Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

STEM : Augmenter l'échelle des Transformers grâce à des modules d'embedding

STEM : Augmenter l'échelle des Transformers grâce à des modules d'embedding

Ranajoy Sadhukhan Sheng Cao Harry Dong Changsheng Zhao Attiano Purpura-Pontoniere Yuandong Tian Zechun Liu Beidi Chen

Résumé

La sparsité fine promet une capacité paramétrique accrue sans augmentation proportionnelle du coût calculatoire par jeton, mais souffre souvent d’instabilité d’entraînement, de déséquilibre de charge et de surcharge de communication. Nous introduisons STEM (Scaling Transformers with Embedding Modules), une approche statique et indexée par jeton, qui remplace la projection ascendante du FFN (Feed-Forward Network) par une recherche dans une table d’embeddings locale à la couche, tout en maintenant les opérations de porte et de projection descendante denses. Cette approche élimine le routage en temps réel, permet un transfert vers le CPU avec préchargement asynchrone, et découple la capacité à la fois du nombre de FLOPs par jeton et de la communication entre dispositifs. Expérimentalement, STEM s’entraîne de manière stable, même sous une sparsité extrême. Il améliore les performances sur les tâches descendantes par rapport aux modèles denses, tout en réduisant les FLOPs par jeton et les accès aux paramètres (en éliminant approximativement un tiers des paramètres du FFN). STEM apprend des espaces d’embeddings présentant un large écart angulaire, ce qui renforce sa capacité de stockage des connaissances. Plus intéressant encore, cette capacité accrue de stockage des connaissances se traduit par une meilleure interprétabilité. La nature indexée par jeton des embeddings de STEM permet des méthodes simples pour modifier ou injecter des connaissances de manière interprétable, sans intervention sur le texte d’entrée ni calcul supplémentaire. En outre, STEM améliore les performances sur les contextes longs : à mesure que la longueur de la séquence augmente, un plus grand nombre de paramètres distincts sont activés, ce qui permet une augmentation pratique de la capacité au moment du test. Sur des modèles de tailles 350M et 1B, STEM permet des gains d’exactitude allant jusqu’à ~3 à 4 % en général, avec des améliorations marquées sur des benchmarks exigeants en connaissances et raisonnement (ARC-Challenge, OpenBookQA, GSM8K, MMLU). Globalement, STEM constitue une méthode efficace pour échelonner la mémoire paramétrique tout en offrant une meilleure interprétabilité, une stabilité d’entraînement améliorée et une efficacité accrue.

One-sentence Summary

Carnegie Mellon University and Meta AI introduce STEM, a static, token-indexed sparse architecture that replaces the FFN up-projection with layer-local embedding lookup, enabling stable training, reduced per-token FLOPs and parameter access by ~one-third, and improved long-context performance through scalable parameter activation. By decoupling capacity from compute and communication, STEM supports CPU offload with asynchronous prefetching and achieves higher knowledge storage capacity via embeddings with large angular spread, while offering interpretable, edit-friendly knowledge injection without modifying input text—outperforming dense baselines by up to ~3–4% on knowledge and reasoning benchmarks.

Key Contributions

-

STEM addresses the challenge of scaling parametric capacity in Transformers without increasing per-token compute by replacing the FFN up-projection with a static, token-indexed embedding lookup, eliminating runtime routing and enabling efficient CPU offload with asynchronous prefetching while maintaining dense gate and down-projection layers.

-

The method achieves stable training under extreme sparsity and improves downstream performance on knowledge and reasoning benchmarks (e.g., ARC-Challenge, GSM8K, MMLU) by up to ~3-4% over dense baselines, while reducing per-token FLOPs and parameter accesses by roughly one-third through a learned embedding space with large angular spread that enhances knowledge storage.

-

STEM’s token-indexed embedding design enables interpretable knowledge editing and injection without modifying input text or adding computation, and its capacity scales practically with sequence length as more distinct parameters are activated, offering improved long-context performance and system efficiency compared to MoE and PKM approaches.

