Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

Die molekulare Struktur des Denkens: Kartierung der Topologie von Langen Ketten-des-Denkens-Reasoning

Die molekulare Struktur des Denkens: Kartierung der Topologie von Langen Ketten-des-Denkens-Reasoning

Zusammenfassung

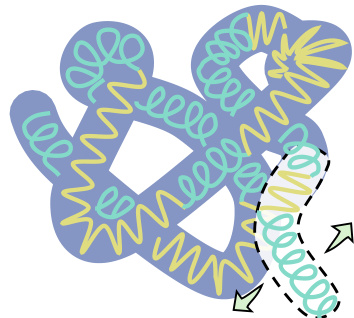

Große Sprachmodelle (LLMs) scheitern häufig daran, effektive lange Ketten des Denkens (Long CoT) durch Nachahmung menschlicher oder nicht-Long-CoT-LLMs zu erlernen. Um dieses Phänomen besser zu verstehen, schlagen wir vor, dass effektive und lernbare Long CoT-Pfade stabile, molekülähnliche Strukturen in einer einheitlichen Perspektive aufweisen, die durch drei Arten von Wechselwirkungen entstehen: Deep-Reasoning (kovalenzähnlich), Selbstreflexion (wasserstoffbindungsähnlich) und Selbstexploration (van-der-Waals-ähnlich). Die Analyse von verdichteten Pfaden zeigt, dass diese Strukturen durch Long CoT-Feinabstimmung entstehen und nicht durch Schlüsselwort-Nachahmung verursacht werden. Wir führen Effective Semantic Isomers ein und zeigen, dass nur Bindungen, die eine schnelle Konvergenz der Entropie fördern, stabiles Long CoT-Lernen unterstützen, während strukturelle Konkurrenz das Training beeinträchtigt. Aufbauend auf diesen Erkenntnissen präsentieren wir Mole-Syn, eine Verteilungsübertragungs-Graph-Methode, die die Synthese effektiver Long CoT-Strukturen leitet und die Leistung sowie die Stabilität im Reinforcement Learning über verschiedene Benchmarks hinweg verbessert.

One-sentence Summary

The authors from ByteDance Seed China, LARG at Harbin Institute of Technology, Peking University, and collaborating institutions propose MOLE-SYN, a distribution-transfer-graph method that synthesizes stable, molecule-like Long CoT reasoning structures through three interaction types—Deep-Reasoning, Self-Reflection, and Self-Exploration—enabling faster entropy convergence and improved reasoning performance and reinforcement learning stability across benchmarks.

Key Contributions

-

Long chain-of-thought (Long CoT) reasoning in LLMs fails to transfer effectively from human or weaker LLMs due to unstable, non-learnable reasoning structures, despite superficial similarity in output format, highlighting the need for deeper structural understanding beyond simple imitation.

-

The authors introduce a molecular analogy where stable Long CoT reasoning emerges from three interaction types—Deep-Reasoning (covalent-like), Self-Reflection (hydrogen-bond-like), and Self-Exploration (van der Waals-like)—and identify Effective Semantic Isomers whose bond distributions enable fast entropy convergence and robust learning, while incompatible structures cause instability.

-

MOLE-SYN, a distribution-transfer-graph method, synthesizes effective Long CoT structures by guiding bond formation based on these principles, demonstrating improved performance and reinforcement learning stability across benchmarks like GSM8K and AQuA-RAT, validated through distillation from strong teacher models.

Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have shown promise in multi-step reasoning through chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting, but they struggle to develop robust long-chain reasoning (Long CoT) from scratch, especially when relying on weak instruction-tuned models or human-generated rationales. Prior methods like supervised fine-tuning and distillation from low-quality or randomly sampled examples often fail to preserve coherence over extended reasoning trajectories or generalize to new tasks. The authors introduce a novel framework that models Long CoT as a molecular-like structure, where reasoning steps are conceptual nodes and their interactions are "bonds" with specific distributional properties. They demonstrate that distillation from high-quality reasoning models effectively transfers stable Long CoT structures, while superficial similarity in reasoning patterns—what they term semantic isomers—can lead to fragility or collapse in performance due to incompatible bond configurations. The key contribution is identifying that effective Long CoT learning depends not just on the presence of correct reasoning steps, but on the precise distribution and alignment of reasoning behaviors such as self-reflection and exploration, which must be preserved during training to achieve human-like coherence and adaptability.

