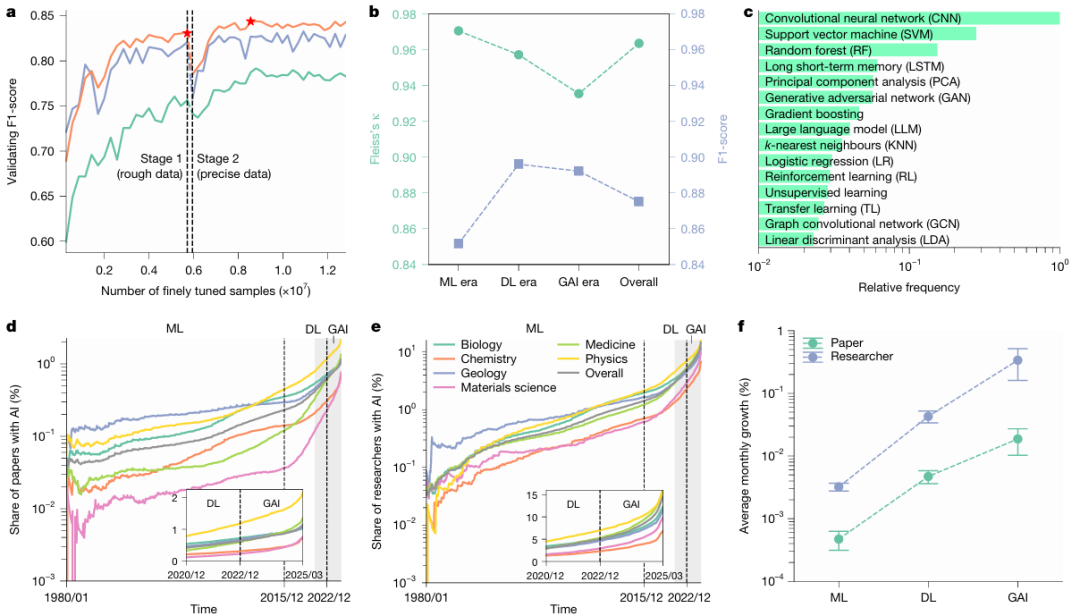

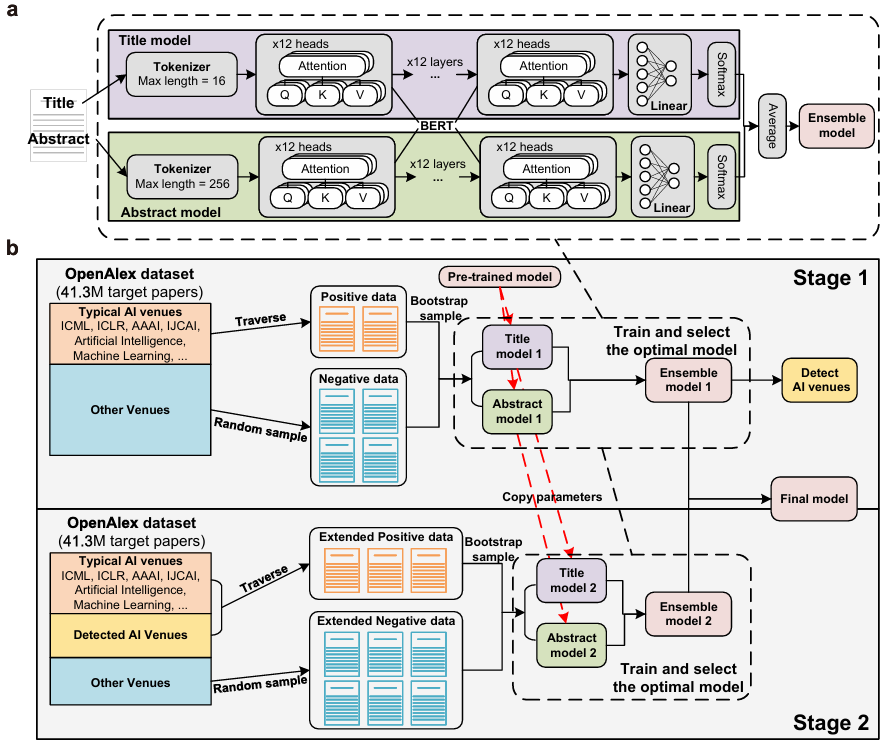

A: During the two-stage fine-tuning of the BERT pre-trained model, the AI's paper recognition performance continuously improved: the first stage used relatively coarse training data, and the second stage evolved a more accurate discrimination ability based on this data. Researchers independently trained two models based on paper titles (green) and abstracts (purple), respectively, and then integrated them into an ensemble model (orange). The model with the best performance in both stages was dynamically selected (red asterisk) to identify all relevant papers.