Introduction

The authors leverage a static, token-indexed embedding module to scale Transformers efficiently, replacing the feed-forward network's up-projection with a layer-local lookup while keeping the gate and down-projection dense. This design enables significant reductions in per-token FLOPs and parameter accesses—eliminating roughly one-third of FFN parameters—without increasing cross-device communication or runtime routing overhead. Unlike prior sparse methods such as MoE, which rely on dynamic routing and suffer from training instability and load imbalance, or PKM models that face high inference lookup costs and under-training issues, STEM achieves stable training at extreme sparsity levels. Its key innovation lies in decoupling parametric capacity from compute and communication, enabling CPU offload with asynchronous prefetching and scalable long-context performance. The learned embedding spaces exhibit large angular spread, enhancing knowledge storage and interpretability, allowing direct knowledge editing and injection without modifying input text or adding computation. STEM delivers up to 3–4% accuracy gains on knowledge and reasoning benchmarks across 350M and 1B models, offering a robust, efficient, and interpretable path to scaling parametric memory in large language models.

Dataset

- The dataset is composed of multiple sources: OLMo-MIX-1124 (3.9T tokens), a mixture of DCLM and Dolma 1.7; NEMOTRON-CC-MATH-v1 (math-focused); and NEMOTRON-PRETRAINING-CODE-v1 (code-focused).

- For pretraining, the authors subsample 1T tokens from OLMo-MIX-1124.

- During mid-training, the data mix consists of 65% OLMo-MIX-1124, 5% NEMOTRON-CC-MATH-v1, and 30% NEMOTRON-PRETRAINING-CODE-v1.

- For context-length extension, the authors use PROLONG-DATA-64K, which is 63% long-context and 37% short-context, with sequences packed up to 32,768 tokens using cross-document attention masking.

- The data is processed with no explicit cropping, but sequences are packed to fit the model’s maximum context length.

- Metadata for long-context evaluation is constructed to support the Needle-in-a-Haystack benchmark, which tests retrieval in extended contexts.

- The authors use the pretraining data to train 350M models on 100 billion tokens and 1B models on 1 trillion tokens, with mid-training using 100 billion tokens and context extension using 20 billion tokens.

- Training employs AdamW with a cosine learning rate schedule, 10% warmup, and a minimum LR of 0.1 times the peak.

- The model architecture uses separate input embeddings and language model heads, with one-third of FFN layers replaced by sparse alternatives (STEM or Hash layer MoE), maintaining comparable activated FLOPs to the dense baseline.

