Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

Vérifications de cohérence pour les autoencodeurs creux : les SAE surpassent-ils les bases aléatoires ?

Vérifications de cohérence pour les autoencodeurs creux : les SAE surpassent-ils les bases aléatoires ?

Anton Korznikov Andrey Galichin Alexey Dontsov Oleg Rogov Ivan Oseledets Elena Tutubalina

Résumé

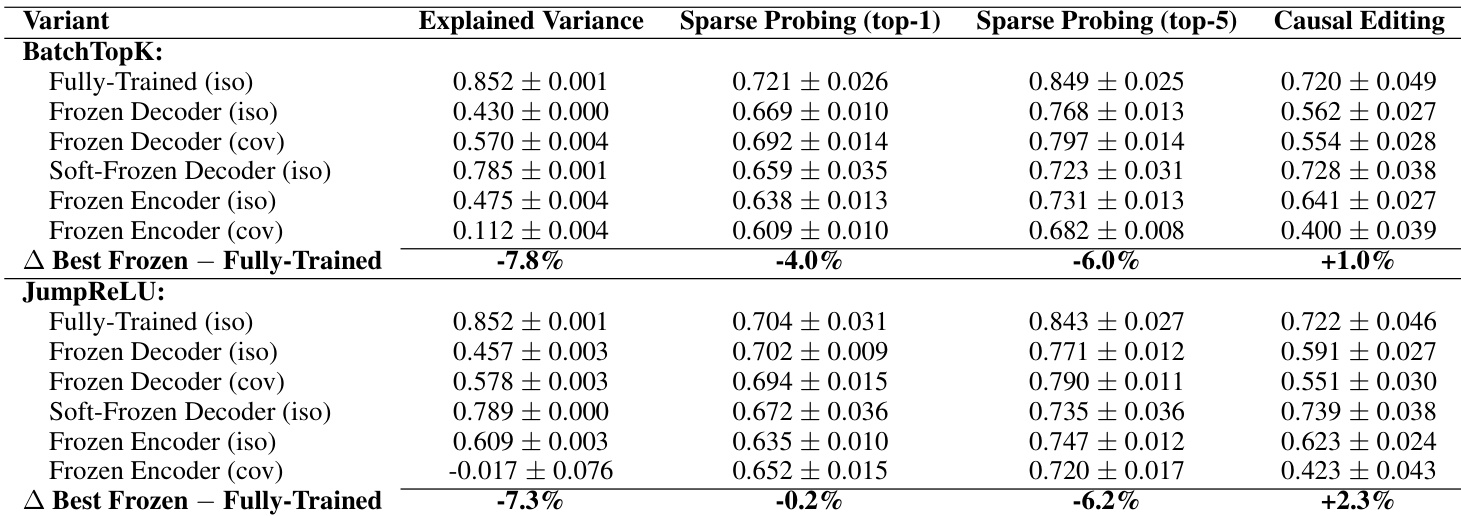

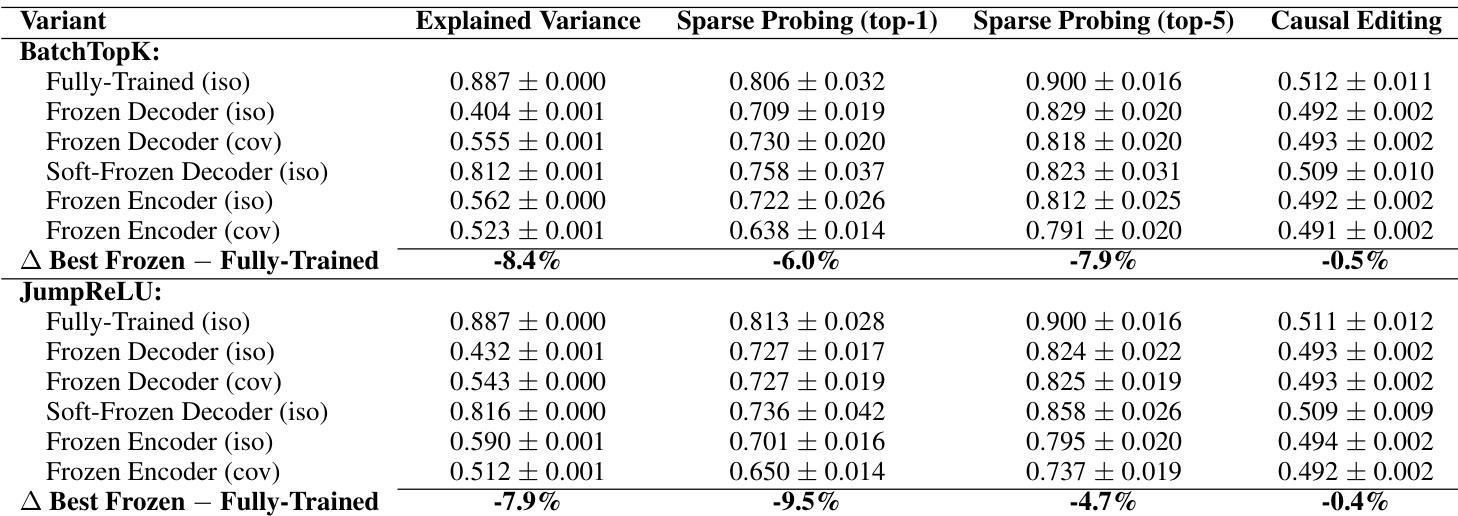

Les autoencodeurs creux (Sparse Autoencoders, SAE) se sont imposés comme un outil prometteur pour interpréter les réseaux de neurones en décomposant leurs activations en ensembles creux de caractéristiques interprétables par l’humain. Des travaux récents ont introduit plusieurs variantes de SAE et les ont efficacement mise à l’échelle sur des modèles de pointe. Malgré l’enthousiasme croissant, un nombre croissant de résultats négatifs dans des tâches ultérieures met en doute la capacité des SAE à récupérer des caractéristiques significatives. Pour étudier directement cette question, nous menons deux évaluations complémentaires. Sur un cadre synthétique où les caractéristiques véritables sont connues, nous montrons que les SAE ne récupèrent que 9 % des caractéristiques réelles, malgré un taux de variance expliquée de 71 %, ce qui indique qu’ils échouent à leur tâche fondamentale même lorsque la reconstruction est performante. Pour évaluer les SAE sur des activations réelles, nous introduisons trois biais (baselines) qui contraindent les directions des caractéristiques SAE ou leurs motifs d’activation à des valeurs aléatoires. À travers des expériences étendues sur plusieurs architectures SAE, nous montrons que nos biais atteignent des performances comparables aux SAE entièrement entraînés en termes d’interprétabilité (0,87 contre 0,90), de sondage creux (0,69 contre 0,72) et d’édition causale (0,73 contre 0,72). Ensemble, ces résultats suggèrent que, dans leur état actuel, les SAE ne décomposent pas de manière fiable les mécanismes internes des modèles.

One-sentence Summary

The authors from Skoltech and HSE demonstrate that Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) recover only 9% of true features despite high reconstruction, and show random-baseline variants match trained SAEs in interpretability tasks, challenging SAEs’ reliability for decomposing neural network mechanisms.

Key Contributions

- SAEs fail to recover true features in synthetic settings despite high reconstruction performance, revealing that explained variance does not imply meaningful decomposition—only 9% of ground-truth features were recovered even with 71% variance explained.

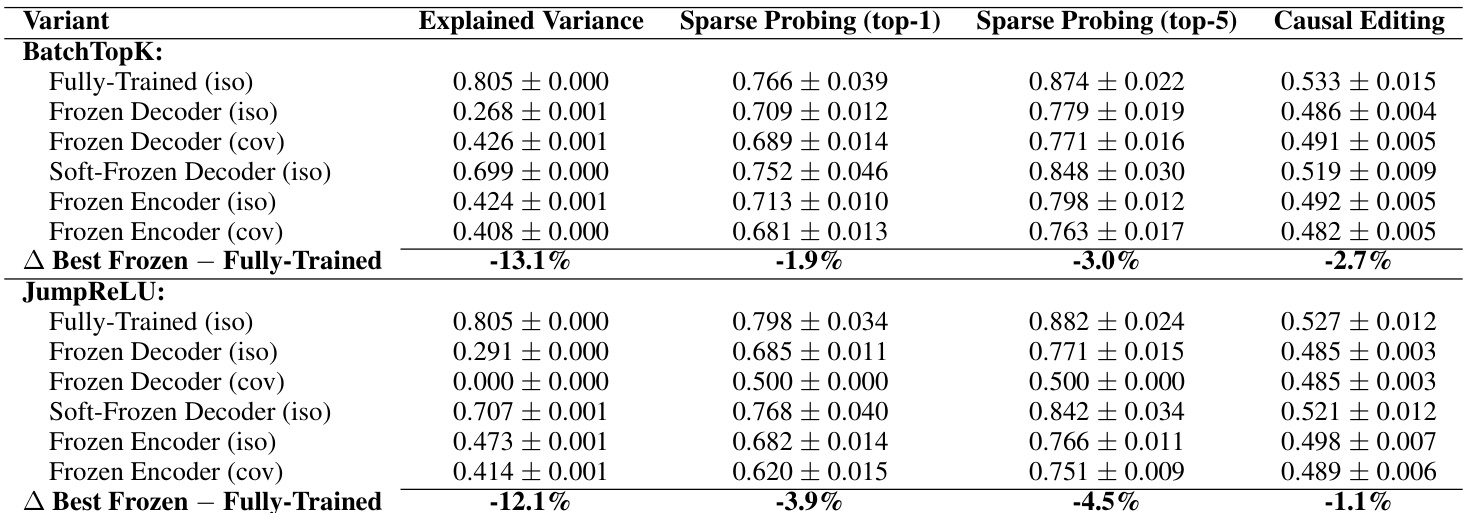

- We introduce three simple baselines that fix encoder or decoder parameters to random values, enabling direct evaluation of whether learned feature directions or activations contribute meaningfully to SAE performance on real model activations.

