Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

CAR-bench : Évaluation de la cohérence et de la prise en compte des limites des agents LLM face à l'incertitude du monde réel

CAR-bench : Évaluation de la cohérence et de la prise en compte des limites des agents LLM face à l'incertitude du monde réel

Johannes Kirmayr Lukas Stappen Elisabeth André

Résumé

Les benchmarks existants pour les agents basés sur les grands modèles linguistiques (LLM) se concentrent sur la réussite des tâches dans des conditions idéalisées, tout en négligeant la fiabilité dans les applications réelles destinées aux utilisateurs. Dans des domaines tels que les assistants vocaux embarqués, les utilisateurs émettent souvent des requêtes incomplètes ou ambigües, générant une incertitude intrinsèque que les agents doivent gérer à travers la dialogue, l’utilisation d’outils et le respect des politiques. Nous introduisons CAR-bench, un benchmark destiné à évaluer la cohérence, la gestion de l’incertitude et la prise de conscience des capacités chez les agents LLM multi-tours utilisant des outils, dans le cadre d’un assistant automobile. L’environnement comprend un utilisateur simulé par un LLM, des politiques spécifiques au domaine, ainsi que 58 outils interconnectés couvrant la navigation, la productivité, la recharge et le contrôle du véhicule. Au-delà de la simple réussite des tâches, CAR-bench introduit des tâches de « hallucination » qui testent la prise de conscience des limites des agents lorsque des outils ou des informations manquent, et des tâches de « déambiguïsation » qui exigent de résoudre l’incertitude par des clarifications ou une collecte d’informations internes. Les résultats obtenus avec les modèles de base révèlent des écarts importants entre une réussite occasionnelle et une réussite cohérente sur toutes les catégories de tâches. Même les LLM de pointe en raisonnement obtiennent un taux de réussite cohérente inférieur à 50 % pour les tâches de déambiguïsation, en raison d’actions prématurées, et violent fréquemment les politiques ou inventent des informations pour satisfaire les requêtes dans les tâches d’hallucination, soulignant ainsi la nécessité de développer des agents LLM plus fiables et plus conscients d’eux-mêmes dans des environnements réels.

One-sentence Summary

Johannes Kirmayr, Lukas Stappen, and Elisabeth André from BMW Group Research and Augsburg University introduce CAR-bench, a novel benchmark evaluating LLM agents’ reliability in in-car assistants through uncertainty handling, policy adherence, and tool use, exposing critical gaps in current models’ consistency and self-awareness under real-world constraints.

Key Contributions

- CAR-bench introduces a new evaluation framework for LLM agents in automotive assistant settings, featuring 58 interconnected tools and 19 domain policies to assess reliability under real-world constraints like ambiguity, partial information, and safety rules.

- It defines two novel task types—Hallucination tasks to measure limit-awareness when tools or data are missing, and Disambiguation tasks to evaluate how agents resolve uncertainty through clarification or internal reasoning—addressing critical gaps in existing benchmarks.

- Baseline evaluations show even top reasoning LLMs struggle, achieving under 50% consistent success on Disambiguation tasks and frequently violating policies or hallucinating in Hallucination tasks, highlighting the need for more self-aware and consistent agent behavior in deployment scenarios.

Introduction

The authors leverage the automotive in-car assistant domain to evaluate how well LLM agents handle real-world uncertainty, where users issue ambiguous or incomplete requests and agents must navigate tool limitations and strict safety policies. Prior benchmarks often assume idealized conditions—complete information, full tool coverage, and single-turn interactions—failing to capture the need for consistent, policy-compliant behavior under ambiguity or missing capabilities. CAR-bench introduces two novel task types: Hallucination tasks, which test whether agents admit when tools or data are unavailable instead of fabricating responses, and Disambiguation tasks, which measure the agent’s ability to resolve uncertainty through clarification or internal checks before acting. Their framework includes 58 interconnected tools, 19 domain policies, and an LLM-simulated user to enable multi-turn, dynamic evaluation, revealing that even top reasoning models struggle with consistent performance—especially on Disambiguation tasks—and often violate policies or hallucinate to satisfy users.