Method

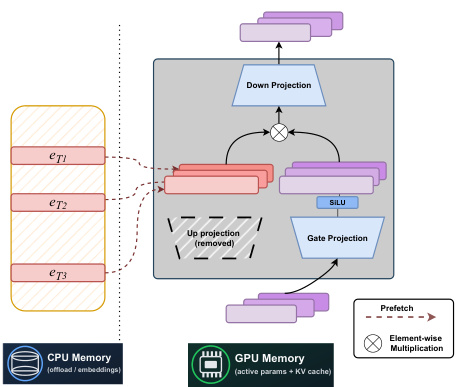

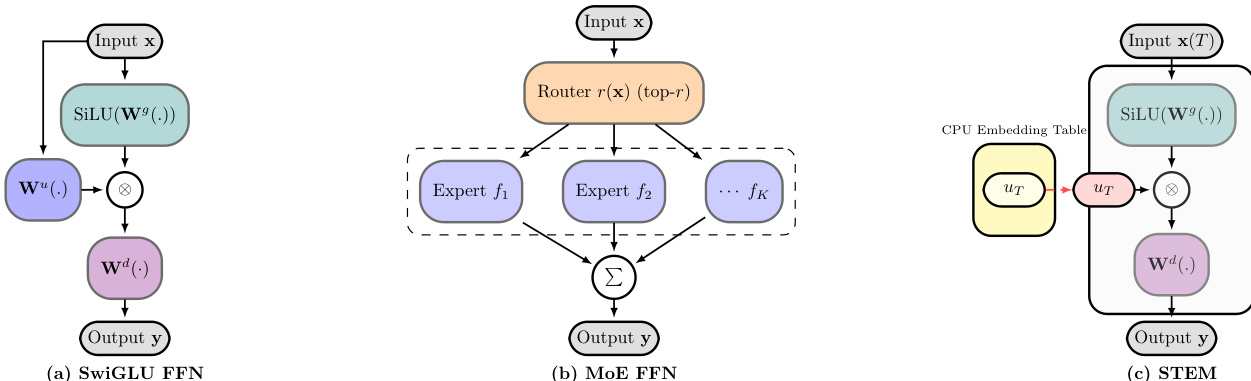

The authors leverage a modified feed-forward network (FFN) architecture within a decoder-only transformer, building upon the SwiGLU activation function and the key-value memory perspective of FFNs to introduce the STEM (Static Token-Embedded Mixture) model. The standard SwiGLU FFN, as shown in Figure (a), processes an input hidden state xℓ through a gate projection Wℓg, an up projection Wℓu, and a down projection Wℓd. The transformation is defined as yℓ=Wℓd(SiLU(Wℓgxℓ)⊙(Wℓuxℓ)), where the up projection generates an address vector for retrieving information from the down projection, and the gate projection provides context-dependent modulation.

The STEM design, illustrated in Figure (c), fundamentally rethinks this process by replacing the up projection with a token-indexed embedding lookup. For a given layer ℓ and input token t, the model accesses a per-layer embedding table Uℓ∈RV×dff to retrieve the vector Uℓ[t]. The output is then computed as yℓ=Wℓ(d)(SiLU(Wℓ(g)xℓ)⊙Uℓ[t]). This design choice is motivated by the key-value memory view of FFNs, where the up projection acts as a key for content retrieval, and the gate projection acts as a context-dependent modulator. By replacing the up projection with a static, token-specific embedding, STEM decouples the parametric capacity from the per-token computation, enabling a more efficient and interpretable architecture.

The system architecture, as depicted in the figure, highlights the key components of the STEM model. The model's forward pass begins with the input hidden state xℓ, which is processed by the gate projection Wℓg and passed through the SiLU activation function. Simultaneously, the token t is used to index the CPU memory, where the corresponding STEM embedding Uℓ[t] is prefetched. This embedding is then elementwise multiplied with the output of the SiLU function. The result is passed to the down projection Wℓd to produce the final output yℓ. The figure also shows that the STEM embeddings are stored in CPU memory, which allows for offloading and asynchronous prefetching, reducing the GPU memory footprint and communication overhead. The down projection and gate projection remain in GPU memory as active parameters, while the STEM embeddings are stored in CPU memory, enabling efficient memory management.

The comparison of architectures in Figure (a), (b), and (c) illustrates the evolution from a standard SwiGLU FFN to a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) FFN and finally to the STEM FFN. The standard SwiGLU FFN (a) uses a single, dense up projection. The MoE FFN (b) replaces this with multiple expert FFNs and a router that selects a subset of experts based on the input. In contrast, the STEM FFN (c) replaces the up projection with a token-indexed embedding lookup, which is stored in CPU memory. This design avoids the need for a trainable router and the associated communication overhead of expert parallelism, making it more efficient and scalable. The STEM architecture also allows for better interpretability, as the embeddings are directly tied to specific tokens and can be used for knowledge editing.