- Across multiple SAE architectures and downstream tasks—including interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing—these baselines match fully trained SAEs, suggesting current SAEs do not reliably learn interpretable internal mechanisms.

Introduction

The authors leverage sparse autoencoders (SAEs) to interpret large language models, aiming to decompose dense activations into human-interpretable features — a goal critical for understanding model behavior, safety, and alignment. However, prior work lacks ground truth to verify whether SAEs recover meaningful structure, and recent studies show SAEs often underperform on downstream tasks despite strong reconstruction scores. The authors introduce three simple baselines — Frozen Decoder, Frozen Encoder, and Soft-Frozen Decoder — that fix or constrain learned parameters to random values, finding these match fully trained SAEs across interpretability, probing, and causal editing tasks. Their synthetic experiments further reveal SAEs recover only high-frequency features, not the intended decomposition, suggesting current evaluation metrics may be misleading and that SAEs may not learn genuinely meaningful features.

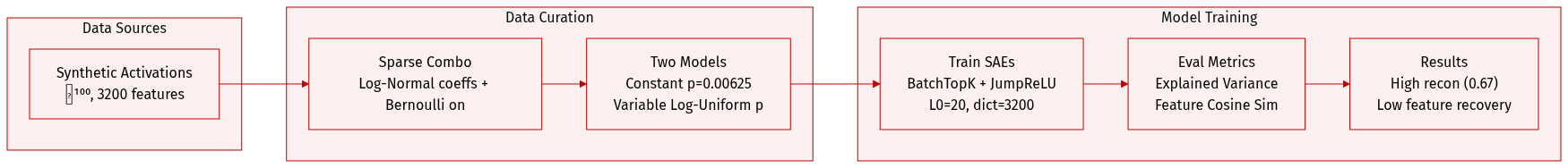

Dataset

- The authors generate synthetic activations in ℝ¹⁰⁰ using an overcomplete dictionary of 3200 ground-truth feature vectors sampled uniformly from the unit sphere.

- Each activation vector is a sparse linear combination of these features, with coefficients drawn from a Log-Normal(0, 0.25) distribution and binary activation indicators from Bernoulli(p_i).

- Two activation probability settings are tested: a Constant Probability Model (p_i = 0.00625) and a Variable Probability Model (p_i ~ Log-Uniform(10⁻⁵.⁵, 10⁻¹.²)), both yielding an average of 20 active features per sample.

- The synthetic dataset is used to train two SAE variants—BatchTopK and JumpReLU—with dictionary size 3200 and target L0 sparsity of 20, matching the ground truth.

- Reconstruction fidelity is measured via explained variance, comparing the SAE’s output to the original activation, normalized by the variance of the mean prediction.

- Feature recovery is evaluated by computing the maximum cosine similarity between each ground-truth feature and its closest SAE decoder vector.

- Despite high explained variance (0.67), neither SAE variant recovers meaningful ground-truth features in the constant probability setting, highlighting alignment challenges.

Method

The authors leverage Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) to decompose neural network activations into interpretable, sparse feature representations. This approach directly addresses polysemanticity — the phenomenon where single neurons encode multiple unrelated concepts — by operating under the superposition hypothesis. This hypothesis posits that neural networks compress more features than their dimensional capacity by encoding them as sparse linear combinations of directions in activation space. For an input activation vector x∈Rn, the model assumes:

x=j=1∑maj⋅fj,where fj are the true underlying feature directions (with m≫n) and aj are sparse, nonnegative coefficients. The SAE approximates this decomposition by learning a dictionary of feature vectors dj and sparse activations zj such that:

x≈x^=j=1∑mzj⋅dj=Wdecz,where Wdec is the decoder matrix whose columns are the learned feature directions. The encoder maps the input via z=f(Wencx+benc), where f is typically a sparsity-inducing activation like ReLU, and benc is a learned bias. The full reconstruction includes a decoder bias: x^=Wdecz+bdec. To enable richer representations, SAEs are typically overcomplete, with an expansion factor k=m/n>1, commonly set to 16, 32, or 64.