Dataset

- The dataset is derived from the original SFT corpus, with two new subsets created to support self-exploration tasks.

- Both subsets maintain the same underlying trajectories and labels as the original, preserving the distributions of problem types, answer formats, and trajectory lengths.

- The subsets are constructed using specific keywords and phrases that encourage introspective reasoning, such as "maybe," "perhaps," "let's," "consider," "explore," "assume," and "if," to guide self-directed thinking.

- These keywords are used to filter and reframe prompts, promoting reflective and exploratory dialogue patterns.

- The authors use the dataset in a mixture ratio during training, combining it with other task-specific data to enhance the model’s ability to engage in self-exploration.

- No cropping is applied; instead, full trajectories are retained to preserve context and reasoning depth.

- Metadata is constructed around the presence and frequency of self-exploration keywords, enabling fine-grained analysis of introspective behavior in model outputs.

Method

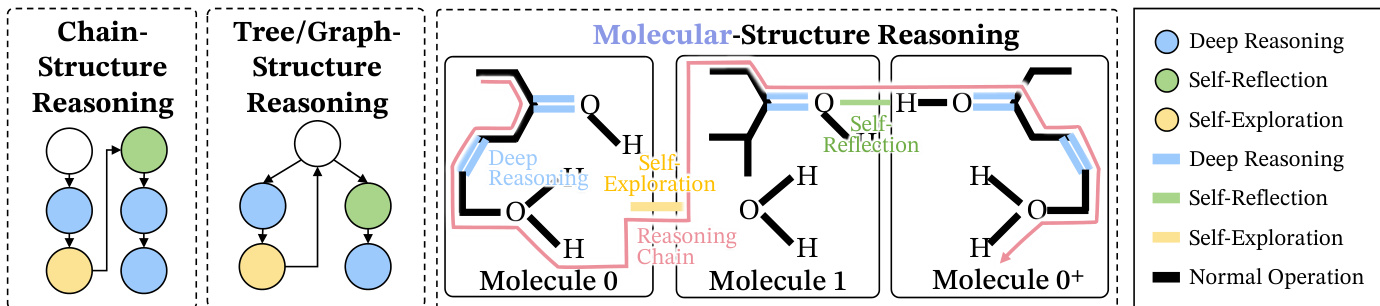

The authors propose a molecular-inspired framework for understanding and synthesizing effective long chain-of-thought (Long CoT) reasoning in large language models (LLMs). This framework models Long CoT as a macromolecular structure formed by three distinct interaction types, or "bonds," which collectively ensure reasoning stability. The core components are Deep Reasoning, Self-Reflection, and Self-Exploration. Deep Reasoning acts as covalent bonding, forming the primary logical backbone by establishing strong, direct dependencies between consecutive reasoning steps, such as extending a chain of deduction. Self-Reflection functions as hydrogen bonding, creating long-range corrective links that fold the reasoning chain back to prior steps to test consistency and prevent drift. Self-Exploration is analogous to van der Waals forces, enabling weak, transient associations that allow the model to probe new logical possibilities and branch into alternative paths without committing to a single conclusion. This molecular structure is contrasted with prior node-centric views, such as chain- or tree-like structures, which fail to capture the global, stabilizing interactions between these behaviors. The authors formalize this as a behavior-directed graph G=(V,E), where nodes represent reasoning steps and edges are labeled with one of three primary behaviors: Deep Reasoning (D), Self-Reflection (R), or Self-Exploration (E). The stability of the overall structure is determined by the distribution and arrangement of these bonds, with only specific configurations—termed "effective semantic isomers"—supporting stable learning.

