Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

DiffVox: Ein differenzierbares Modell zur Erfassung und Analyse von professionellen Effektdistributionen

DiffVox: Ein differenzierbares Modell zur Erfassung und Analyse von professionellen Effektdistributionen

Chin-Yun Yu Marco A. Martínez-Ramírez Junghyun Koo Ben Hayes Wei-Hsiang Liao György Fazekas Yuki Mitsufuji

Zusammenfassung

Diese Studie stellt ein neuartiges und interpretierbares Modell, DiffVox, zur Anpassung von Gesangseffekten in der Musikproduktion vor. DiffVox, abgeleitet von „Differentiable Vocal Fx“, integriert parametrische Equalisierung, dynamische Dämpfung, Delay und Reverb mit effizienten, differenzierbaren Implementierungen, um eine gradientenbasierte Optimierung zur Schätzung der Parameter zu ermöglichen. Gesangsvoreinstellungen werden aus zwei Datensätzen abgerufen, bestehend aus 70 Tracks aus MedleyDB und 365 Tracks aus einer privaten Sammlung. Die Analyse der Parameterkorrelationen zeigt starke Beziehungen zwischen Effekten und Parametern, beispielsweise dass Hochpass- und Tiefen-Schelf-Filter oft gemeinsam wirken, um den tiefen Frequenzbereich zu formen, und dass die Delay-Zeit mit der Intensität der verzögerten Signale korreliert. Die Hauptkomponentenanalyse zeigt Verbindungen zu McAdams’ Timbre-Dimensionen, wobei die wichtigste Komponente die wahrgenommene Raumbreite moduliert, während die sekundären Komponenten die spektrale Helligkeit beeinflussen. Statistische Tests bestätigen die nicht-gaußsche Natur der Parameterverteilung und unterstreichen die Komplexität des Raums der Gesangseffekte. Diese ersten Erkenntnisse über die Parameterverteilung legen die Grundlage für zukünftige Forschung im Bereich der Modellierung von Gesangseffekten und automatischer Mischung. Unser Quellcode und die Datensätze sind unter https://github.com/SonyResearch/diffvox verfügbar.

One-sentence Summary

The authors, affiliated with Queen Mary University of London, Sony AI, and Sony Group Corporation, propose DiffVox, a differentiable vocal effects model integrating parametric EQ, dynamics, delay, and reverb for gradient-based parameter optimization; it reveals non-Gaussian parameter distributions and links effect configurations to McAdam’s timbre dimensions, enabling interpretable vocal processing and advancing automatic mixing in music production.

Key Contributions

- DiffVox introduces a differentiable, interpretable model for vocal effects matching in music production, integrating parametric equalisation, dynamic range control, delay, and reverb with efficient GPU-accelerated, differentiable implementations to enable gradient-based parameter estimation.

- The model is applied to 435 vocal tracks from MedleyDB and a private dataset, revealing strong parameter correlations—such as high-pass and low-shelf filter co-usage—and demonstrating that principal components of the parameter space align with McAdam’s timbre dimensions, particularly spaciousness and spectral brightness.

- Statistical analysis confirms the non-Gaussian nature of the effect parameter distribution, challenging common assumptions of uniform or Gaussian priors in audio processing, and the authors release the source code and dataset to support future research in audio effects modeling.

Introduction

The authors leverage differentiable signal processing to develop DiffVox, a model that enables gradient-based optimization for estimating vocal effects parameters in music production. This approach is critical for automating and refining vocal processing tasks, where precise control over equalization, compression, delay, and reverb is essential for achieving professional sound quality. Prior work has struggled with non-differentiable effects chains and limited interpretability, making automated parameter tuning difficult and often reliant on heuristic or trial-and-error methods. DiffVox overcomes these limitations by providing efficient differentiable implementations of key effects, allowing for end-to-end optimization. The model’s analysis of real-world vocal presets reveals meaningful parameter correlations and links to perceptual timbre dimensions, demonstrating that vocal effects operate in a structured, non-Gaussian space. These insights lay the groundwork for more intelligent, data-driven tools in automatic mixing and vocal production.