Training is guided by a composite objective that balances reconstruction fidelity and sparsity:

L=Ex[∥x−x^∥22+λ∥z∥1],where λ tunes the trade-off. Alternative sparsity mechanisms include L0 constraints or adaptive thresholds, but the core principle remains: optimizing for both reconstruction and sparsity should yield feature directions dj that align with true model features fj and correspond to human-interpretable concepts.

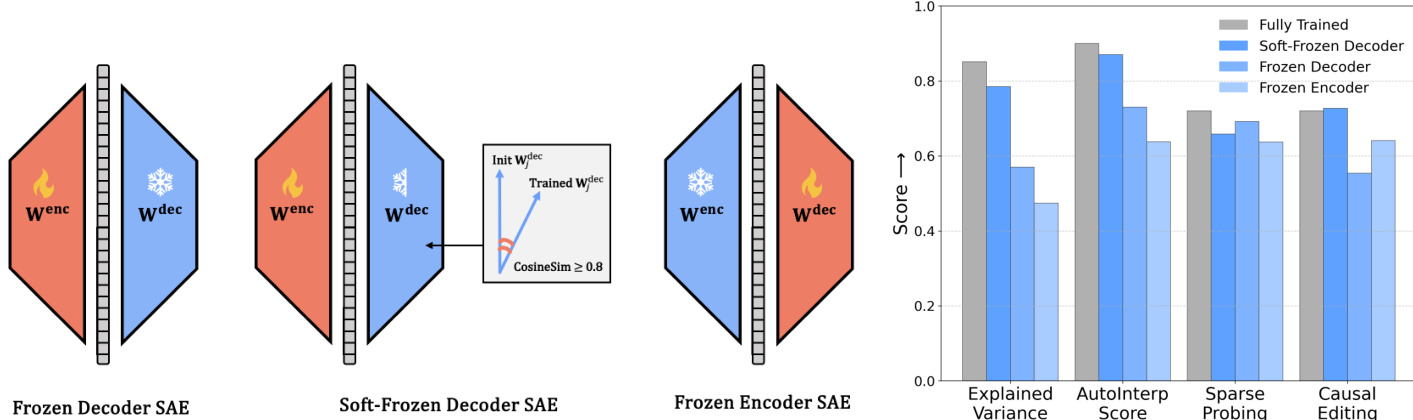

As shown in the figure below, the authors explore three training regimes: Frozen Decoder, Soft-Frozen Decoder, and Frozen Encoder SAEs. In the Frozen Decoder variant, the decoder weights are fixed after initialization, while the encoder is trained. In Soft-Frozen Decoder, the decoder is initialized with pre-trained weights and updated only if the cosine similarity with the initial weights remains above 0.8. In Frozen Encoder, the encoder is fixed and only the decoder is trained. These configurations are evaluated across metrics including Explained Variance, AutoInterp Score, Sparse Probing, and Causal Editing, revealing trade-offs in interpretability and reconstruction performance.

Experiment

- Synthetic experiments show SAEs recover only 9% of true features despite 71% explained variance, indicating reconstruction success does not imply feature discovery.

- On real LLM activations, SAEs with frozen random components match fully trained SAEs in interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing, suggesting performance stems from random alignment rather than learned decomposition.

- Feature recovery is biased toward high-frequency components, leaving the long tail of rare features largely uncovered.

- Soft-Frozen Decoder baselines perform nearly as well as trained SAEs, supporting a “lazy training” regime where minimal adjustments to random initializations suffice for strong metrics.

- TopK SAE succeeds in synthetic settings but fails to translate to real data, where frozen variants still perform comparably, undermining claims of meaningful feature learning.

- Results across vision models (CLIP) echo findings in language models, showing random SAEs produce similarly interpretable features without training.

- Overall, current SAEs do not reliably decompose internal model mechanisms; standard metrics may reflect statistical artifacts rather than genuine feature discovery.

The authors use frozen random baselines to test whether Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) genuinely learn meaningful features or merely exploit statistical patterns. Results show that SAEs with randomly initialized and frozen components perform nearly as well as fully trained ones across reconstruction, interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing metrics, suggesting current SAEs do not reliably decompose model internals into true features.

The authors use frozen random baselines to test whether Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) genuinely learn meaningful features or merely exploit statistical patterns. Results show that SAEs with key components fixed to random values perform nearly as well as fully trained models across reconstruction, interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing tasks, suggesting current SAEs do not reliably decompose internal model mechanisms.

The authors use frozen random baselines to test whether Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) genuinely learn meaningful features or merely exploit statistical patterns. Results show that SAEs with key components fixed at random initialization perform nearly as well as fully trained models across reconstruction, interpretability, sparse probing, and causal editing tasks, suggesting current SAEs do not reliably decompose internal model mechanisms.