The model's learning process is analyzed through the lens of attention energy, which is derived from the Transformer's attention mechanism. The authors define the attention energy Eij for a token pair as the negative of the pre-softmax logit, Eij=−sij=−dkqi⊤kj. This energy value is inversely related to the attention weight, meaning lower energy corresponds to a stronger, more probable connection. By analyzing the distribution of this energy across different bond types, the authors find a consistent ordering: Deep Reasoning bonds exhibit the lowest energy, followed by Self-Reflection, and then Self-Exploration, which has the highest energy. This ordering is supported by both empirical analysis and a theoretical proof under the assumption of Rotary Positional Embedding (RoPE), which shows that the expected energy of a bond is a function of the relative distance between the tokens it connects. This energy hierarchy is crucial because the attention mechanism, which follows a Boltzmann distribution, inherently favors lower-energy transitions. Consequently, paths that rely on Deep Reasoning and Self-Reflection bonds are exponentially more likely to be selected, effectively biasing the model towards stable, low-energy reasoning structures.

To synthesize these effective Long CoT structures, the authors introduce MOLE-SYN, a distribution-transfer-graph method. This framework operates by first estimating a behavior transition graph from a strong reasoning teacher model. The transition probabilities P(b′∣b) between different reasoning behaviors are computed from a corpus of high-quality Long CoT traces. This graph is then used to guide the synthesis of new reasoning trajectories. The synthesis process is a random walk on this transition graph, where the model is prompted to generate a step based on the current reasoning state, with the prompt explicitly defining the behavior (e.g., "You should conduct exploration behavior now."). This approach decouples the transfer of the structural behavior distribution from the surface form of the text, allowing for the generation of Long CoT data that match the target behavior patterns from scratch. The method is designed to be used with instruction-tuned LLMs, enabling the induction of complex reasoning structures without direct distillation from a powerful teacher.

The shaping function of each bond is further analyzed through geometric and dynamic metrics in semantic space. Deep Reasoning is shown to densify the core logical structure, reducing the volume of the smallest covering ball in the embedding space by 22% compared to a baseline, which signifies the formation of a tight, stable logical backbone. Self-Reflection acts as a stabilizer by "folding" the structure, consolidating the hydrophobic core and suppressing inconsistent branches, which reduces the system volume from 35.2 to 31.2. Self-Exploration, in contrast, expands the search space, increasing the volume from 23.95 to 29.22, which allows for broader exploration but at the cost of immediate stability. This process is analogous to protein folding, where Deep Reasoning forms the primary structure, Self-Exploration explores the conformational space, and Self-Reflection drives the system toward a stable, low-energy native state. The authors also quantify the dynamics of this process by analyzing the information flow and metacognitive oscillation, where the model alternates between high-entropy exploration and low-entropy validation states, with the prevalence of different reasoning bonds corresponding to these states.

The authors also investigate the learning process of supervised fine-tuning (SFT). They argue that SFT does not learn surface keywords but rather the underlying reasoning structure. This is demonstrated through a sparse auto-encoder analysis, which shows that Long CoT behavior is concentrated in a small set of discourse-control structures, with features activated by connective keywords like "Maybe" or "But" being dedicated to managing specific reasoning behaviors. A keyword manipulation experiment further supports this, showing that models trained on data with replaced or removed keywords achieve comparable reasoning performance to those trained on the original data, provided the underlying reasoning behaviors remain intact. This indicates that the model's capability is determined by the distribution of reasoning behaviors, not the specific lexical cues.