b: The accuracy of the recognition results was evaluated by human experts. For samples covering three stages of AI development, a high degree of consensus was reached among experts (κ ≥ 0.93). The model demonstrated high accuracy in validation against expert-annotated data, with an F1 score of at least 0.85.

c: Relative adoption frequency of the top 15 AI methods in each discipline during the selected AI development period.

d, e: Growth of AI-enhanced papers (d, n = 41,298,433) and researchers employing AI (e, n = 5,377,346) across the selected scientific disciplines from 1980 to 2025, in the three periods of machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and generative AI (GAI). The vertical axis is logarithmic.

f: The average monthly growth rate of the number of AI papers and researchers across all selected disciplines during each of the ML, DL, and GAI periods (n = 543 monthly observations). Error bars represent 99% confidence intervals (CI) centered on the mean.

Individual level: Quantifying individual impact

Based on precise identification, the study first answered the question, "What are the benefits for individual scientists?"By tracking researchers' annual publications, citations, and career transitions (from junior researcher to project leader), the research team arrived at a set of startling data:3.02 times more articles published, 4.84 times more citations, and 1.37 years longer career lead time.

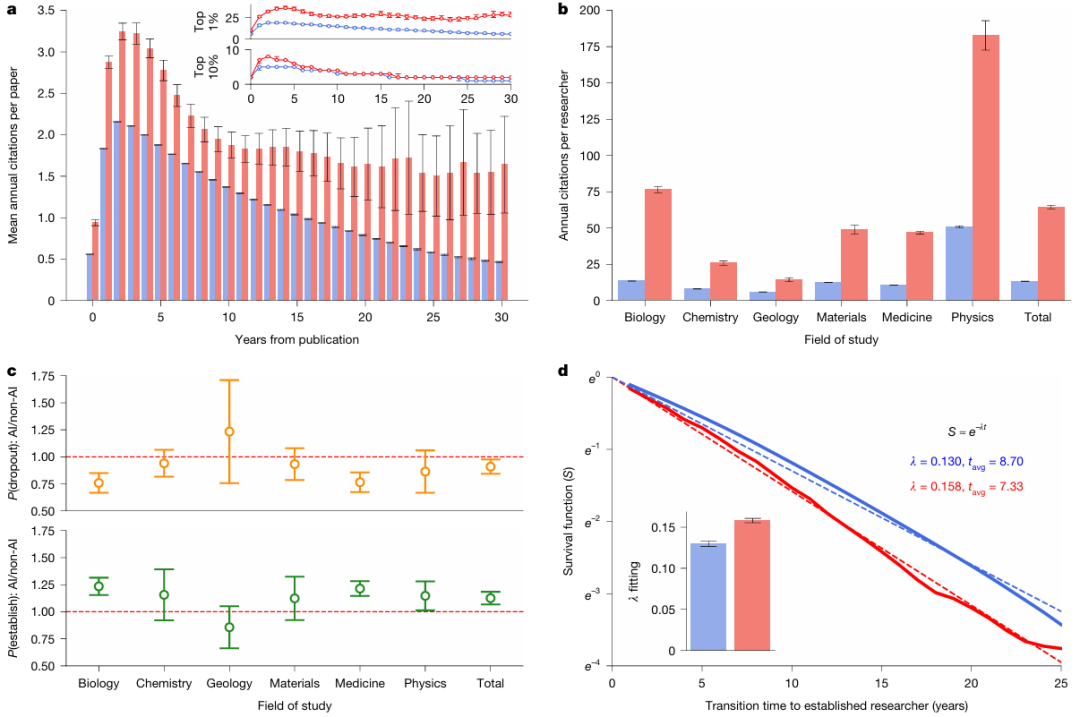

a: Average annual citations received after publication for AI papers (red) and non-AI papers (blue) (the inset shows the top 11 TP3T and top 101 TP3T quantiles, respectively; n = 27,405,011), indicating that AI papers generally attract more citations.

b: Comparison of average annual citations between researchers who used AI and those who did not (P < 0.001, n = 5,377,346), with researchers who used AI receiving an average of 4.84 times more citations than those who did not.

c: Among junior scientists, a comparison of the probabilities of role transitions between researchers who adopted AI and those who did not (all observations are for n = 46 years). Junior scientists who adopted AI were more likely to become experienced researchers and less likely to leave academia compared to their non-AI peers.

d: Survival function for transitioning from junior to senior researchers (P < 0.001, n = 2,282,029). This survival function fits well to an exponential distribution, indicating that junior scientists using AI complete this transition earlier. In all panels, error bars represent the 99% confidence interval (CI); the inset in a is centered at the 1% and 10% quantiles, while the remaining panels are centered at the mean. All statistical tests were performed using two-tailed t-tests.