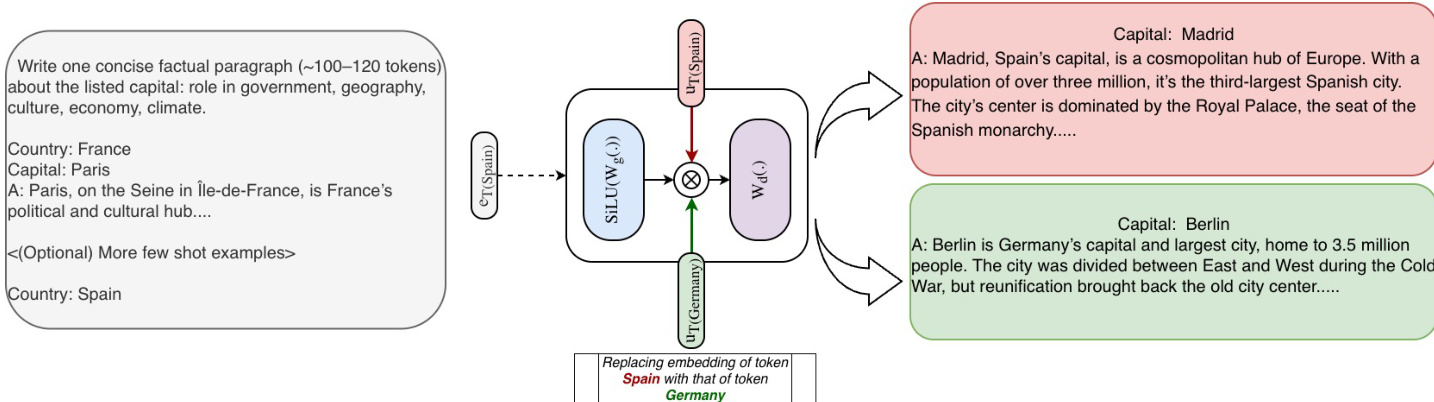

The knowledge editing demonstration in the figure shows how STEM embeddings can be used to modify the model's output by changing the embeddings for specific tokens. The prompt "Country: Spain" is used to generate a paragraph about Madrid. By replacing the STEM embedding for the token "Spain" with the embedding for "Germany", the model generates a paragraph about Berlin instead. This demonstrates the ability of STEM to perform precise, token-indexed knowledge editing, which is a direct consequence of the clear mapping between the embeddings and the tokens. The figure also shows that this editing can be done even when the source and target entities have different tokenization lengths, using strategies such as padding, copying, or subset selection. This ability to manipulate the model's knowledge in a targeted and interpretable way is a key advantage of the STEM architecture.

Experiment

- STEM replaces the up-projection in gated FFNs with token-indexed embeddings, achieving stable training without loss spikes, unlike fine-grained MoE models.

- On ARC-Challenge and OpenBookQA, STEM outperforms the dense baseline by ~9–10% and shows improved performance with more STEM layers.

- STEM improves long-context inference: on Needle-in-a-Haystack, it achieves 13% higher accuracy than the dense baseline at 32k context length.

- STEM reduces per-token FLOPs and parameter accesses by up to one-third, with training ROI improvements of 1.08x (1/3 layers), 1.20x (1/2 layers), and 1.33x (full layers) over the dense baseline.

- STEM exhibits large angular spread in embedding space (low pairwise cosine similarity), enhancing information storage capacity and reducing representational interference.

- STEM enables interpretable, reversible knowledge editing: swapping token-specific embeddings shifts factual predictions (e.g., Madrid → Berlin) without changing input.

- STEM outperforms the dense baseline on GSM8K, MMLU, BBH, MuSR, and LongBench multi-hop/code-understanding tasks, demonstrating superior reasoning and knowledge retrieval.

- STEM maintains efficiency across batch sizes, with sustained FLOPs and memory access savings due to static, token-indexed sparsity and reduced parameter traffic.

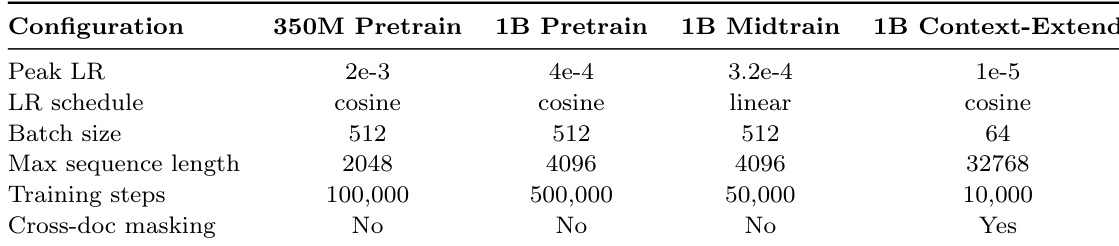

The authors use a consistent learning rate schedule across all configurations, with cosine decay for pretraining and linear decay for midtraining, while adjusting the peak learning rate and batch size to match the computational demands of each setting. Training steps are reduced for midtraining and context-extension tasks, and cross-document masking is enabled only for the context-extension experiment.