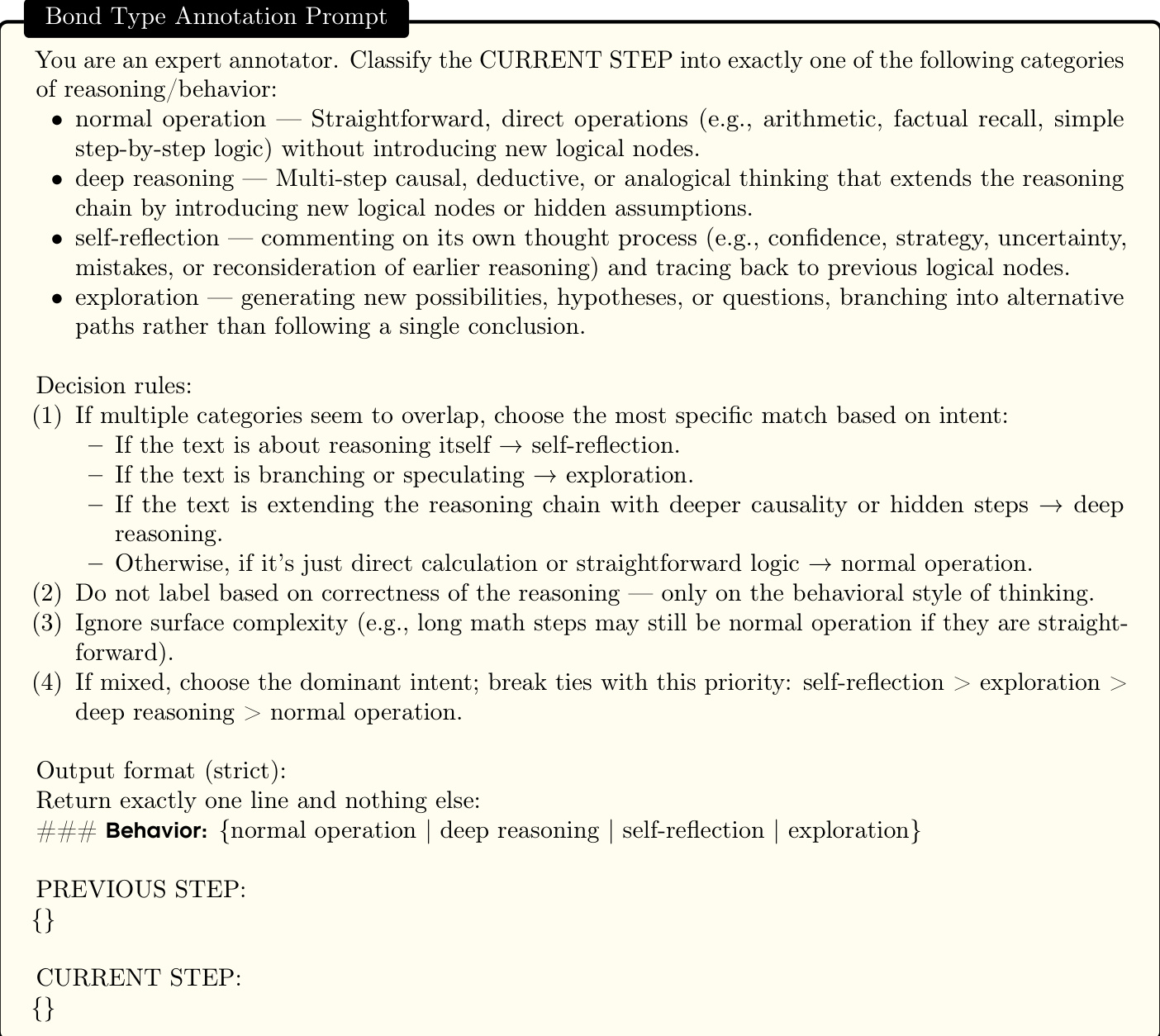

The process of labeling reasoning steps is formalized through a set of definitions and a prompt. A Long CoT trajectory is a sequence of steps τ=(u1,…,uT), where each step ut is a textual unit. The authors define three primary behaviors: Deep Reasoning (D) is a transition that extends the reasoning chain via non-trivial inference; Self-Reflection (R) is a transition that comments on or audits the model's own reasoning process; and Self-Exploration (E) is a transition that branches into alternative hypotheses. A final category, Normal Operation (N), covers routine progression. To automate this labeling, the authors provide a detailed prompt and decision rules for an expert annotator, which classifies the current step into one of these categories based on its behavioral style, not its correctness. The output format is strictly defined to ensure consistency.

The analysis of the Long CoT process is framed as a search for a stable, low-energy configuration. The authors hypothesize that the learning process seeks to minimize the overall attention energy. This is formalized by decomposing the trajectory-level average energy into a weighted sum of per-behavior averages, where the weights are the stationary frequencies of each behavior. Under mild ergodicity assumptions, the empirical frequency of each behavior converges to its stationary probability. The model's attention mechanism, which follows a Boltzmann distribution, exponentially favors lower-energy transitions. Therefore, if Deep and Self-Reflection behaviors have mean energies separated from Self-Exploration by a sufficient margin, the model will inherently bias its reasoning toward stable, low-energy structures. This provides a mechanistic explanation for why certain bond configurations are learnable and stable, while others are not.