Dataset

-

The dataset comprises two sources: MedleyDB (76 tracks) and a private multi-track dataset called Internal (370 tracks), both sampled at 44.1 kHz. Internal focuses on modern mainstream Western music and includes paired dry and wet stems, while MedleyDB provides official metadata to identify vocal tracks.

-

For Internal, the authors recover the pairing between dry tracks and wet stems using cross-correlation analysis, as no explicit pairing information is available. Non-vocal stems are filtered out based on filename patterns. Only stems derived from a single raw track are retained to match the mono-in-stereo-out problem setting.

-

Stereo input tracks are processed by peak-normalizing both channels, computing their difference (side channel), and discarding any track where the maximum side energy exceeds -10 dB. The two channels are then averaged to form a mono source. Time alignment is applied to ensure optimal cross-correlation between dry and wet signals.

-

Each track is normalized to -18 dB LUFS using pyloudnorm. Segments of 12 seconds with 5-second overlap are extracted, with the final 7 seconds used for loss computation and the overlap serving as a warm-up. Silent segments are removed, and up to 35 segments are selected per training step to form a batch.

-

The model is trained for 2,000 steps per track using Adam with a learning rate of 0.01. The best checkpoint is selected based on minimum loss. Training occurs on a single RTX 3090 GPU, taking 20 to 40 minutes per track.

-

To handle non-linear effects like distortion or modulation not captured by the model, fitting runs are discarded if they show high minimum loss, unstable loss fluctuations, or no consistent decrease. This results in 6 excluded tracks from MedleyDB (~8%) and 5 from Internal (~1.3%).

-

Model parameters are initialized close to identity to ensure stable training. Key initializations include zero gains for PEQ peak filters, fixed cut-off frequencies for LP/HP filters, and specific starting values for dynamic range controls, delay, and FDN reverb. Impulse response lengths are set to 4 seconds for delay and 12 seconds for FDN reverb, with damping factor bounds limiting T60 to nine seconds to reduce aliasing.

-

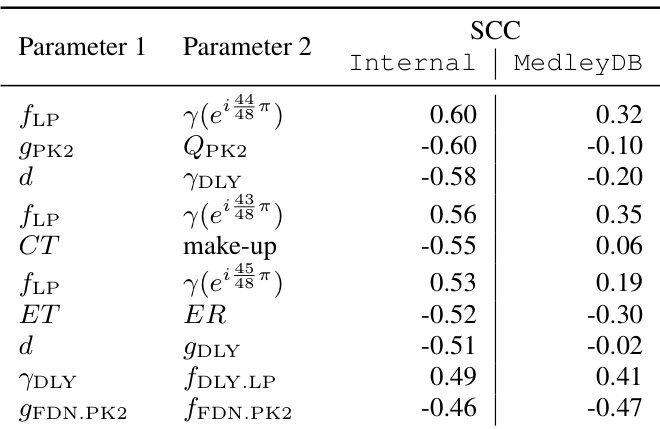

A Spearman correlation analysis is performed on 130 core parameters (excluding surrogate variables and lower triangular logits) to study inter-parameter relationships. High correlations are observed between delay time and feedback/gain, indicating trade-offs in perceived effect strength. Strong correlations also exist between PEQ filter gain and Q factor, and between compressor threshold and make-up gain.

-

Notably, high-frequency attenuation coefficients above 19.7 kHz correlate with LP filter cut-off frequency, suggesting reverb compensates for high-frequency loss by reducing decay rate. This points to potential improvements, such as increasing the LP cut-off bound or adding a wet/dry mix control.

-

Effect-wise correlation analysis reveals three main clusters via hierarchical clustering: spatial effects, HP and LS filters, and the remaining effects. The LS filter shows low autocorrelation and moderate correlation with the HP filter, indicating independent operation and collaborative low-end shaping.