Collective Level: Revealing Structural Change

Subsequently, the research perspective shifted from the micro-individual to the macro-ecosystem, raising a more profound question: "What changes occur in science as a whole when everyone benefits from AI?" To this end, the research team introduced two innovative collective indicators: the first is Knowledge Extent, which measures the breadth of coverage of research topics; the second is Follow-on Engagement, which measures the density of interaction between subsequent studies. The researchers treated subsequent results citing the same original study as a whole, calculating the mutual citation density among these results. The results showed that follow-on interactions in AI research decreased by approximately 221 TP3T.

Attribution: Exploring the Underlying Mechanisms (Why)

Finally, the research did not stop at the phenomena.Instead, it delves into the driving mechanism behind this "expansion-contraction" paradox.By eliminating factors such as popularity, early impact, and funding priorities, the research team pointed to the most fundamental reason—data availability. AI is naturally drawn to mature fields with abundant data and easy modeling, leading to a concentration of collective attention and a shrinking space for exploration.

This complete logical chain from "What" to "Why" makes the research conclusions highly convincing.

Research Highlights: Three Major Innovations, Directly Addressing the Core Issues

AI-powered paper recognition methods that go beyond keyword matching:

Traditional research often relies on keywords (such as "Neural Network") to screen AI papers, but this is highly susceptible to bias. This study employs a two-stage fine-tuning BERT model, trained separately on the paper title and abstract, and then integrates these results to make the final judgment.This method, after blind review by experts, achieved an F1 score as high as 0.875.This laid a solid and reliable data foundation for the entire study.

a: A schematic diagram of the deployed language model, which consists of a tokenizer, the core BERT model, and linear layers.

b: Schematic diagram of the two-stage model fine-tuning process, in which researchers designed specific methods for constructing positive and negative sample data at each stage.

A groundbreaking quantitative indicator for "knowledge breadth":