Experiment

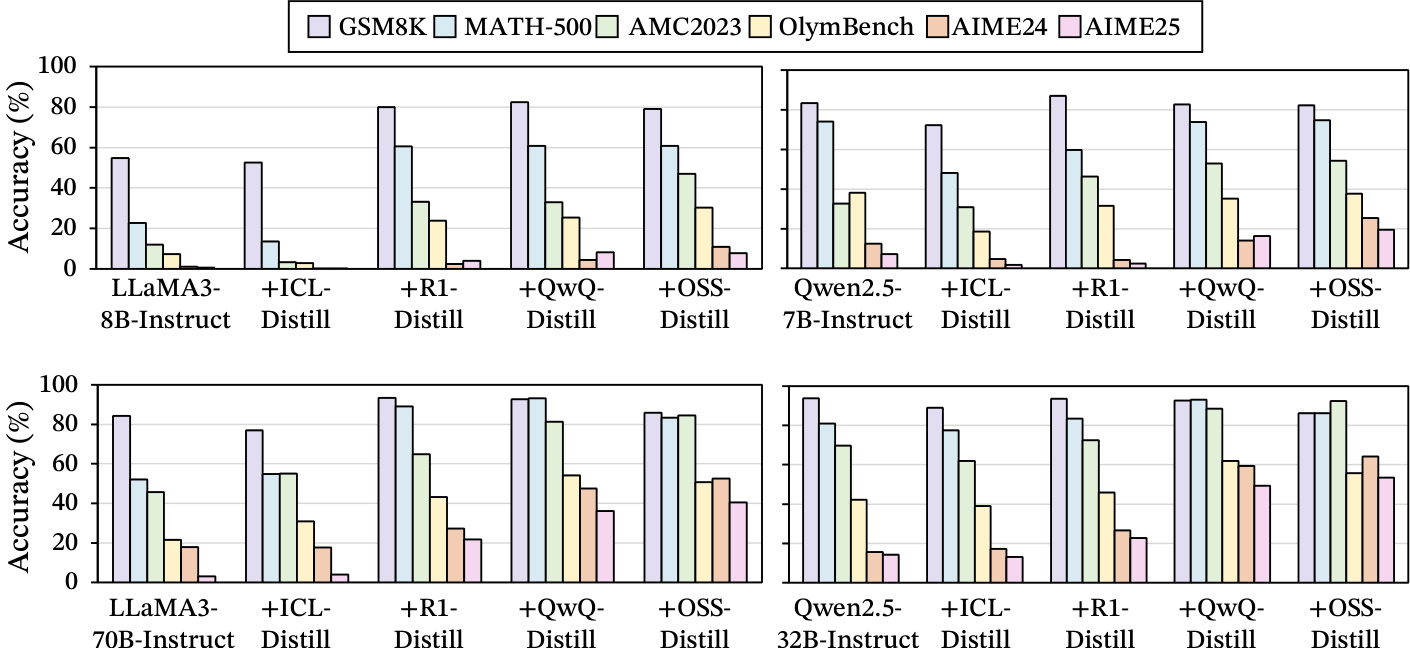

- Distillation from strong reasoning LLMs enables effective Long CoT learning, achieving significant performance gains on benchmarks such as GSM8K, MATH-500, and AIME2024, while distillation from weak instruction LLMs via ICL or fine-tuning on human-annotated traces fails to reproduce long-chain reasoning benefits.

- Stable, macromolecular-like reasoning bond distributions are observed across multiple models and tasks, with Pearson correlations exceeding 0.9 (p < 0.001) and stabilizing above 0.95 with sufficient sampling, indicating robust, transferable reasoning topologies.

- Long CoT exhibits a "logical folding" structure: deep reasoning acts as covalent bonding (72.56% of steps remain within close semantic distance), self-reflection mimics hydrogen bonding (81.72% of reflections reconnect to prior clusters), and exploration functions as van der Waals forces, linking distant semantic clusters with longer trajectory lengths.

- Well-structured semantic isomers derived from strong reasoning LLMs support consistent performance gains (correlation ~0.9), but small distributional changes cause large performance drops (>10%), highlighting fragility and the need for precise alignment in ICL distillation.

- Jointly training on two highly correlated yet structurally distinct reasoning frameworks (e.g., R1 and OSS) leads to structural chaos, with performance dropping significantly and self-correlation falling below 0.8, demonstrating that structural compatibility—not just statistical similarity—governs reasoning system coexistence.