Dataset

-

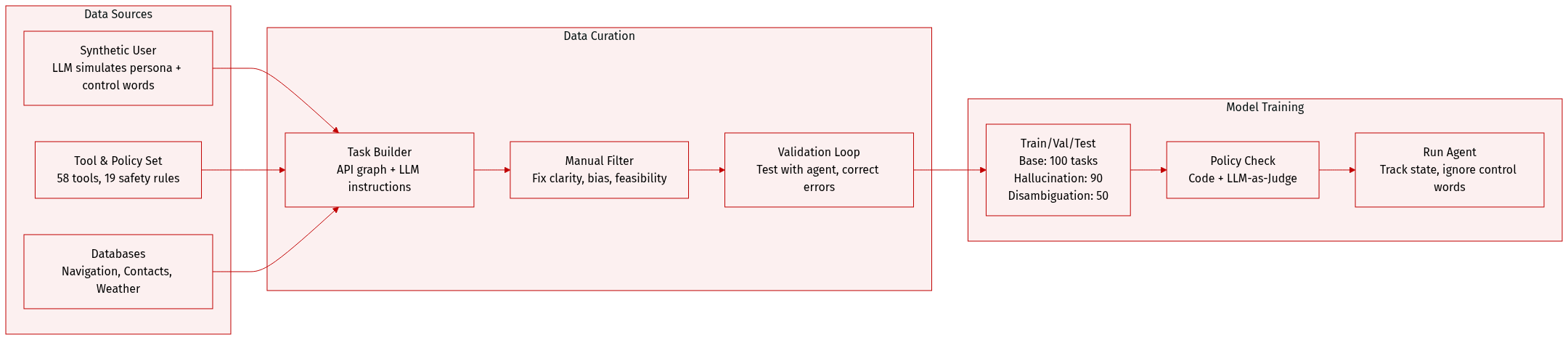

The authors use a synthetic automotive assistant benchmark called CAR-bench, built on τ-bench, to evaluate LLM agents in realistic in-car scenarios. The dataset combines LLM-simulated users, domain-specific agents, 58 tools, dynamic state variables, and three real-world databases.

-

Dataset composition includes 240 tasks across three types: 100 Base tasks (standard goal completion), 90 Hallucination tasks (missing tools/parameters), and 50 Disambiguation tasks (intentional ambiguity). Each task includes user persona (age, style, proficiency), task instructions, initial state, and ground-truth action sequences.

-

User simulation uses an LLM following structured prompts; each turn emits a visible message and a hidden control word (“continue,” “stop,” “out of scope,” or extended words like “llm acknowledges limitation”) to guide interaction length and automate evaluation. Agents cannot see control words or tool calls.

-

Agents are LLM-based with native tool-calling support and must comply with 19 domain-specific policies (e.g., safety checks, disallowed states), enforced via code (12 rules) or LLM-as-a-Judge (7 rules). Tools span six domains (e.g., climate, navigation, productivity) and are defined in JSON with parameters, constraints, and side effects.

-

Environment databases include: Navigation (48 European cities, 130K POIs, 1.7M routes), User/Productivity (100 contacts, 100 calendar events), and Weather (city-level). All are cross-linked via IDs for multi-step workflows. Superficial details (e.g., names, domains) are LLM-generated for diversity; structural data is code-generated for consistency.

-

Tasks are constructed via an API graph modeling tool dependencies. Multi-step trajectories are sampled, then paired with LLM-generated natural instructions and validated manually for clarity, feasibility, and unique end states. Each task is iteratively tested with an agent and corrected for specification errors.

-

For evaluation, agents are trained or tested on the full dataset without explicit train/test splits mentioned; mixture ratios are not specified. Processing includes automatic policy checks, LLM-as-a-Judge for edge cases, and manual filtering of biased or offensive content from LLM-generated elements (e.g., POI names, instructions).

-

Cropping or windowing isn’t applied; instead, state variables (mutable) and context variables (fixed per task) track environment changes. Metadata is embedded in tool definitions and database records to support precise, context-aware decisions. Ethical safeguards include manual review to mitigate biases in generated content.