Method

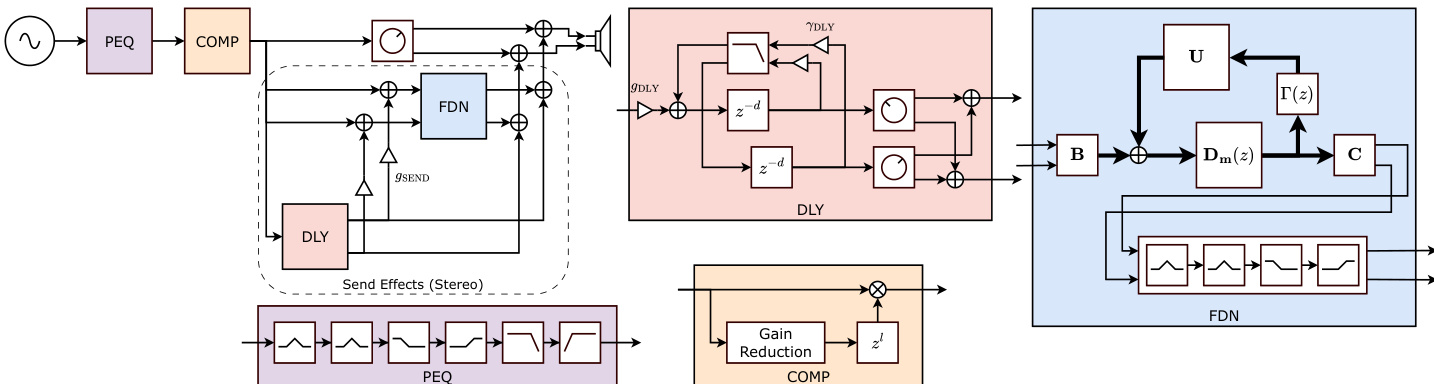

The authors leverage a differentiable audio effects model designed to reflect professional music production practices while enabling efficient training on GPUs. The overall framework, illustrated in the diagram, processes a mono input signal through a sequence of effects to produce a stereo output. The signal first passes through a parametric equaliser (PEQ), followed by a compressor and expander (COMP) acting as a dynamic range controller. The processed signal is then split into dry and wet paths. The dry signal is panned and mixed with the wet signal, which is processed by a ping-pong delay (DLY) and a feedback delay network (FDN) reverb. The final output is a stereo mix. The architecture is designed for a single-track, mono-in-stereo-out scenario, focusing on vocal processing to capture realistic effect configurations.

The parametric equaliser (PEQ) applies six filters: two peak, one low-shelf, one high-shelf, one low-pass, and one high-pass, implemented as Biquad filters. To accelerate computation, the authors employ a parallel prefix sum algorithm to express the recursive filter computation as an associative operation, enabling efficient backpropagation on GPUs. The compressor and expander (COMP) model uses parameters for thresholds, ratios, attack/release, and RMS smoothing, with a differentiable implementation that also benefits from parallel scan for its one-pole filters. A look-ahead feature is learned by approximating the continuous delay time using truncated sinc interpolation.

The ping-pong delay (DLY) is implemented with two delay lines that alternate between left and right channels, each with its own panner and a low-pass filter in the feedback path. The delay time is learned using a frequency-sampling approach, representing the effect as a convolution with a finite impulse response. The feedback delay network (FDN) reverb uses a stereo network of six delay lines with co-prime delay times. The FDN's transfer function is approximated using frequency-sampling, with a frequency-dependent attenuation filter parametrised by sampling its magnitude response at 49 points. A post-reverb PEQ is applied to the impulse response to correct for frequency-dependent decay and initial gain. The model also includes effect sends, where the delayed signal is sent to the reverb to colourise it, controlled by a send level parameter.