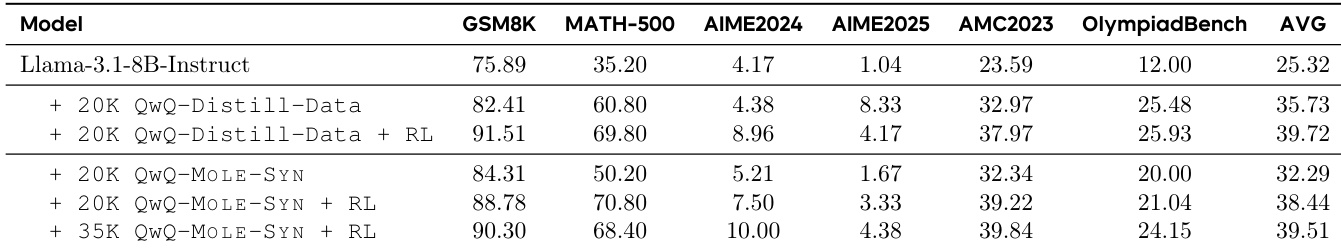

- MOLE-SYN successfully synthesizes Long CoT structures from instruction-level data without requiring full reasoning traces, achieving near-distillation performance and enabling superior and sustained reinforcement learning gains on MATH and AIME benchmarks.

- Summarization and token compression of Long CoT traces disrupt reasoning bond distributions and reduce distillation effectiveness, with accuracy drops observed beyond 45% compression, indicating that such methods can protect model structure from imitation.