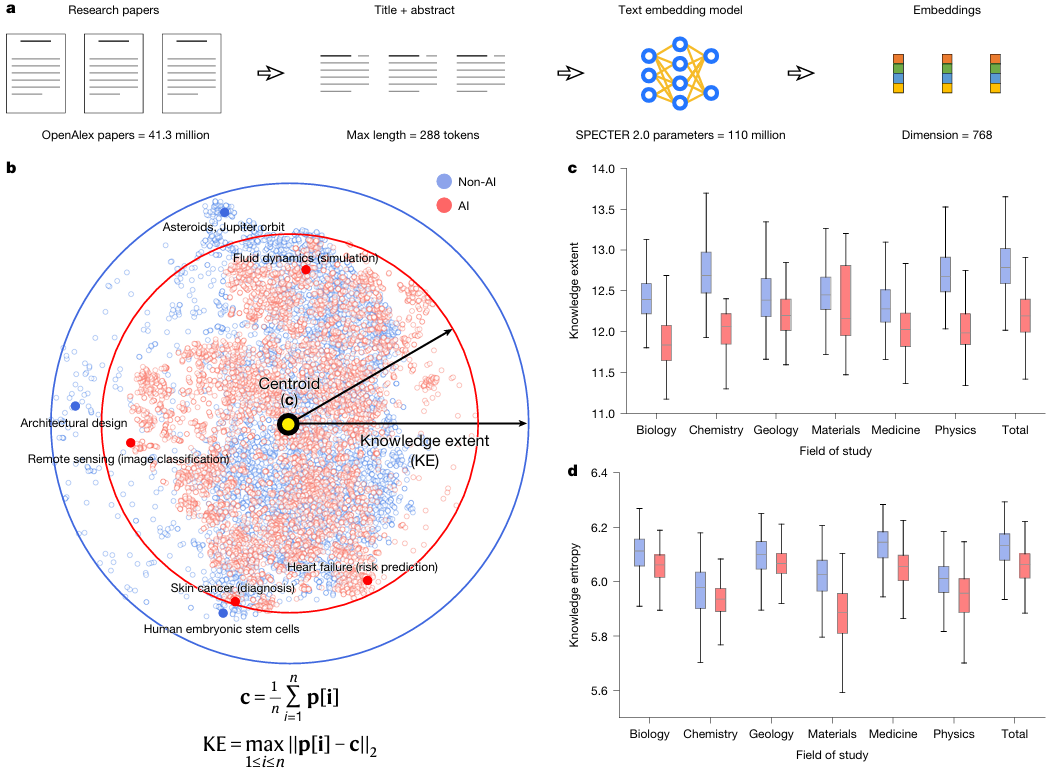

How do we measure the "scope of exploration" in a field? The research team used SPECTER 2.0, an embedding model specifically designed for scientific literature.Each paper is mapped to a 768-dimensional semantic vector space.The "knowledge breadth" of a collection of papers is defined as the maximum diameter it covers in that space. This approach, which transforms the abstract concept of "knowledge diversity" into a precisely calculable geometric distance, is a major innovation in scientometrics.

Revealing the academic interaction pattern of "lonely crowding":

Research has found that subsequent studies citing the same AI paper are less likely to cross-cite each other by 22%. This paints a picture of a "star-shaped" rather than a "networked" scientific research landscape: a large number of studies revolve around a few "star" AI achievements like planets, but lack lateral connections with each other. This state of "lonely crowds" is a dangerous sign that scientific creativity is being suppressed.

How can we use vector space to "measure" the breadth of science?

If the entire paper is a grand building, then its core technology is undoubtedly SPECTER 2.0 embedding model and knowledge extent.

Imagine the entire scientific knowledge system as a vast universe. SPECTER 2.0's role is to establish a precise coordinate system for this universe. By studying tens of millions of papers and their citation relationships, it transforms each paper into a 768-dimensional coordinate point (i.e., a vector). In this high-dimensional space, papers with similar topics have coordinate points close together; papers with vastly different topics have coordinate points far apart.

With this coordinate system, how do we measure the "territory" of a research field? The research team's approach is very ingenious:

sampling: A batch of papers is randomly selected from a specific field (such as AI-enhanced biological research).

position: Using SPECTER 2.0, all these papers were projected into a 768-dimensional knowledge universe, resulting in a set of coordinate points.

Find the center: Calculate the geometric center (centroid) of all these points.

Measure the diameter: The distance from the point furthest from the center is defined as the "breadth of knowledge" of this batch of papers.

a: Researchers used a pre-trained text embedding model to embed research papers into a 768-dimensional vector space and measure the breadth of knowledge in the papers within that space.

b: To facilitate visualization, researchers employed the t-distributed random neighborhood embedding (t-SNE) algorithm to compress the high-dimensional embeddings of 10,000 randomly selected papers (half of which were AI papers) into a two-dimensional space. As shown by the solid arrows and circular boundaries, the AI papers (whose knowledge breadth was calculated in the original space without dimensionality reduction) exhibit a smaller knowledge breadth across the entire natural sciences. Furthermore, the AI papers show a higher degree of clustering in the knowledge space, indicating a more focused attention on specific issues.

c: Comparison of knowledge breadth between AI and non-AI papers across disciplines (P < 0.001, n = 1,000 samples per discipline). The results show that AI research focuses on a more narrow knowledge space.

d: Comparison of knowledge entropy between AI and non-AI papers across disciplines (P < 0.001, n = 1,000 samples per discipline), with AI research exhibiting lower knowledge entropy. In panels c and d, box plots are centered at the median, with the upper and lower bounds of the boxes representing the first and third quartiles (Q1 and Q3), respectively, and the whiskers representing 1.5 times the interquartile range. All statistical tests were performed using the median test.

Using this method, the research team was able to fairly compare the size of the "territory" of AI research and non-AI research. The results clearly show that the median "knowledge breadth" of AI research is 4.631 TP3T smaller than that of non-AI research. This means that, driven by AI, scientists are unanimously flocking to a smaller, more concentrated area of knowledge.

Furthermore, the study analyzed citation distribution and found that AI research exhibits a stronger "Matthew effect":The top 22.21 TP3T AI papers received 801 TP3T of citations, and their citation inequality (Gini coefficient 0.754) was significantly higher than that of non-AI research (0.690).

Conclusion

In summary,This technical solution not only answers the question of "has science become narrower", but also tells researchers more precisely "how much narrower", "in which dimension it has become narrower", and "what kind of structure has been formed after narrowing".This is no longer a vague concern, but a reality that can be precisely depicted with data.

The value of this study lies not in negating AI, but in revealing, in the most rigorous way, the hidden costs researchers may incur when embracing AI. It reminds researchers that true scientific intelligence should not merely be a "tool" to improve efficiency, but rather a "partner" to expand the boundaries of human cognition.