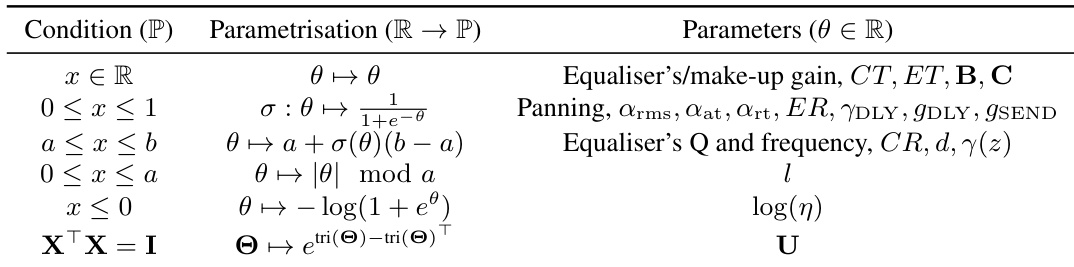

The model's total parameter count is 152, which is significantly reduced compared to more expressive models, prioritising a compact representation for analysis. The parameters are parametrised using specific functions to ensure they remain within their valid ranges. The training process optimises the effects parameters by minimising a composite loss function. This loss combines a multi-scale STFT (MSS) loss, which matches the magnitude spectrograms of the predicted and ground-truth signals across three scales, and a multi-scale Loudness Dynamic Range (MLDR) loss, which matches the microdynamics of the signals by comparing their loudness dynamics at different integration times. A regularisation term on the surrogate variable η is also included to encourage the damped sinusoidal approximation to converge to the unit circle. The final loss is a weighted sum of these components, applied to the left, right, mid, and side channels of the stereo output.

Experiment

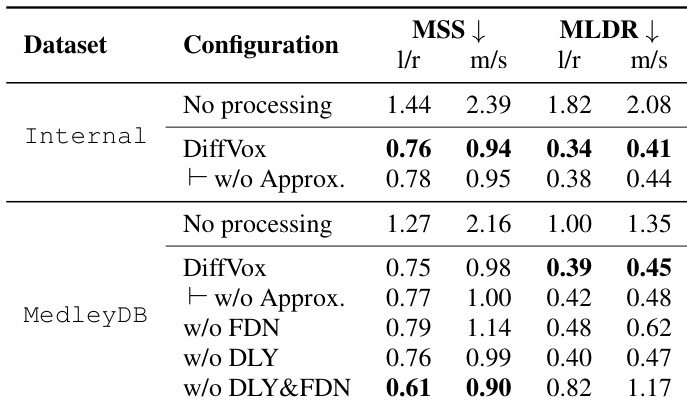

- DiffVox, the complete model incorporating spatial effects (PEQ, compressor, delay, FDN), achieves the best sound matching performance on MedleyDB, with the lowest MLDR loss and lower MSS than configurations with only delay or FDN, validating the importance of spatial effects for accurate microdynamic and spectral matching.

- Removing the approximation in the model leads to a slight performance drop due to mismatch from infinite IRs during inference, but DiffVox still outperforms configurations without FDN.

- PCA analysis on parameter logits reveals that Internal dataset parameters are more densely distributed than MedleyDB, with 65% of MedleyDB variance captured by the first ten PCs of the Internal model.

- The first two principal components correspond to meaningful audio transformations: the first enhances spaciousness and reverb decay, particularly in high frequencies, while the second creates a telephone-like band-pass effect, aligning with McAdam's timbre space.

- Multivariate normality tests show the parameter distribution is non-normal, indicating the need for more sophisticated generative models beyond Gaussian assumptions.

- The model successfully captures professional vocal effect parameters, with the released dataset and code supporting future research in automatic mixing and neural audio effects.

The authors use the table to compare the sound matching performance of different audio processing configurations on two datasets, Internal and MedleyDB. Results show that the DiffVox model achieves the best performance in matching microdynamics, as measured by MLDR loss, while also maintaining a lower spectral mismatch score (MSS) compared to configurations using only delay or FDN, indicating superior overall sound matching.

The authors use a differentiable model to analyze vocal effects processing, testing various configurations to evaluate sound matching performance. Results show that the complete model, DiffVox, achieves the best balance between spectral and dynamic fidelity, outperforming simpler setups in microdynamics loss while maintaining low spectral mismatch.

Results show that DiffVox achieves the best matching performance in MLDR and a lower MSS than configurations with only delay or FDN, indicating its effectiveness in capturing both spectral and dynamic aspects of audio. The performance drops slightly when removing the approximation, as the use of infinite IRs during inference introduces a mismatch compared to truncated FIRs.