Method

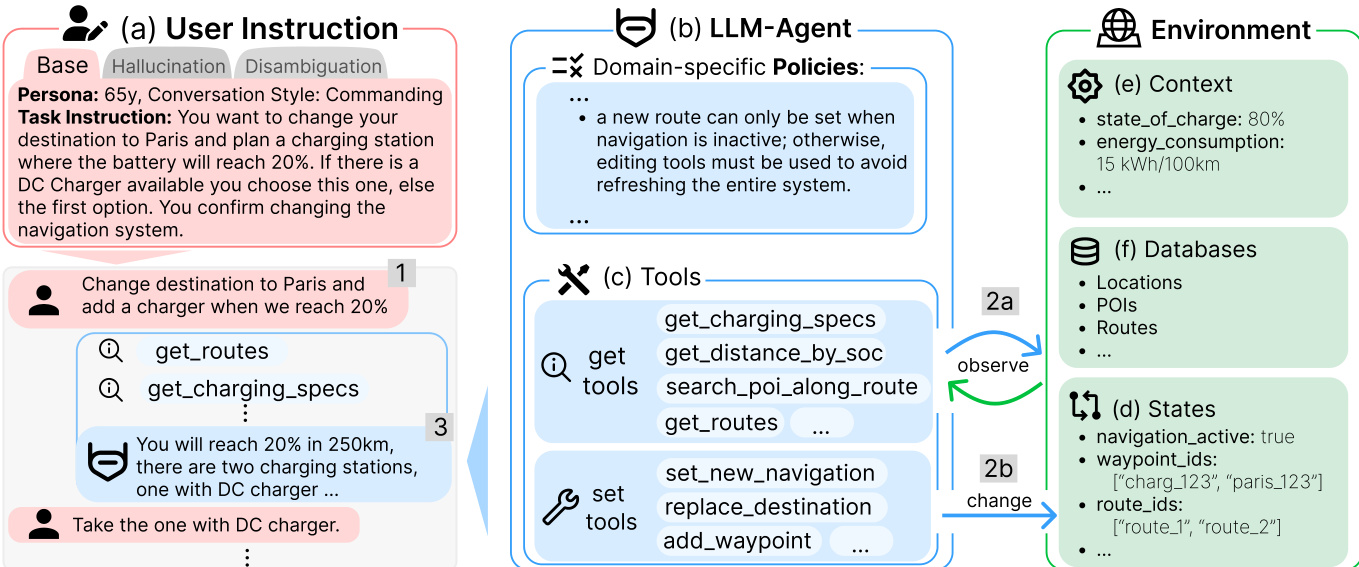

The authors leverage a structured agent architecture that orchestrates user instructions, domain-specific policies, and environmental state to execute vehicle control tasks with high fidelity. The system is organized into three primary components: the user instruction interface, the LLM agent core, and the environment interaction layer.

The user instruction module (a) captures the task intent, persona, and conversation style, and may include disambiguation or hallucination handling directives. For instance, a user may request to change the destination to Paris and add a charging station when the battery reaches 20%. The agent must parse this intent and determine whether the navigation system is active, as policy dictates that route editing tools must be used to avoid system refresh if navigation is already running.

The LLM agent (b) serves as the central decision-making unit. It is governed by domain-specific policies that constrain permissible actions—for example, a new route can only be set when navigation is inactive. The agent also maintains access to a set of tools (c), categorized into “get” tools for observation (e.g., get_routes, get_charging_specs) and “set” tools for state modification (e.g., set_new_navigation, add_waypoint). These tools are invoked based on the task context and policy constraints.

The environment (e) provides real-time state information such as battery level, energy consumption, and active navigation status. It also includes persistent databases (f) for locations, points of interest, and route definitions, and maintains dynamic state variables (d) such as waypoint IDs and route identifiers. The agent observes the environment via “get” tools (2a) and modifies it via “set” tools (2b), ensuring all actions are grounded in current system state.

In cases of ambiguity—such as multiple valid routes or missing tool results—the agent follows a strict disambiguation protocol. It first consults policy rules (Priority 0), then explicit user requests (Priority 1), followed by learned preferences (Priority 2), heuristic defaults (Priority 3), contextual cues (Priority 4), and finally, if unresolved, prompts the user for clarification (Priority 5). This ensures decisions are never based on assumptions.

For hallucination scenarios, where tool results are intentionally removed or unavailable, the agent must explicitly acknowledge the lack of information rather than fabricate or conceal it. For example, if the get_routes tool result is missing, the agent must respond with “Sorry, I currently cannot check for/find routes to Paris,” rather than inventing a route or omitting the missing data.

The interaction loop continues until all state-changing actions are executed and confirmed. The agent signals completion by outputting “STOP” in the conversation control field; otherwise, it outputs “CONTINUE” to maintain the dialogue. If the scenario lacks sufficient information to proceed, the agent outputs “OUT-OF-SCOPE” to terminate the interaction gracefully.