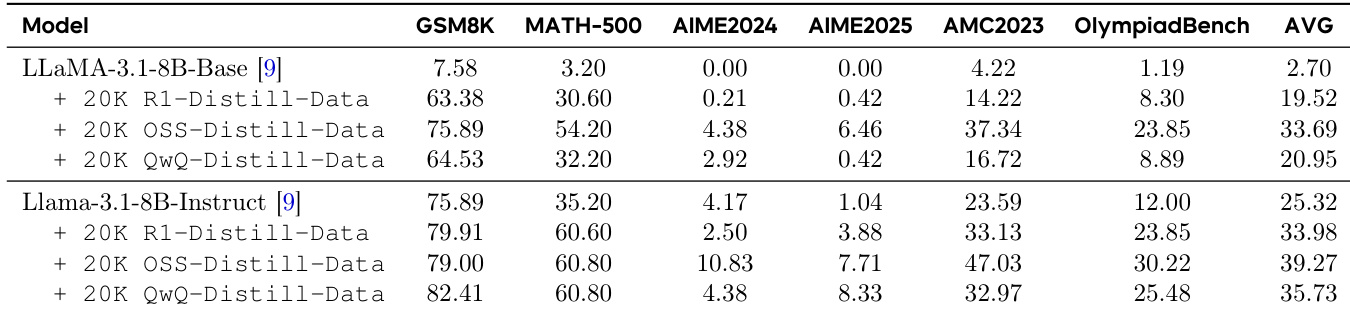

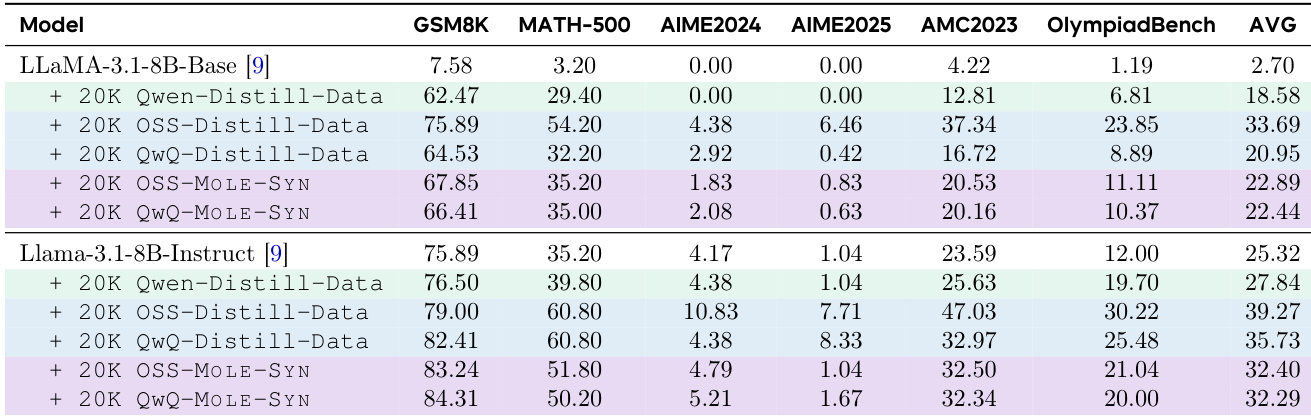

The authors use a table to compare the performance of different models and training data types across six benchmarks. Results show that distillation from strong reasoning LLMs, particularly using Qwen and OSS data, leads to significant performance gains over base models and instruction-tuned models. The MOLE-SYN method, which synthesizes Long CoT data, achieves performance comparable to distillation from strong reasoning models, indicating that effective reasoning structures can be generated without direct access to high-quality teacher data.

The authors use a series of experiments to compare the effectiveness of different data sources for training long chain-of-thought (Long CoT) reasoning in language models. Results show that distillation from strong reasoning LLMs consistently leads to the highest performance across all benchmarks, while distillation from weak instruction LLMs via in-context learning and fine-tuning on human-annotated traces yield significantly lower accuracy. This indicates that only high-quality, structured reasoning traces from advanced models can effectively teach Long CoT, with performance gains strongly tied to the fidelity of the underlying reasoning structure.

The authors use MOLE-SYN to synthesize Long CoT data from a weak instruction model, achieving performance comparable to distillation from strong reasoning models across six benchmarks. Adding reinforcement learning further improves results, with the best performance obtained when training on 35K synthesized samples followed by RL fine-tuning.

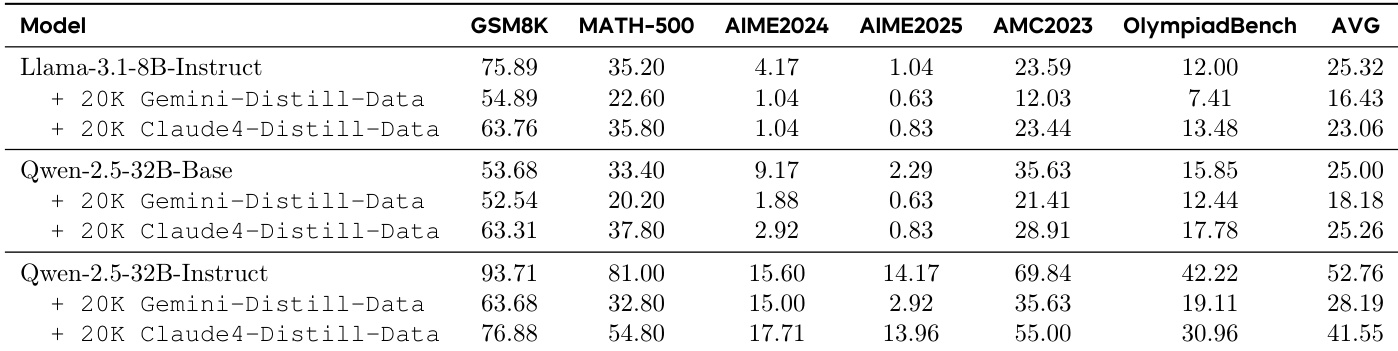

The authors use a table to compare the performance of different models and training data configurations across six benchmarks. Results show that distillation from strong reasoning LLMs, such as Gemini and Claude, significantly improves model performance compared to training on instruction-tuned LLMs or human-annotated traces. The best results are achieved when models are trained on distillation data from high-quality reasoning LLMs, with the Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct model achieving the highest average score of 52.76.

The authors use distillation from strong reasoning LLMs to train models on Long CoT data, showing significant performance improvements across multiple benchmarks compared to baseline models. Results show that distillation from high-quality reasoning traces, such as those from R1 and QwQ, leads to substantial gains, while distillation from instruction-tuned models or human-annotated traces yields much lower performance, indicating that only well-structured reasoning data effectively supports Long CoT learning.