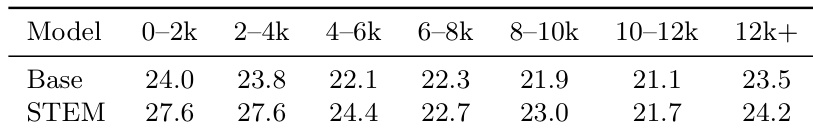

Results show that the STEM model achieves higher performance than the dense baseline across all context lengths, with the largest improvement observed in the 0–2k range, where STEM scores 27.6 compared to the baseline's 24.0. The performance gap narrows at longer contexts, but STEM maintains a consistent advantage, indicating improved long-context capabilities.

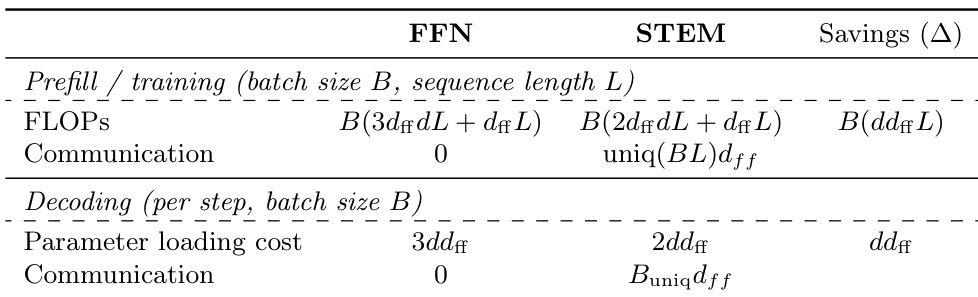

The authors compare the computational and communication costs of standard FFN and STEM architectures during prefill and decoding. For prefill and training, STEM reduces FLOPs by replacing the up-projection with token-indexed embeddings, resulting in a saving of B(dffL) FLOPs. During decoding, STEM reduces parameter loading cost by half and eliminates communication, achieving a saving of ddff per step.

The authors use STEM to replace the up-projection in gated FFNs with token-indexed embeddings, achieving better training stability and improved performance on knowledge-intensive tasks compared to dense and MoE baselines. Results show that STEM consistently outperforms the dense baseline on benchmarks like ARC-Challenge and OpenBookQA, with gains increasing as more FFN layers are replaced, while also reducing per-token FLOPs and parameter accesses.

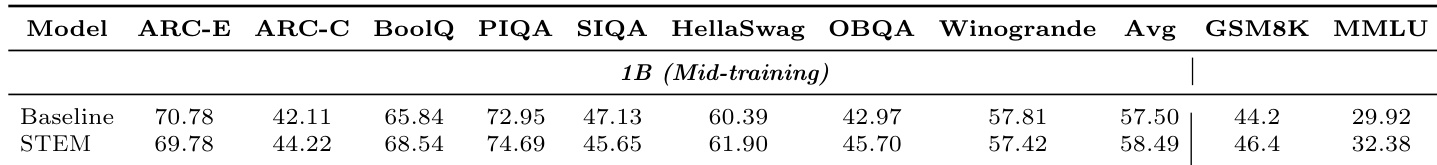

The authors compare the STEM model with a dense baseline on a 1B-scale mid-trained model across multiple downstream tasks. Results show that STEM consistently outperforms the baseline on knowledge-intensive tasks such as ARC-E, PIQA, and OBQA, with improvements of 2.1 to 4.1 points, while achieving comparable or slightly better performance on other tasks. The average score across all evaluated tasks increases from 57.50 to 58.49, indicating a general improvement in model performance.