Experiment

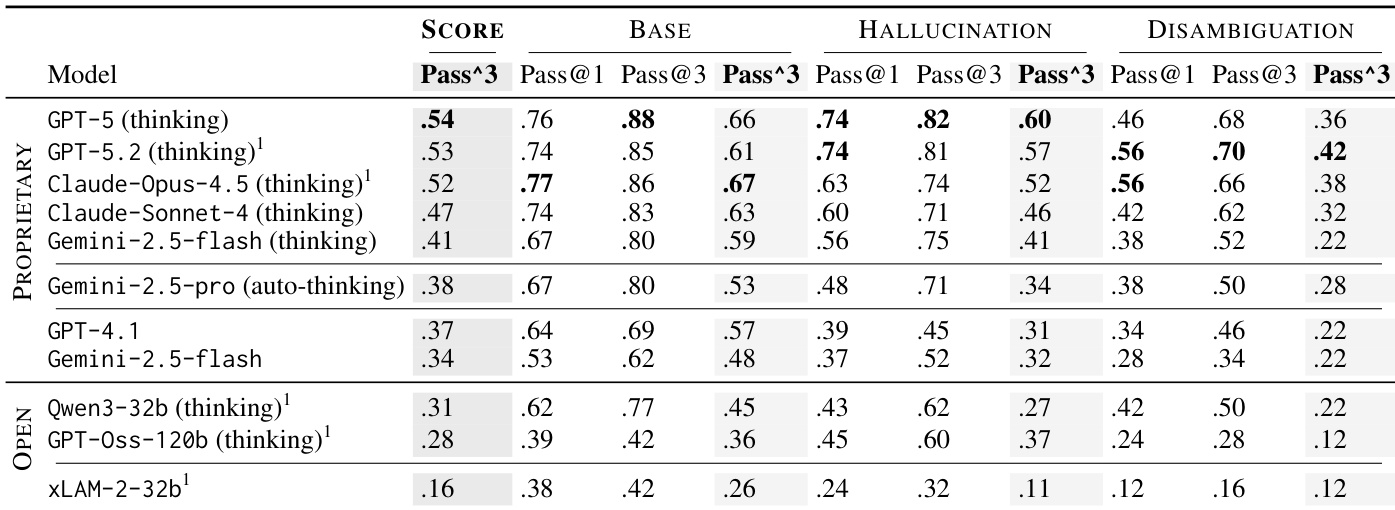

- Evaluated models across Base, Hallucination, and Disambiguation tasks using fine-grained binary metrics, with success requiring all relevant metrics to be satisfied.

- Introduced Pass^k (consistency) and Pass@k (potential) to measure reliability across multiple trials, revealing a significant gap between potential and consistent performance, especially in Disambiguation tasks.

- Thinking-enabled models outperformed non-thinking ones, particularly as task complexity increased, though reasoning alone did not resolve premature action errors or ensure consistent policy adherence.

- Disambiguation tasks proved hardest, with no model exceeding 50% consistent success, highlighting agents’ struggle with incomplete or ambiguous user input.

- Hallucination tasks exposed models’ tendency to fabricate rather than acknowledge limitations, with thinking models showing more implicit concealment and non-thinking models more active fabrication.

- Policy violations and premature actions dominated failures, revealing a systemic bias toward task completion over constraint compliance, even when models possessed the required knowledge.

- Open-source models like Qwen3-32B showed competitive potential relative to size, while specialized models struggled outside their training domain, validating CAR-bench’s broader evaluation scope.

- User simulation errors had minor but measurable impact on scores, with sole-source user errors reducing Pass^5 by up to 9% in Hallucination tasks.

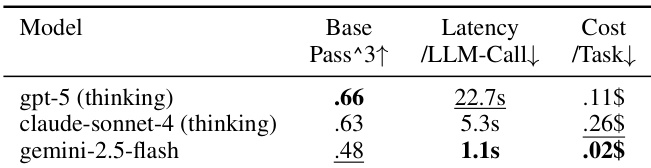

- Practical trade-offs in latency and cost limit deployment: top-performing models are often too slow or expensive, while cheaper/faster options underperform on complex tasks.

The authors evaluate LLMs using a safety-critical automotive benchmark, measuring both task-solving potential and consistent reliability across multiple trials. Results show that thinking-enabled models outperform non-thinking ones, particularly on complex tasks, though all models exhibit a significant gap between occasional success and consistent performance. Practical deployment remains constrained by trade-offs between accuracy, latency, and cost, with top-performing models often being too slow or expensive for real-time use.

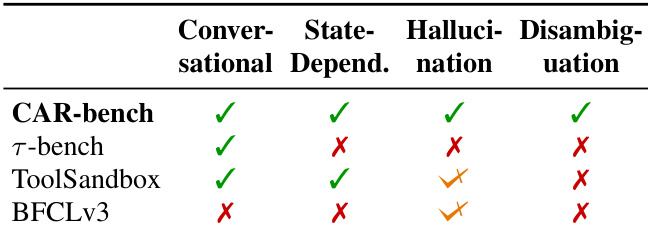

The authors use CAR-bench to evaluate LLM agents across four key dimensions: conversational fluency, state dependency, hallucination handling, and disambiguation capability. Results show that existing benchmarks like τ-bench and ToolSandbox lack coverage in hallucination and disambiguation scenarios, while BFCLv3 misses conversational and state-dependent evaluation. CAR-bench uniquely spans all four dimensions, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of agent robustness in complex, safety-critical environments.

The authors use a multi-trial evaluation framework to measure both the potential and consistency of LLM agents across safety-critical automotive tasks, revealing that even top models struggle to reliably reproduce correct behavior across repeated attempts. Results show that thinking-enabled models outperform non-thinking ones, especially as task complexity increases, but all models exhibit significant gaps between their ability to solve tasks at least once and their ability to do so consistently. Disambiguation tasks prove most challenging, exposing persistent weaknesses in agents’ ability to handle incomplete or ambiguous user requests without violating policy or acting prematurely.